Research Paper Review: WaveScalar

The paper presents WaveScalar, an alternative to superscalar design, a dataflow ISA and execution model designed for scalable, simple, high-performance processors. It provides traditional memory semantics and can run programs in any language without sacrificing parallelism. WaveCache, a key component of WaveScalar, minimizes long-wire, and high-latency communication by keeping data and computation closer. The paper assesses a simulated implementation across SPEC and Mediabench applications, showing a substantial 2-7 times speed improvement over an aggressively configured superscalar design, with potential for further enhancements.

Paper Summary

The paper highlights that merely scaling up current architectures will not translate into proportionate performance gains. This discrepancy between the needed and the achievable improvements will significantly impact processor designs. Three key issues contribute to this challenge, forming a processor scaling wall: the widening gap between computation and communication speeds; the rising costs of circuit complexity, resulting in longer design times, delays, and more processor bugs; and the declining reliability of circuit technology due to smaller feature sizes and continued scaling of the underlying material characteristics. Specifically, modern superscalar processor designs face scalability limitations due to their reliance on intricate infrastructure like slow broadcast networks, associative searches, complex control logic, and inherently centralized structures —all of which must be precisely designed for reliable operation.

In response to this challenge, various research efforts have explored enhancing the von Neumann model with redundant checking mechanisms, limited dataflow-like execution by exploiting compiler technology, and coarse-grained parallelism. In contrast, the paper introduces WaveScalar, a novel dataflow instruction set and computing model that minimizes communication costs by eliminating long wires and broadcast networks through a decentralized ``token-store” implementation of traditional dataflow architectures and a distributed execution model. WaveScalar efficiently supports traditional von Neumann-style memory semantics, enabling the execution of general-purpose, imperative languages (like C, C++, Fortran, or Java) - a longstanding challenge for dataflow machine researchers. By resolving the memory ordering problem without a von Neumann-like model, WaveScalar enables the creation of a decentralized dataflow processor, eliminating large hardware structures that hinder scalability in superscalar designs. Unlike previous attempts such as TRIPS and Raw, which extended the von Neumann paradigm but still relied on a program counter, WaveScalar completely abandons this approach. Instead, it’s designed for cache-only computing systems where processing nodes replace the central processor and instruction cache. WaveScalar instructions execute in memory and transmit results directly to dependents via the WaveCache, a distributed instruction cache. The WaveCache optimizes instruction placement based on dataflow patterns, enhancing performance. The paper introduces the WaveScalar ISA and a WaveCache architecture, highlighting four key contributions: providing total load/store ordering memory semantics for efficient execution of imperative programs, introducing an efficient distributed dataflow tag management scheme, presenting the WaveCache architecture, and offering a performance comparison with aggressive superscalar designs.

WaveScalar

The original motivation behind WaveScalar was to construct a decentralized superscalar processor core. Initially, the researchers scrutinized each element of a superscalar architecture and endeavored to devise new decentralized hardware algorithms for them. However, they encountered a significant hurdle in decentralizing instruction fetch, primarily because of its reliance on a single program counter. To address this challenge, they opted to change the processor’s fetch method from being program counter-driven to data-driven. Consequently, their ``superscalar” processor swiftly evolved into a compact dataflow machine. This transformation prompted them to tackle the task of creating a fully decentralized dataflow machine, ultimately leading to the development of WaveScalar and the WaveCache. Dataflow computers operate based on data availability, with values labeled by tags and stored in specialized memory until required. Historically, dataflow technology faced obstacles in constructing high-performance machines and efficiently providing total load/store ordering, as mandated by most programming languages. However, technological advancements have rendered these challenges surmountable, making dataflow a viable computing technology for parallel processing.

The proposed approach, WaveScalar, introduces a novel method for dataflow computing that tackles the challenges discussed. In this concept, a WaveScalar binary represents the dataflow graph of an executable and is stored in memory as a collection of intelligent instruction words. Each instruction word is associated with a dedicated functional unit. Due to practical limitations, an intelligent instruction cache known as the WaveCache holds the current set of instructions and executes them in place. WaveScalar executables incorporate a dataflow graph encoding alongside standard RISC-like instructions, including special instructions for controlling flow.

To handle control dependencies in dataflow machines, WaveScalar employs two main solutions: conditional selector (\(\phi\)) instructions and conditional split (\(\phi^{-1}\)) instructions. \(\phi\) instructions act like conditional moves, providing predication while increasing parallelism. However, they discard one input, making them somewhat inefficient. In contrast, \(\phi^{-1}\) instructions direct data values based on a selector, resembling traditional branch instructions and essential for implementing loops. While the WaveScalar ISA supports both instruction types, the current toolchain only supports \(\phi^{-1}\) instructions.

WaveScalar introduces the concept of waves, which break down the control flow graph of an application into manageable segments. These waves execute one at a time and feature partially ordered instructions with a single entrance point, allowing for efficient memory ordering. Waves simplify parallelism extraction compared to hyper-blocks and offer advantages in loop unrolling.

One significant aspect of WaveScalar is its handling of wave numbers to manage multiple instances of data simultaneously. Each data value carries a tag, and wave numbers differentiate dynamic waves. The WAVE-ADVANCE instruction manages wave numbers by incrementing them for each input value, enabling distributed wave-number management under software control.

Moreover, WaveScalar supports indirect jumps, crucial for modern systems utilizing object linking and shared libraries. The INDIRECT-SEND instruction facilitates this functionality by sending data values to consumer instructions based on addresses and offsets, enabling function calls and returns without compile-time knowledge of function addresses.

Memory ordering ensures that operations on memory occur in the correct sequence, crucial for program correctness. Traditional imperative languages rely on a model called “total load-store ordering.” WaveScalar extends this concept to dataflow computing through wave-ordered memory. In wave-ordered memory, each memory operation is labeled with its position in a wave and its relationships with other memory operations within the same wave, based on the control flow graph. The WaveScalar compiler assigns a unique sequence number to each memory operation within a wave, ensuring sequential ordering. Links between memory operations encode the wave’s control flow graph structure. When executing, memory operations transmit their link, wave number, address, and data to the memory system, ensuring correct sequencing. The memory system uses this information to assemble loads and stores accurately. Wave-ordered memory allows WaveScalar to efficiently execute programs written in conventional languages by separating memory ordering from control flow. It simplifies memory management for processing elements and enables concise representation of program paths. This approach has potential for speculative memory systems and further enhancements for exploiting memory parallelism, which are areas of ongoing research.

The WaveCache: a WaveScalar processor

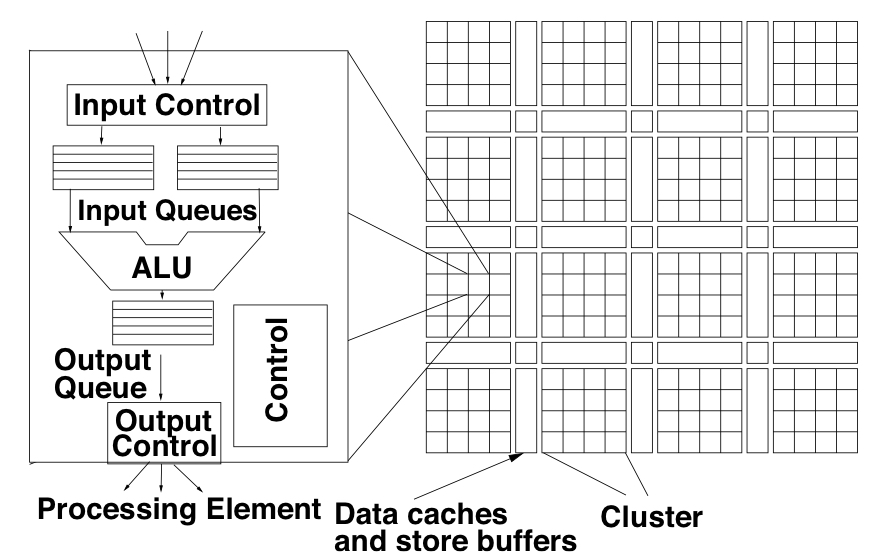

In this section, a design for a compact WaveCache that could be developed within the next 5-10 years to execute WaveScalar binaries is presented (refer to Figure 1). The WaveCache comprises approximately 2K processing elements (PEs) organized into clusters of 16, each containing logic for controlling instruction placement and execution, input and output queues for instruction operands, communication logic, and a functional unit. With buffering and storage for 8 instructions per PE, the WaveCache has a total capacity of 16 thousand instructions, equivalent to a 64KB instruction cache in a modern RISC machine. Input queues require minimal ports and entries per instruction, indexed relative to the current wave. Additionally, the WaveCache features a store buffer and traditional L1 data cache for every 4 clusters of PEs, accessing DRAM via a unified L2 cache. Inter-PE communication within clusters occurs through shared buses, while communication between clusters is facilitated by a dynamically routed on-chip network. Effective instruction placement is essential for performance optimization, as communication latency depends on it. The WaveCache design incorporates a distributed store buffer scheme, with each set of 4 processing element clusters sharing a store buffer among 64 functional units. Two proposed solutions address the assignment of store buffers to waves, ensuring efficient memory management during execution.

Results

In this section, the performance of the WaveScalar ISA and the WaveCache is examined. Seven aspects of execution are investigated: the WaveCache’s performance compared to a superscalar and the TRIPS processor; the overhead due to WaveScalar instructions; the effects of cluster size, cache replacement, and input queue size on performance; and the potential effectiveness of control and memory speculation. These results illustrate the potential for good WaveScalar performance and identify areas for further investigation.

The baseline WaveCache configuration described in the previous section is used, with 16 processing elements per cluster, unbounded input queues, and perfect L1 data caches. Instructions are statically placed into clusters using a simple greedy strategy. To achieve better results in the future, a dynamic placement algorithm is expected to be employed. Additionally, an optimization is modeled that allows store addresses to be sent to the memory system as soon as they are available.

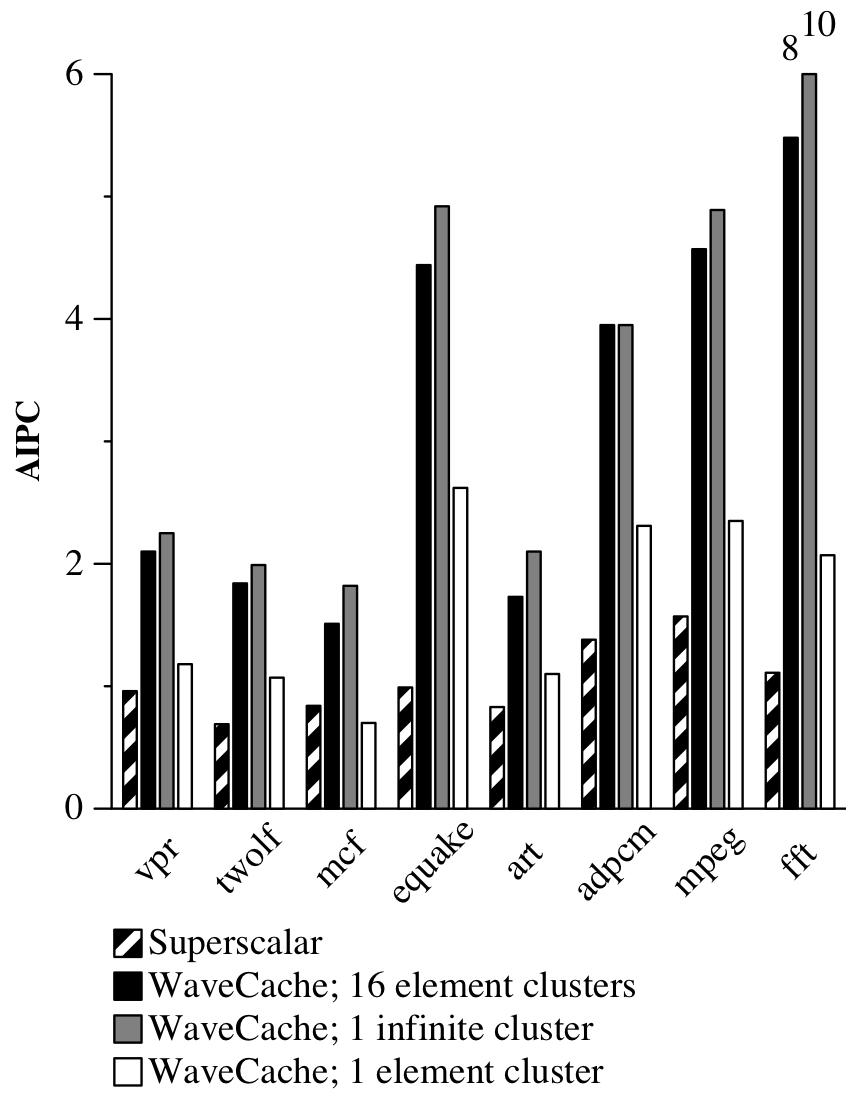

For comparison, a high-performance superscalar machine is used, featuring 15 pipeline stages, a 16-wide out-of-order processing core, 1024 physical registers, and a 1024-entry issue window. Benchmarks from SPECint2000, SPECfp2000, and mediabench are compiled using the Compaq cc compiler, and a custom binary rewriting tool converts Alpha binaries into the WaveScalar instruction set. The results are reported in terms of Alpha-equivalent instructions per cycle (AIPC).

The WaveCache, with 16 processing elements per cluster, outperforms the superscalar by an average factor of 3.1 (Figure 2). For highly loop-parallel applications like equake and fft, the WaveCache is 4-7 times faster than the superscalar. This substantial improvement is attributed to WaveCache’s avoidance of false control dependencies, which artificially constrain ILP. Overall, the WaveCache’s performance is a conservative estimate of its real potential, as further optimization could enhance its efficiency.

Comparing the WaveCache to the TRIPS processor, a recent VLIW-dataflow hybrid offers insights. TRIPS organizes VLIW instructions into vertical hyperblocks, explicitly describing dependencies. Instructions within a hyperblock execute according to dataflow rules, with communication between hyperblocks through a register file. However, TRIPS retains a von Neumann architecture at its core, with the program counter dictating hyperblock sequence execution.

In their memory speculation study and recent TRIPS work, both assume a perfect memory system with memory disambiguation. Despite using different compilers, a cross-study comparison of IPC is informative. The WaveCache allows back-to-back instruction execution, possibly leading to longer cycles, while TRIPS incurs no delay for bypassing the same functional unit and minimal delay for accessing remote functional units.

For shared applications, the WaveCache outperforms the baseline TRIPS architecture by 2.5 times in IPC. However, a modified TRIPS design with enhanced bypassing narrows the performance gap to 90%. Notably, TRIPS excels in certain applications due to potentially better instruction placement. Yet, WaveCache generally outperforms TRIPS due to its pure dataflow execution model and ability to execute waves instead of smaller hyperblocks. This suggests the memory ordering strategy introduced in this paper could benefit TRIPS-like processors.

Static instruction count overhead varies from 20% to 140%, but its impact on performance is minimal. Most added instructions execute in parallel, with their latency only marginally affecting performance.

Efficient data communication and high performance without long wires are goals of the WaveCache. Cluster size significantly impacts performance, with 16-processing-element clusters achieving 90% of the infinite case’s performance. These clusters balance dataflow locality well, with minimal inter-cluster communication. Singleton clusters reduce performance by 51%, but even then, a single-element cluster WaveCache outperforms a 15-stage superscalar by an average of 72%, while also reducing wire length and potentially increasing clock rate.

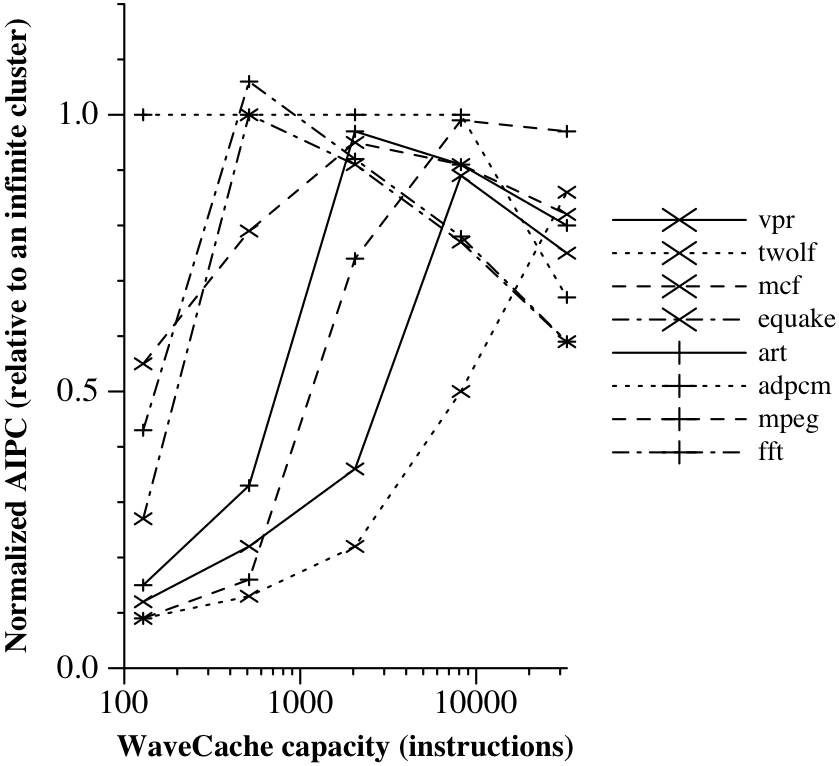

To analyze the impact of capacity on WaveCache performance, cache capacity is varied from a single processing element cluster (128 instructions) to a 16-by-16 array of clusters (32K instructions). Each instruction is statically assigned to a cluster, and replacement is done per-cluster based on an LRU algorithm. Assuming 32 cycles to read the instruction state from memory and between 1 to 24 cycles to transmit data across the cache, depending on cache size.

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of cache misses on performance. With the exception of adpcm, which has a low miss rate, performance increases as the miss rate decreases. However, for mcf, equake, fft, and mpeg, performance decreases as cache size increases beyond a certain point. Spreading all instructions across a large WaveCache becomes inefficient, as it’s better to collect the working set of instructions in a smaller physical space to reduce communication latency and improve performance. The ability to exploit dynamic instruction placement sets the WaveCache apart, allowing it to aggressively exploit dataflow locality for higher performance. Dynamic instruction placement and optimization are key priorities for future work.

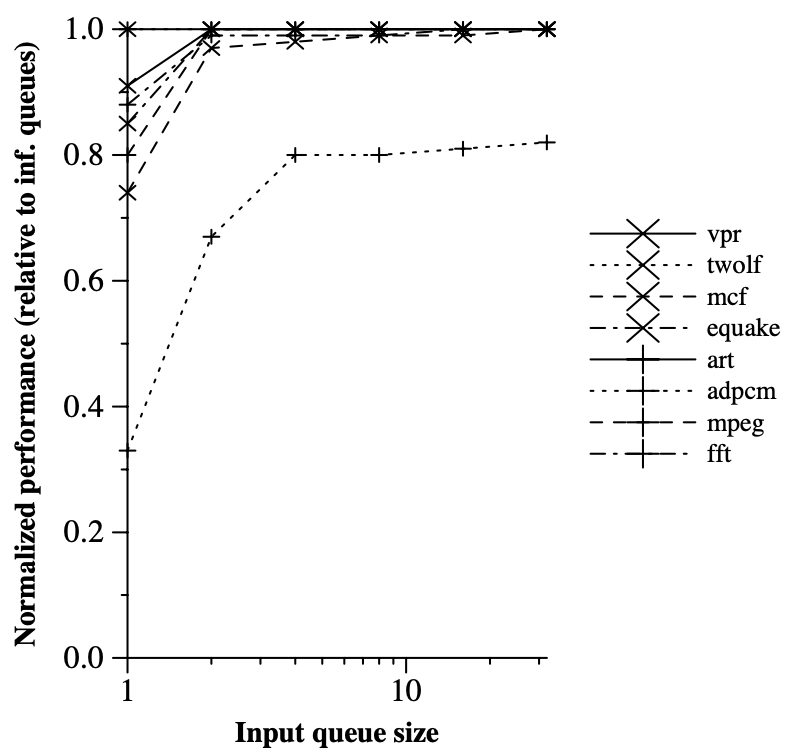

In reality, each instruction in the WaveScalar model has limited storage for buffering input values and performing wave number matching among them. Each input queue in the WaveCache stores overflow values in a dedicated portion of the virtual address space. A simple prefetching mechanism brings values back into the queue as space becomes available. Figure 4 shows that performance is largely unaffected by queue size, except for adpcm, which experiences a 20% slowdown with even 32-entry queues due to the “parallelism explosion” problem with dataflow architectures. Future plans include adding a back pressure mechanism to maintain a small required queue size.

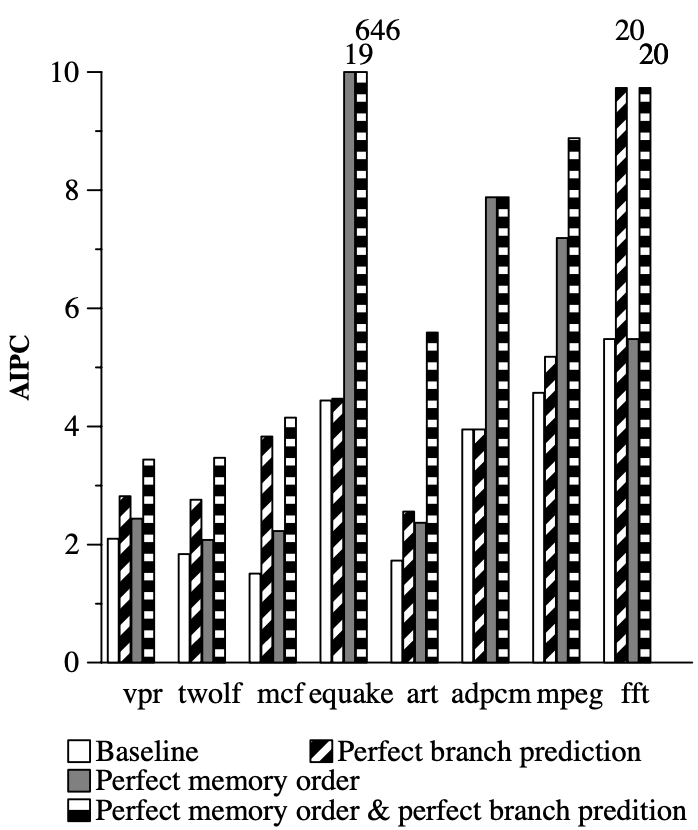

While speculation is necessary for high performance in superscalar designs, the WaveCache can benefit from speculation but doesn’t require it for high performance. Perfect branch prediction increases WaveCache performance by 47% on average, with memory disambiguation providing a substantial boost of 62% (Figure 5). Perfect disambiguation, combined with perfect branch prediction, yields a 340% improvement over the baseline WaveCache. These results demonstrate the potential role of speculation in enhancing WaveCache performance, although it’s not essential for achieving high performance, as with von Neumann processors.

Critical Review

Pros

- Scalability: WaveScalar offers a decentralized approach to superscalar processing, potentially enabling scalable performance improvements by distributing processing elements across a grid-like architecture.

- Dataflow Execution Model: WaveScalar implements a dataflow execution model, which allows instructions to execute as soon as their operands are available, potentially increasing parallelism and overall performance.

- Memory Ordering: WaveScalar introduces wave-ordered memory, which annotates memory operations with information about their location in the control flow graph, enabling efficient memory ordering without relying on traditional control flow mechanisms.

- Performance Potential: Experimental results suggest that WaveScalar could outperform traditional superscalar architectures in certain scenarios, especially for highly parallel applications.

Cons

- Complexity: Implementing and optimizing WaveScalar architecture may require significant effort due to its decentralized nature and the need to manage dataflow execution efficiently.

- Limited Software Ecosystem: Adapting existing software to run efficiently on WaveScalar architecture may be challenging due to differences in the execution model and memory ordering strategy compared to traditional von Neumann architectures.

- Speculation Requirements: While speculation can improve performance in WaveScalar, it adds complexity and may not be necessary for achieving high performance in all scenarios.

Takeaways

- Decentralized Superscalar Approach: WaveScalar proposes a novel decentralized approach to superscalar processing, aiming to achieve scalability and performance improvements by distributing processing elements across a grid-like architecture.

- Dataflow Execution Model: WaveScalar adopts a dataflow execution model, where instructions execute based on data availability rather than traditional control flow mechanisms. This approach potentially increases parallelism and overall performance.

- Wave-Ordered Memory: WaveScalar introduces wave-ordered memory, annotating memory operations with information about their location in the control flow graph to enable efficient memory ordering without relying on traditional control flow mechanisms.

- Performance Potential: Experimental results suggest that WaveScalar has the potential to outperform traditional superscalar architectures, particularly for highly parallel applications. However, achieving this performance may require optimizing software and hardware for the WaveScalar architecture.

- Future Directions: The paper identifies dynamic instruction placement and optimization as key priorities for future work, indicating ongoing efforts to improve the scalability and performance of WaveScalar architecture.

References

- S. Swanson, K. Michelson, A. Schwerin, and M. Oskin, “Wavescalar,” in Proceedings. 36th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2003. MICRO-36., 2003, pp. 291–302.