Research Paper Review: Polymorphous TRIPS Architecture

This paper presents the polymorphous TRIPS architecture, which can be configured for different granularities and types of parallelism. The results indicate significant performance capabilities across all three modes — ILP, TLP, and DLP — highlighting the potential of the polymorphous coarse-grained approach for future microprocessors.

Paper Summary

General-purpose microprocessors have achieved success due to their ability to effectively handle a wide range of tasks. However, there’s a growing trend towards specialized processors tailored to specific applications. Designing processors that excel not only with single-threaded programs but also various forms of concurrency could offer significant benefits in terms of system flexibility and cost reduction.

Unfortunately, current design trends lean towards more specialized processors rather than versatile ones. This trend leads to performance fragility, where application performance fluctuates based on how well it aligns with the processor’s design. This fragility results from the combination of diverse workloads and the prevalence of CMPs with fixed numbers and types of processors.

To address processor fragility, one approach is to integrate heterogeneous processors on a single chip. However, this approach increases hardware complexity and may lead to inefficient resource utilization. An alternative is to incorporate one or more homogeneous processors on a chip, which simplifies hardware design but requires the processors to effectively handle a wide range of applications. This capability to configure hardware for efficient execution across diverse applications is termed architectural polymorphism.

Determining the optimal granularity of processors and memories for polymorphic capabilities is crucial for future chip designs. The architectures with finer granularity, offer high performance for applications with fine-grained parallelism but struggle with general-purpose and serial tasks. On the other end, coarser-grained architectures historically lack the ability to excel in highly parallel, fine-grained applications. Polymorphism offers two competing approaches to bridge this gap.

A synthesis approach employs a fine-grained CMP to exploit regular parallelism and synthesizes multiple processing elements into larger “logical” processors to handle irregular parallelism. In contrast, a partitioning approach implements a coarse-grained CMP in hardware and logically partitions large processors to exploit finer-grained parallelism when needed.

While a polymorphous architecture may not surpass custom hardware tailored for specific applications, it aims to perform well across various application classes with only minor performance degradations compared to specialized solutions.

This paper introduces the polymorphous TRIPS architecture, employing the partitioning approach. It combines coarse-grained polymorphous Grid Processor cores with an adaptive on-chip memory system. The goal is to design cores that are large yet few in number, maximizing single-thread performance while being partitionable to exploit fine-grained parallelism. Results demonstrate that this partitioning approach effectively addresses fragility, achieving high performance for both coarse and fine-grained concurrent applications. However, challenges remain for the synthesis approach in terms of distributed control, interaction latencies, and synchronization overheads.

The TRIPS Architecture

The TRIPS architecture combines large, coarse-grained processing cores for high performance on single-threaded applications with high ILP. It also incorporates polymorphous features that allow the cores to be subdivided for explicitly concurrent applications at various levels of granularity.

Unlike traditional large-core designs with centralized components that are challenging to scale, TRIPS heavily partitions its architecture to avoid large centralized structures and long wire runs. These partitioned computation and memory elements are connected via point-to-point communication channels, which can be optimized by software schedulers.

A key challenge in designing the polymorphous features is finding the right balance in granularity to effectively handle workloads with different levels of ILP, TLP, and DLP. The TRIPS system utilizes coarse-grained polymorphous features, particularly at the level of memory banks and instruction storage, to minimize both software and hardware complexity and configuration overheads.

The TRIPS architecture operates on large blocks of instructions, known as hyperblocks, with a single entry point, no internal loops, and multiple possible exit points. These blocks are statically scheduled by the compiler onto the computational engine to ensure explicit inter-instruction dependencies. In all modes of operation, programs compiled for TRIPS are divided into these blocks, which commit atomically and handle interrupts only at block boundaries. Each block has a fixed set of inputs and potential outputs depending on its exit point. During runtime, the processor fetches a block from memory, loads it into the computational engine, executes it, commits its results if needed, and moves to the next block.

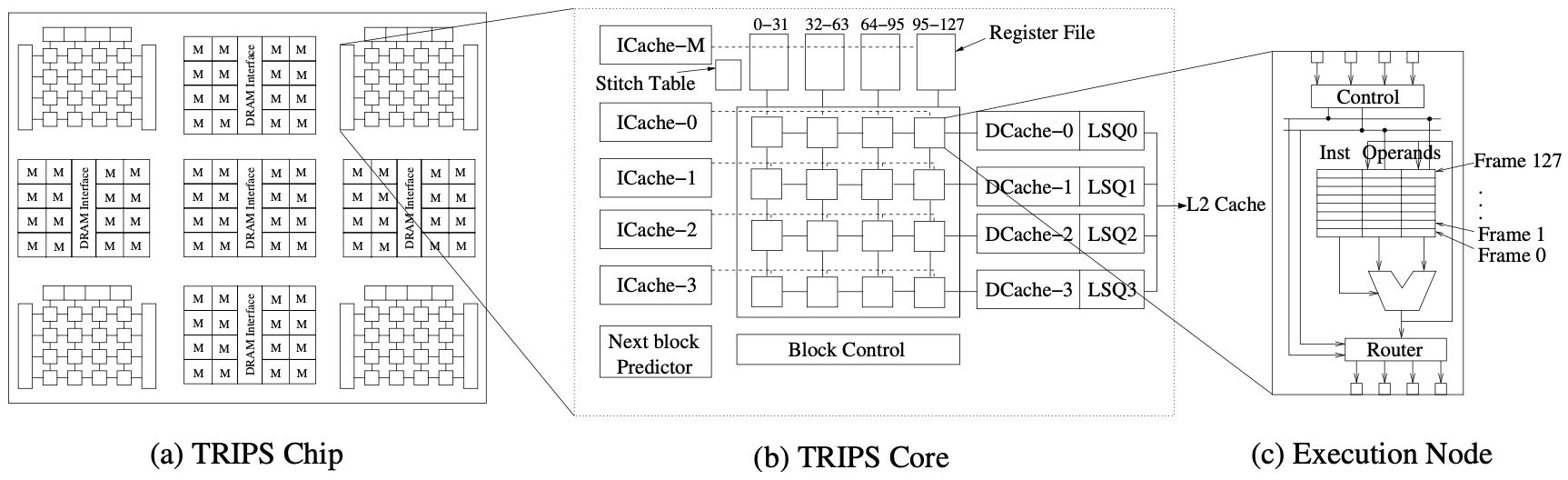

Figure 1(a) depicts the TRIPS architecture intended for a prototype chip. The design is scalable, enabling larger dimensions and higher clock rates due to partitioned structures and short point-to-point wiring connections. The prototype chip will feature four polymorphous 16-wide cores, a network-connected array of 32KB memory tiles, and distributed memory controllers with channels to external memory. It will be fabricated using a 100nm process and is expected to be completed by 2005.

In Figure 1(b), an expanded view of a TRIPS core and the primary memory system is presented. The TRIPS core is part of the Grid Processor family of designs, comprising an array of homogeneous execution nodes, each equipped with an integer ALU, a floating-point unit, reservation stations, and router connections. Each reservation station holds an instruction and two source operands, facilitating execution and result forwarding within the ALU array. Nodes are interconnected with their nearest neighbors, while a routing network enables result delivery to any node in the array.

The architecture includes a banked instruction cache, a banked register file, and level-1 data caches. Block control logic manages block execution sequencing and selection. The backside of the L1 caches connects to secondary memory tiles through a chip-wide two-dimensional interconnection network, offering robust and scalable connectivity with reduced wiring.

Three main types of resources characterize the TRIPS architecture: hardcoded non-polymorphous resources, polymorphous resources configurable for different modes of operation, and resources that are mode-specific and can be disabled when not in use. The polymorphous resources are as follows:

Frame Space

In each execution node, reservation stations with the same index form a physical frame. These frames collectively constitute the frame space, which is managed differently by various modes in TRIPS to support different forms of parallelism efficiently.

Register File Banks

While each execution mode sees a consistent number of architecturally visible registers, the hardware substrate provides additional copies. These extras can be utilized for speculation or multithreading, depending on the mode of operation.

Block Sequencing Controls

These controls determine when a block finishes execution, when it should be removed from the frame space, and which block should be loaded next. Different policies govern these actions to support various modes of operation. For instance, deallocation logic may allow a block to execute multiple times, beneficial for streaming applications. The next block selector can be configured to limit speculation and prioritize between concurrently executing threads, useful for multithreaded parallel programs.

Memory Tiles

TRIPS Memory tiles can act as NUCA-style L2 cache banks, scratchpad memory, or synchronization buffers for producer/consumer communication. The memory tiles closest to each processor feature a special high-bandwidth interface optimized for use as stream register files.

D-morph: Instruction-Level Parallelism

The TRIPS processor’s desktop morph, or D-morph, leverages its polymorphous capabilities to efficiently run single-threaded codes by exploiting instruction-level parallelism. While the TRIPS processor core belongs to the Grid Processor family of architectures, it differs in important aspects from previous work.

To achieve high ILP, the D-morph configuration treats the instruction buffers in the processor core as a distributed, large instruction issue window. This approach enables out-of-order execution using the TRIPS ISA without relying on associative issue window lookups typical in conventional machines. Effective utilization of the instruction buffers as a large window necessitates high-bandwidth instruction fetching, aggressive control and data speculation, and a memory system with high bandwidth and low latency, preserving sequential memory semantics across a window of thousands of instructions.

T-morph: Thread-Level Parallelism

The T-morph aims to boost processor utilization by assigning multiple threads of control to a single TRIPS core. While it shares execution resources (ALUs) and memory banks like simultaneous multithreading (SMT), the T-morph statically divides the reservation station (issue window) and eliminates some replicated SMT structures, such as the reorder buffer.

Two strategies for partitioning a TRIPS core to support multiple threads are row processors and frame processors. Row processors allocate one or more rows of the ALU array per thread, providing each thread with I-cache and D-cache bandwidth and capacity proportional to the number of rows assigned. However, threads mapped to bottom rows face non-uniform access to the register file. Frame processors time-share the processor by assigning threads to unique sets of physical frames.

S-morph: Data-Level Parallelism

The S-morph optimizes the array of ALUs and inter-ALU communication network for streaming media and scientific applications. These applications typically exhibit DLP with predictable loop-based control flow, large datasets, regular access patterns, and high computation intensity. Inspired by the Imagine architecture, the S-morph employs the Imagine execution model where a control thread sequences a set of stream kernels.

Results

D-morph Results

The authors evaluate the ILP achieved using D-morph mechanisms. The results are based on a 4x4 (16-wide issue) core with 128 physical frames, a 64KB L1 data cache requiring three cycles to access, and a 64KB L1 instruction cache partitioned into 4 banks. Other parameters include 0.5 cycles per hop in the ALU array, a 10-cycle branch misprediction penalty, a 250Kb exit predictor, a 12-cycle access penalty to a 2MB L2 cache, and a 132-cycle main memory access penalty.

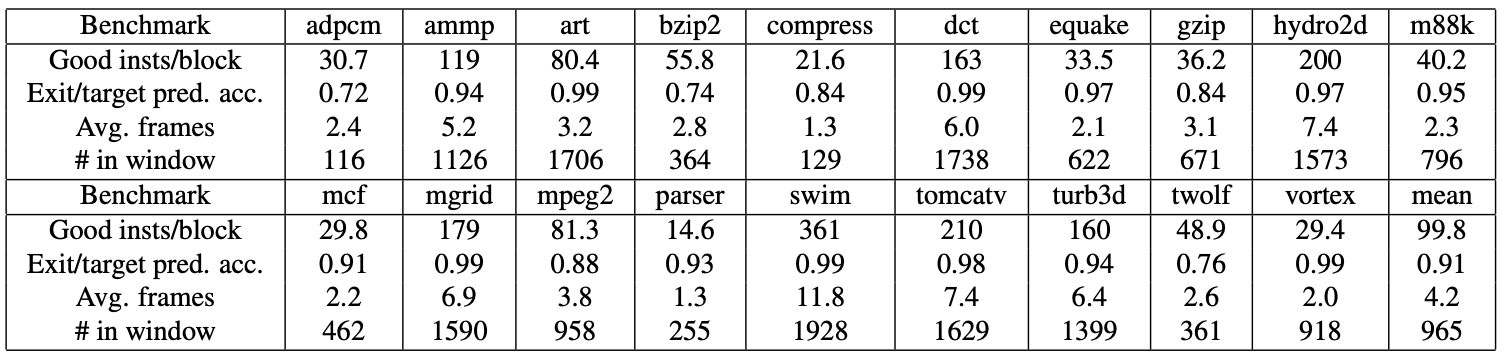

The compilers used for the binaries were Trimaran tool set, and they were scheduled for the TRIPS processor using a custom scheduler/rewriter. The first row of Figure 2 displays the average number of useful dynamically executed instructions per block, while the second row shows the average dynamic number of frames allocated per block for a 4x4 grid.

The third row indicates steady-state block (exit) prediction accuracies and the fourth row shows that each benchmark holds, on average, 965 useful instructions in the distributed window.

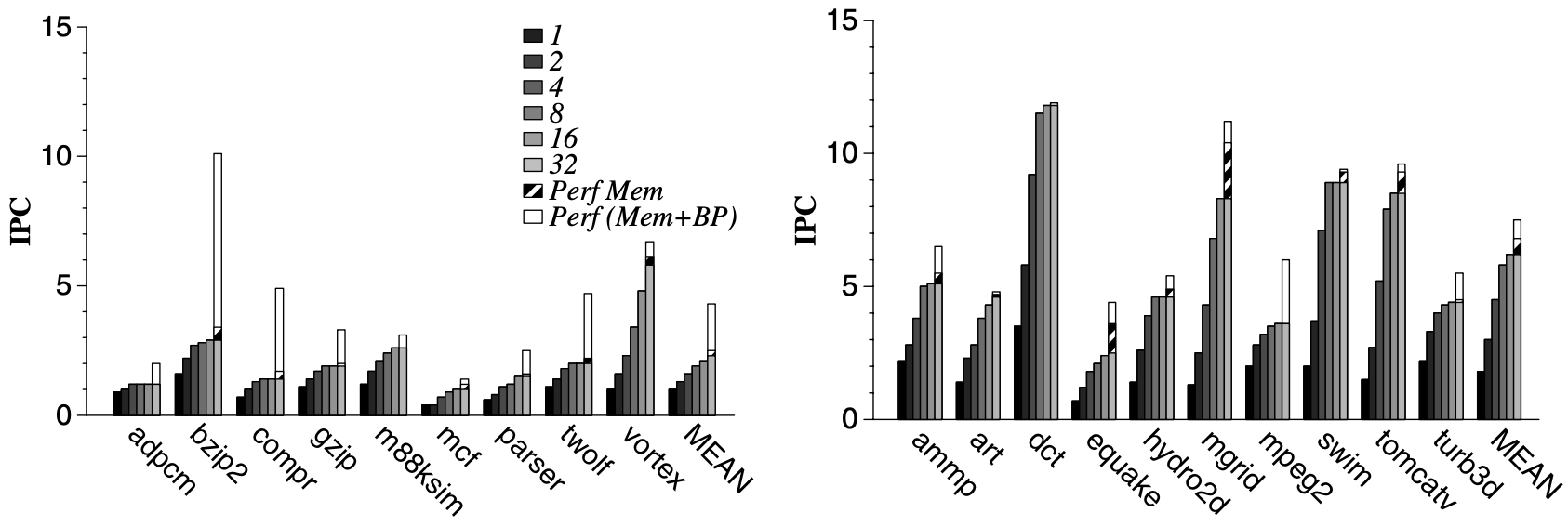

Figure 3 illustrates how Instructions Per Cycle (IPC) scales with increasing A-frames from 1 to 32, allowing for deeper speculative execution. Integer benchmarks are depicted on the left, while floating point and Mediabench benchmarks are on the right. Each 32 A-frame bar includes two additional IPC values, showing performance with perfect memory and perfect branch prediction.

Increasing the number of A-frames generally enhances performance across many benchmarks by facilitating greater ILP exploitation. However, some benchmarks show no performance improvements beyond 16 A-frames, while a few peak at 8 A-frames due to low hyperblock predictability or a lack of program ILP.

The graphs indicate that control mispredictions significantly impact performance for integer codes, but the large window effectively mitigates memory latencies, resulting in minimal slowdowns due to an imperfect memory system for all benchmarks except mgrid.

T-morph Results

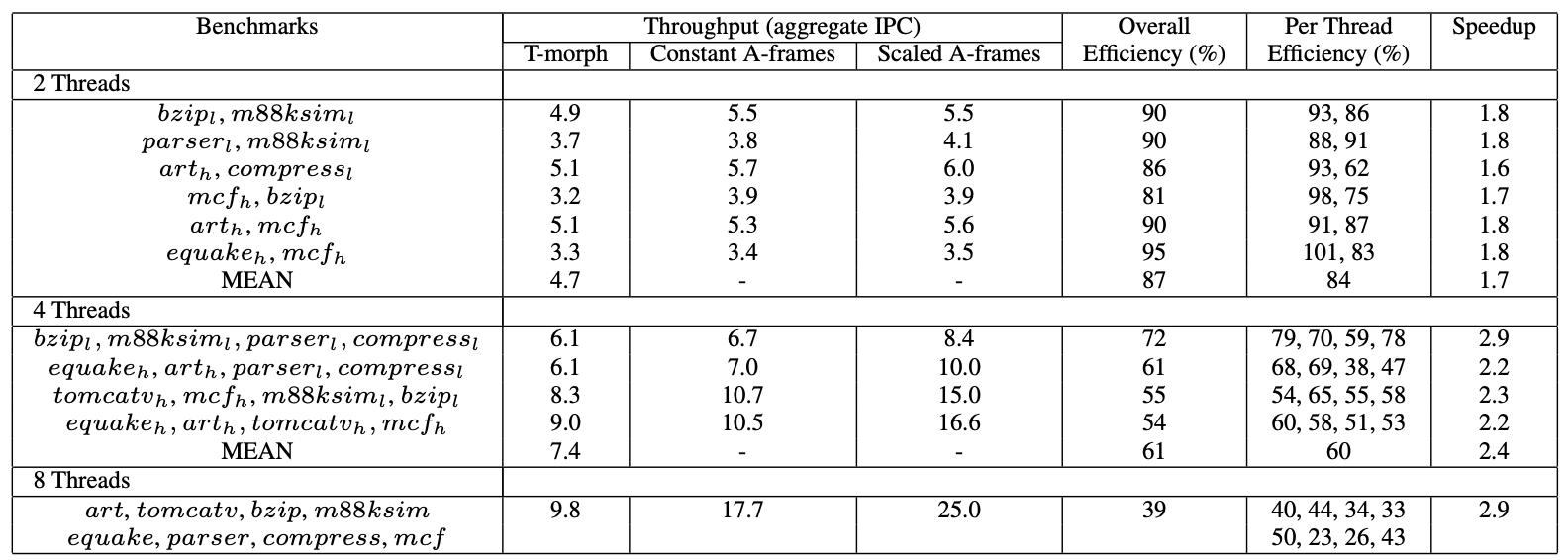

To assess multi-programmed workloads on the T-morph, applications were categorized as high memory intensive" orlow memory intensive” based on L2 cache miss rates. Eight benchmarks were chosen, including arth, mcfh, equakeh, tomcatvh (high memory intensive), and compressl, bzip2l, parserl, m88ksiml (low memory intensive). Various combinations of 2, 4, and 8 benchmarks were executed concurrently to examine performance and identify sources of degradation.

Running threads concurrently introduces performance loss due to: a) inter-thread contention for ALUs and routers, b) cache pollution, c) interference in branch predictor tables, and d) reduced speculation depth caused by fewer available frames per thread compared to the D-morph.

Figure 4 presents T-morph performance on a 4x4 TRIPS core, similar to the D-morph baseline. Column 2 displays combined instruction throughput of running threads, while column 3 shows IPC sum of benchmarks when each runs on a separate core with the same frame allocation as in T-morph. The difference between columns 3 and 2 indicates performance drop due to inter-thread interaction. Column 4 illustrates cumulative IPCs of threads when each runs alone on a TRIPS core with all frames available, revealing the combined impact of inter-thread interaction and reduced speculation in T-morph.

Experiments showed T-morph performance is mostly unaffected by cache and branch predictor pollution but is sensitive to instruction fetch bandwidth stalls.

Column 5 presents overall T-morph efficiency, defined as the ratio of multithreading performance to independent core throughput (column 2/column 4). Column 6 breaks down efficiency further, showing the fraction of peak D-morph performance achieved by each thread. The last column estimates speedup provided by T-morph compared to running each application sequentially on a single TRIPS core.

Overall efficiency ranges from 80–100% with 2 threads down to 39% with 8 threads. Low memory benchmarks provided highest efficiency, while mixes of high memory benchmarks had lowest efficiency due to increased cache contention. The overall speedup from multithreading ranges from 1.4 to 2.9 depending on the number of threads.

In summary, most benchmarks don’t fully utilize deep speculation offered by all A-frames in D-morph due to branch mispredictions. T-morph converts less useful A-frames to non-speculative computations when multiple threads are available.

S-morph Results

The performance of the TRIPS S-morph was evaluated on a selection of streaming kernels extracted from the Mediabench benchmark suite. These kernels, chosen to represent various computation-to-memory ratios, were manually coded in TRIPS meta-assembly language and scheduled onto the ALU array using a custom scheduler similar to that of the D-morph. Simulations were conducted using an event-driven simulator designed to model the TRIPS S-morph.

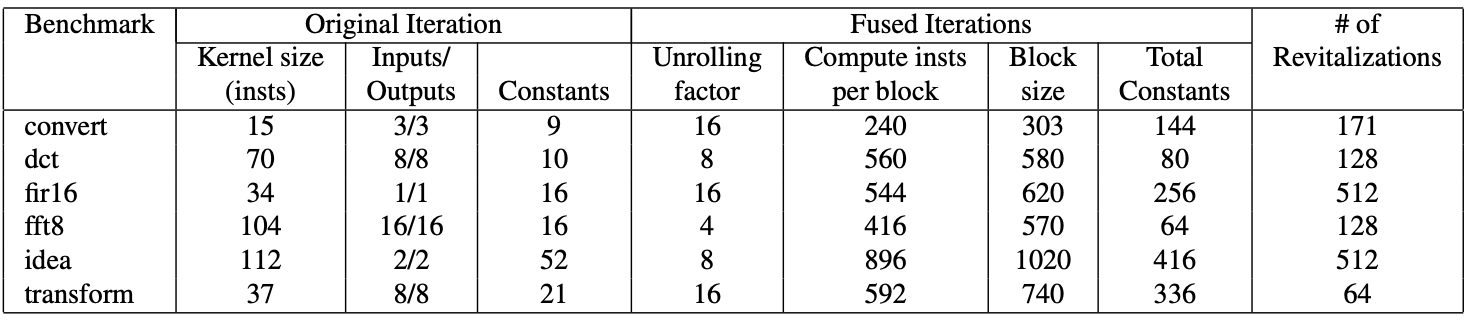

Program Characteristics: In Figure 5, the intrinsic characteristics of each kernel iteration are presented, including arithmetic operations, memory read/write bytes, and unique runtime constants. The unrolling factor for inner loops is determined based on the kernel size and the capacity of the super A-frame. Useful instructions per block represent computation instructions, while block size numbers encompass overhead instructions. The total constant count indicates the reservation stations filled with constant values for each iteration. Unrolling is based on 64-Kbyte input/output streams stored in the SRF.

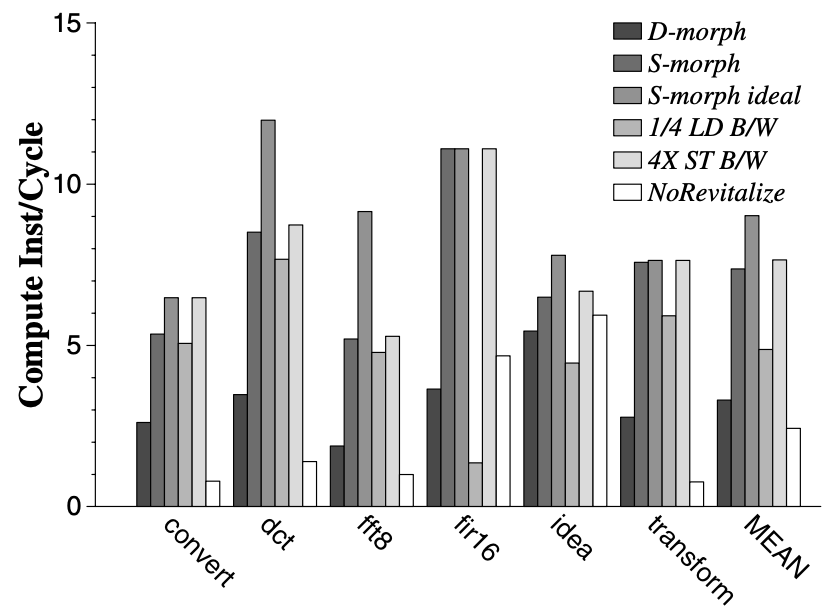

Performance Analysis: Figure 6 illustrates the comparison between D-morph and S-morph performance on a 4x4 TRIPS core under specific configurations. The S-morph sustains an average of 7.4 computation instructions per cycle, 2.4 times higher than the D-morph. An idealized S-morph with 256 frames and no revitalization latency achieves 9 compute ops/cycle, 26% higher than the realistic S-morph. In comparison to the Tarantula architecture, which maintains 10 to 20 FLOPS per cycle, the S-morph demonstrates competitive performance on data-parallel workloads. A grid of 32 ALUs averages 15 compute ops per cycle. Additionally, the polymorphous approach offers superior area efficiency compared to Tarantula’s heterogeneous cores.

SRF Bandwidth: Two alternative S-morph design points were explored: decreased load bandwidth to 64 bits per row and increased store bandwidth to 256 bits per row. Decreasing load bandwidth led to performance drops of up to 31%, while augmented store bandwidth improved average IPC by 5%.

Revitalization: Eliminating revitalization caused a significant performance drop in the S-morph, showing an average factor of 5 decrease. This drop stems from additional latency in mapping instructions and redistributing constants on each unrolled iteration due to hard synchronization boundaries. Overlapping revitalization and execution is being explored as a solution to mitigate this impact, with potential extensions allowing individual ALUs to act as separate processors, benefiting applications with frequent data-dependent control flow.

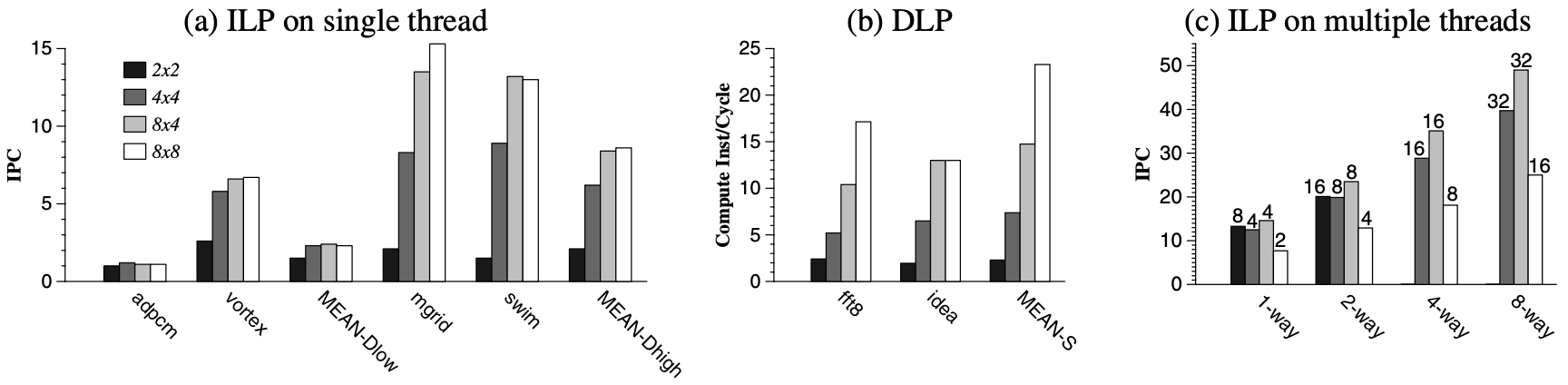

Scalability to Larger Cores

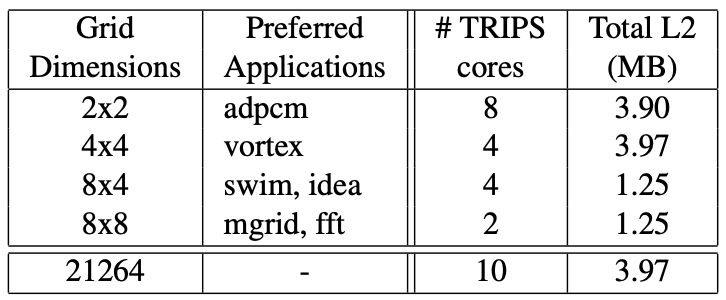

Figures 7(a) and 7(b) illustrate the combined performance of ILP and DLP workloads across TRIPS cores of different sizes: 2x2, 4x4, 8x4, and 8x8. The benchmarks selected represent the typical behavior of the entire suite. It was observed that benchmarks with low instruction-level concurrency derive little benefit from TRIPS cores larger than 4x4, while those with higher concurrency show diminishing returns beyond 8x4. Figure \ref{fig:TRIPS_CMP_designs} presents the most suitable configurations for each application in column 2.

The diverse requirements across applications necessitate both large coarse-grain processors (8x4 and 8x8) and small fine-grain processors (2x2). For single-threaded ILP and DLP applications, larger processors offer better aggregate performance, albeit with underutilization for some tasks. However, the decision becomes more intricate for multithreaded and multiprogrammed workloads.

Figure 8 outlines various TRIPS chip designs, from 8 2x2 TRIPS cores to 2 8x8 cores, assuming a $400mm^2$ die in a 100nm technology. Alternatively, the same area could accommodate 10 Alpha 21264 processors and 4MB of on-chip L2 cache.

Figure 7(c) depicts the instruction throughput (aggregate IPC), with each bar representing core dimensions and clusters showing the number of threads per core. The 2x2 array performs poorly with a large number of threads. The 4x4 and 8x4 configurations offer similar core numbers due to changes in on-chip cache capacity, while the 8x4 and 8x8 share the same total number of ALUs and instruction buffers across the chip. With numerous threads and up to 8 threads per core, the optimal design point is the 8x4 topology, regardless of the total thread count. This validates the large-core approach, indicating that one 8x4 core outperforms smaller cores for both ILP and DLP workloads, showing higher throughput than multiple smaller cores of the same area when many threads are available. Ongoing exploration involves space-based subdivision for both TLP and DLP applications, going beyond the time-based multithreading approach discussed in the paper.

Critical Review

Pros

- The paper introduces the concept of a polymorphous TRIPS system, which offers versatility in configuring processing and storage elements to suit various application domains. This flexibility allows for better optimization of performance and efficiency for different types of workloads.

- The paper provides a thorough evaluation of the performance of the TRIPS system across different application domains, demonstrating high performance in each mode (D-morph, T-morph, S-morph) for their respective workload types.

Cons

- While the paper proposes a novel concept and provides simulation-based performance evaluation, it does not present real-world implementation results.

- The paper discusses the benefits of polymorphous systems but does not extensively explore potential trade-offs or drawbacks associated with such systems.

Takeaways

The TRIPS system offers versatility, allowing for the configuration of processing and storage elements to suit various application domains. Unlike previous systems that utilize small components to construct larger processors, TRIPS begins with a large, scalable core that can be partitioned to support ILP, TLP, and DLP. The objective is to achieve performance and efficiency akin to specialized systems. This paper proposes a concise set of mechanisms for managing reservation stations and memory tiles in a large-core processor, facilitating adaptation into three modes for different application domains. It has been demonstrated that all three modes attain high performance in their respective domains: D-morph sustains 1–12 IPC on serial codes, T-morph achieves thread efficiencies of 87%, 60%, and 39% for two, four, and eight threads respectively, and S-morph executes up to 12 arithmetic instructions per clock on a 16-ALU core, and an average of 23 on an 8x8 core.

While the TRIPS system is presented with three distinct configurations (D, T, and S-morphs), each of these configurations comprises fundamental mechanisms that can be interchanged. Moreover, minor adjustments such as modifying the level-2 cache capacity do not necessitate alterations in the programming model. Designing interfaces between software and configurable hardware, and determining when and how to initiate reconfiguration, pose significant challenges for polymorphous systems. The exploration of hardware and software design issues is underway during the development of the TRIPS prototype system, considering options ranging from fixed static morphs to exposing configurable mechanisms for dynamic selection and reconfiguration by application layers.

References

- K. Sankaralingam, R. Nagarajan, H. Liu, C. Kim, J. Huh, D. Burger, S. Keckler, and C. Moore, “Exploiting ilp, tlp, and dlp with the polymorphous trips architecture,” in 30th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2003. Proceedings., 2003, pp. 422–433.