Research Paper Review: Systolic Architectures

As hardware costs decrease and processing requirements become clearer, specialized systems are increasingly developed; however, the lack of a standardized approach in their creation results in a dearth of methodological work and repeated errors. The paper proposes addressing this issue through the introduction of systolic architecture, offering a structured method for translating high-level computations into hardware configurations. In systolic systems, data flows rhythmically through multiple processing elements before returning to memory, providing advantages such as ease of implementation and reconfigurability to meet diverse needs due to their modular nature.

Paper Summary

Key Architectural Issues in Designing Special-Purpose Systems

Simple and Regular Design

Cost-effectiveness is a key consideration in designing special-purpose systems, where their cost must justify their limited use. Costs are typically divided into nonrecurring (design) and recurring (parts) costs. While part costs are decreasing due to advancements in integrated-circuit technology, design costs are more significant for special-purpose systems since they are not produced in large quantities. Therefore, for a special-purpose system to be preferable over a general-purpose one, its design cost must be relatively low. Additionally, significant savings can be achieved if a structure can be broken down into a few simple substructures used repetitively with straightforward interfaces. Special-purpose systems based on simple, regular designs are likely to be modular and adaptable to various performance goals, making them cost-effective.

Concurrency and Communication

There are essentially two methods to create a fast computer system: using fast components or utilizing concurrency. As technological advancements show a slowing growth rate in component speed, significant improvements in computation speed rely on employing many processing elements concurrently. However, with VLSI technology, coordination and communication become crucial due to routing costs dominating power, time, and area requirements for implementation. Therefore, the challenge lies in designing algorithms that facilitate high levels of concurrency while employing simple, regular communication and control mechanisms to enable efficient implementation.

Balancing Computation with I/O

In designing a special-purpose system, the consideration of I/O significantly impacts overall performance since such systems typically interact with a host for data input and output. The primary performance goal is to achieve a computation rate that balances the available I/O bandwidth with the host. Since accurately estimating available I/O bandwidth in complex systems is often difficult, it’s essential for the design of special-purpose systems to be modular, allowing for easy adjustment to various I/O bandwidths. The I/O challenge is not only about bandwidth but also about the available internal memory within the system. Consequently, it’s crucial to arrange computations with an appropriate memory structure to balance computation and I/O time. Particularly in scenarios where a large computation is executed on a small special-purpose system, the computation must be broken down to manage I/O efficiently, as processing subcomputations one at a time may incur significant I/O overhead. For problems like the n-point FT problem, the speed-up ratio achievable by a special-purpose device is limited by I/O considerations, independent of device speed. Understanding these I/O-imposed performance limits helps prevent excessive design complexity. In practice, problems often exceed the capacity of special-purpose devices, raising challenges for architects regarding computation decomposition to minimize I/O, the relationship between I/O requirements and system size/memory, and the impact of I/O bandwidth on achievable speed-up ratios.

Systolic architectures

A systolic system is made up of interconnected cells, each capable of simple operations. These cells are often organized into either a systolic array or a systolic tree to benefit from straightforward communication and control structures, which are easier to design and implement. Information moves between cells in a systolic system in a pipelined manner, and communication with external sources only happens at boundary cells.

Computational tasks fall into two main categories: compute-bound and I/O-bound computations. A compute-bound computation involves more operations than the total number of input and output elements, while an I/O-bound computation involves fewer operations. Improving the speed of an I/O-bound computation typically requires increasing memory bandwidth, which can be achieved through faster components or interleaved memories, albeit potentially at the cost of complexity. On the other hand, speeding up a compute-bound computation can often be done simply and inexpensively through the systolic approach.

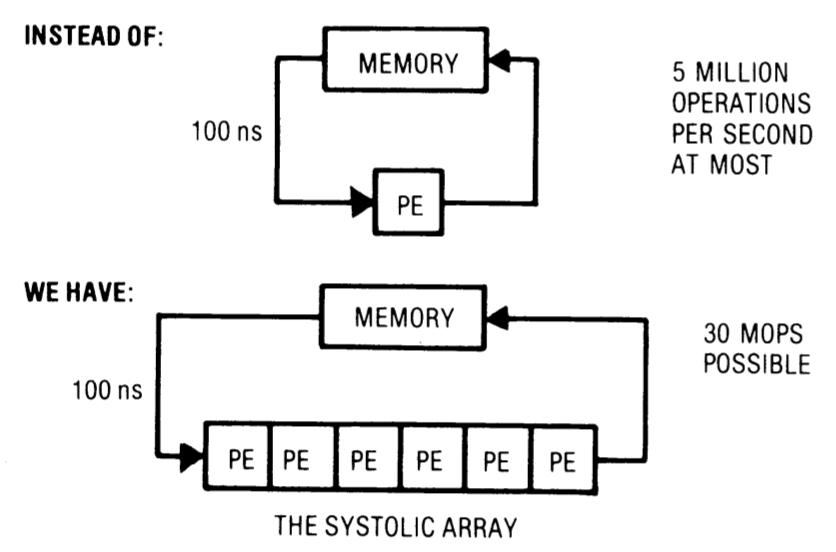

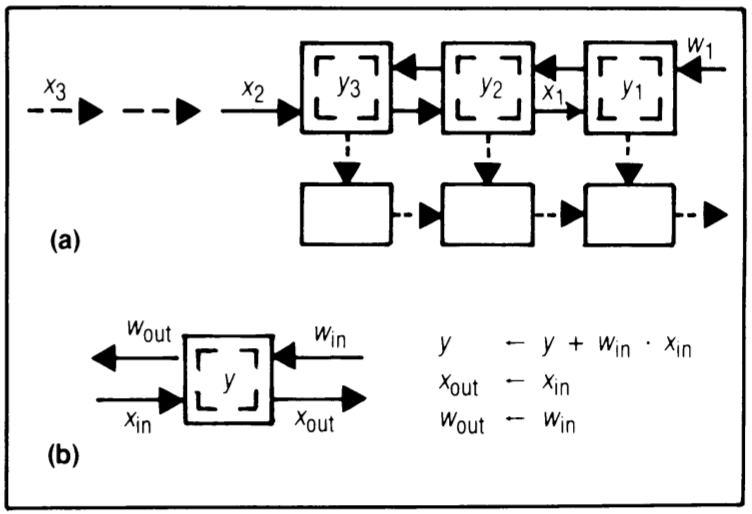

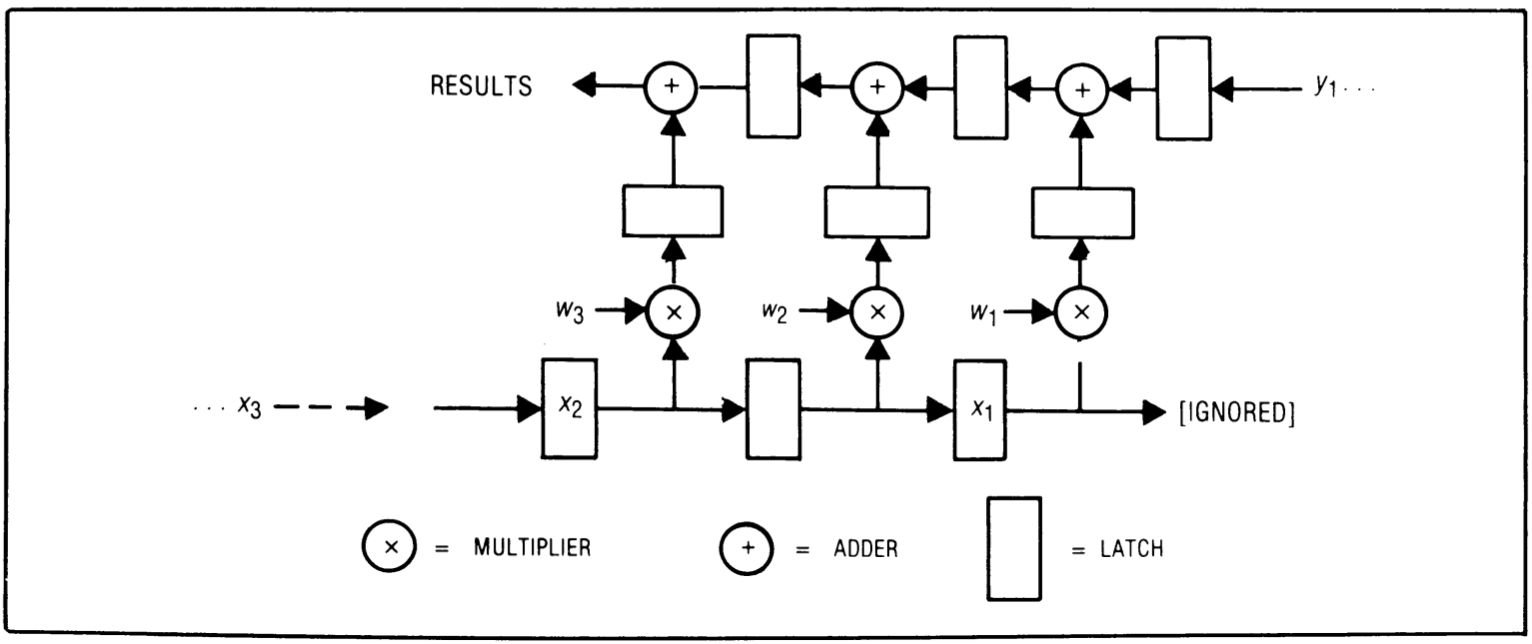

The core idea behind a systolic architecture, such as a systolic array, is depicted in Figure 1. By replacing a single processing element with an array of processing elements (PEs), or cells as referred to in this article, a higher computation throughput can be achieved without the need to increase memory bandwidth.

Systolic designs for the convolution computation

In this section, various systolic structures are exemplified through the presentation of a family of designs aimed at addressing the convolution problem. The convolution problem is defined as the process of deriving a resulting sequence (\(y_1, y_2, \ldots, y_{n+1-k}\)) from a sequence of weights (\(w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_k\)) and an input sequence (\(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n\)). This resulting sequence is computed using the formula: \(y_i = w_1 \cdot x_i + w_2 \cdot x_{i+1} + \ldots + w_k \cdot x_{i+k-1}\)

The convolution problem is compute-bound because each input \( x_i \) must be multiplied by each of the \( k \) weights. When \( k \) is large, fetching \( x_i \) separately for each multiplication from memory creates a bottleneck in memory bandwidth, hindering high-performance solutions. A systolic architecture addresses this I/O bottleneck by reusing each \( x_i \) fetched from memory multiple times.

(Semi-) Systolic Convolution Arrays with Global Data Communication

When an \( x_i \) is fetched from memory and broadcasted to multiple cells, it allows each cell to utilize the same \( x_i \). This broadcasting method is a clear way to maximize the usage of each input element. Conversely, fan-in gathers data items from various cells. Employing the fan-in technique is another direct approach to address the I/O bottleneck issue.

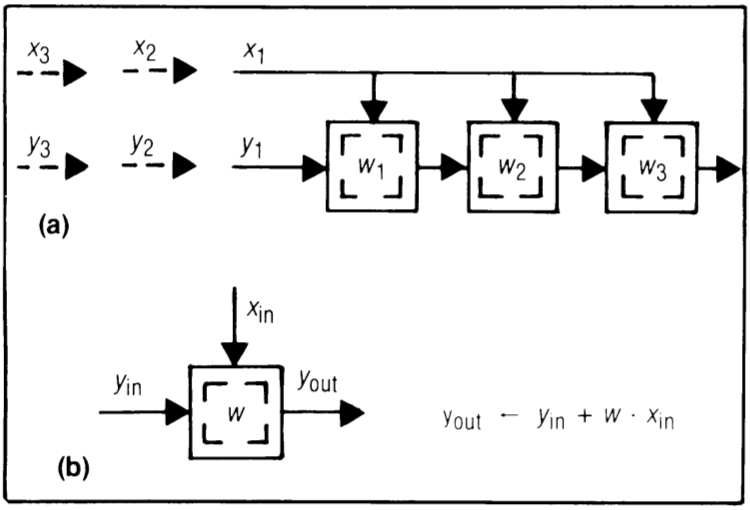

Design B1 - broadcast inputs, move results, weights stay

This design’s fundamental principle was previously suggested for circuits to implement both a pattern matching processor and polynomial multiplication circuits. (Figure 2)

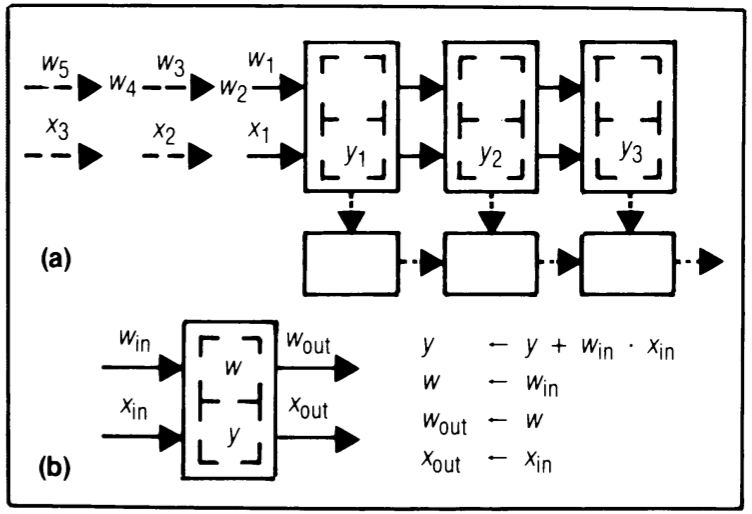

Design B2 - broadcast inputs, move weights, results stay

In design B2 (Figure 3), each \( y_i \) remains in a cell to accumulate its terms, optimizing the utilization of available multiplier-accumulator hardware. In contrast, in design B1 (Figure 2), the systolic path for \( y \)’s movement may be wider than that for \( w \)’s movement in design B2. This is because \( y_i \)’s usually carry more bits than \( w_i \)’s for numerical accuracy. Additionally, employing multiplier-accumulators in design B2 can enhance result precision, as extra bits can be retained in these accumulators at a reasonable cost. However, design B1 offers the advantage of not needing a separate bus to gather outputs from individual cells.

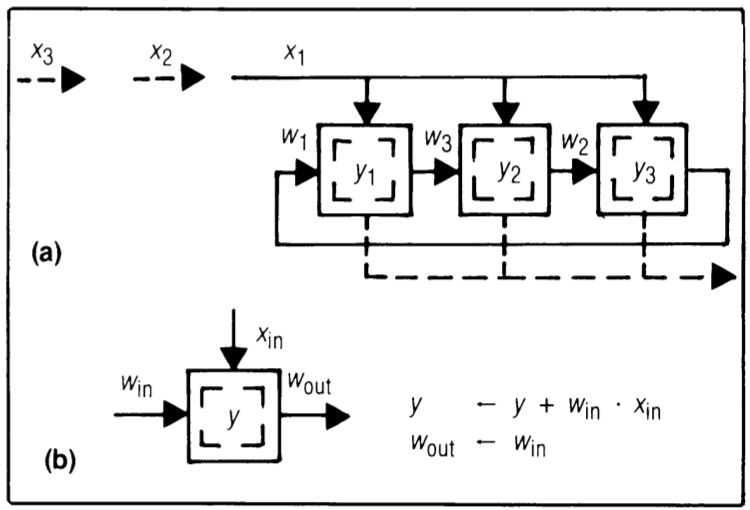

Design F - fan-in results, move inputs, weights stay

Designs employing unbounded fan-in have been recognized for quite some time, notably in signal processing and pattern-matching contexts. (Figure 4)

(Pure-) systolic convolution arrays without global data communication

While global broadcasting or fan-in effectively resolves the I/O bottleneck issue, implementing it in a modular and scalable manner poses another challenge. Distributing (or collecting) a data item to (or from) all cells of a systolic array in each cycle necessitates the use of a bus or a tree-like network. As the number of cells grows, the length of wires becomes problematic for both bus and tree structures. Expanding these non-local communication paths to accommodate increased demand without slowing down the system clock presents engineering challenges at chip, board, and higher system levels.

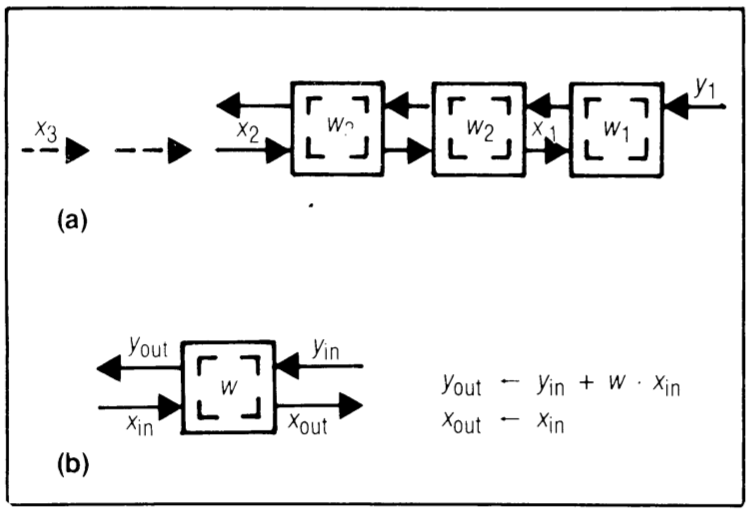

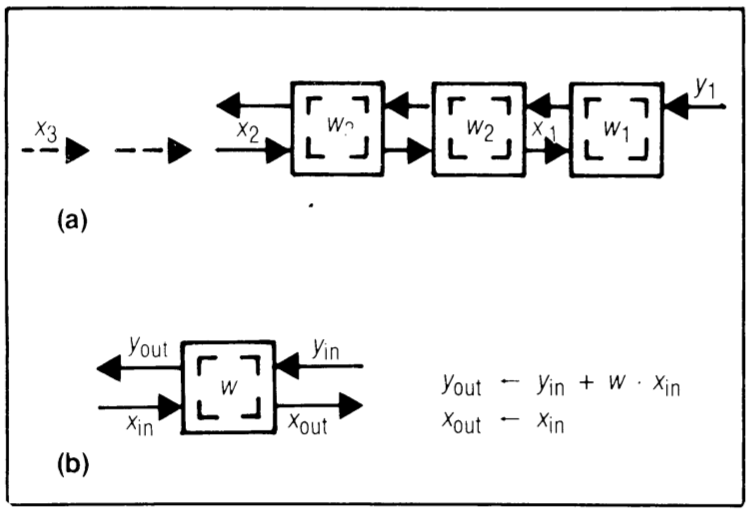

Design R1 - results stay, inputs and weights move in opposite directions

In design R1 (Figure 5), each partial result \( y_i \) is stored at a cell to accumulate its terms. \( x_i \)’s and \( w_i \)’s move in opposite directions systolically: when an \( x \) meets a \( w \) at a cell, they’re multiplied, and the product is added to the \( y \) at that cell. To ensure every \( x_i \) pairs with every \( w_i \), consecutive \( x_i \)’s and \( w_i \)’s are separated by two cycle times.

Similar to design B2, R1 efficiently uses available multiplier-accumulator hardware and uses a tag bit linked to the first weight \( w_i \) to trigger output and reset the accumulator contents of a cell. R1 eliminates the need for a global network for output collection; a systolic output path suffices. Because consecutive \( w_i \)’s are well separated, conflicts, like multiple \( y_i \) reaching a single latch simultaneously, are avoided. Moreover, \( y_i \)’s naturally output from the systolic output path in order \( y_1, y_2, \ldots \).

This design’s fundamental concept, including the systolic output path, is applied in a pattern-matching chip implementation. To maximize throughput, two independent convolution computations can be interleaved in the same systolic array. However, slight modifications to array cells would be necessary to support this interleaved computation, like adding an extra accumulator to hold a temporary result for the other convolution computation.

Design R2 - results stay, inputs and weights move in the same direction but at different speeds

In this setup (Figure 6), both the \( x \) and \( w \) data streams move from left to right systolically, but the \( x \)’s move twice as fast as the \( w \)’s. Compared to design R1, this approach ensures that all cells are active throughout a single convolution, but it necessitates an additional register in each cell to store a \( w \) value. This algorithm has been employed in implementing a pipeline multiplier.

There exists a dual version of design R2 where the \( w_i \)’s move twice as fast as the \( x_i \)’s. In this dual design, each cell requires a register to store an \( x \) value instead of a \( w \) value to introduce delays for the \( x \) data stream. This dual design becomes preferable in scenarios where the \( w_i \)’s carry more bits than the \( x_i \)’s.

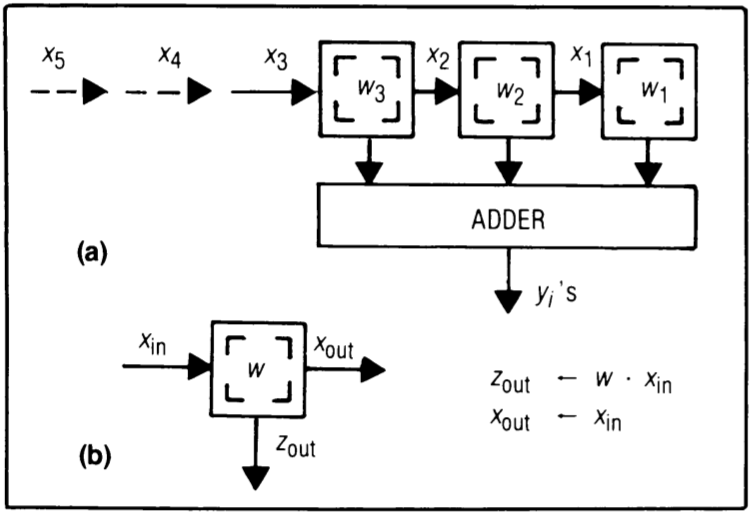

Design W1 - weights stay, inputs and results move in opposite directions

These designs (Figure 7) don’t maximize the use of available multiplier-accumulator hardware efficiently. However, under certain conditions, they may offer better efficiency than other designs. Since the same set of weights is used for computing all \( y_i \)’s and different sets of \( x_i \)’s are used for each \( y_i \), it’s natural to preload the \( w_i \)’s into the cells and keep them there, while allowing the \( x_i \)’s and \( y_i \)’s to move along the array.

This design serves as a foundation because it can naturally expand to perform recursive filtering and polynomial division. Similar to design R1, consecutive \( x_i \)’s and \( y_i \)’s are separated by two cycle times. Notably, since the systolic path for moving the \( y_i \)’s already exists, there’s no need for another systolic output path as seen in designs R1 and R2.

Thus, this systolic array can output a \( y_i \) every two cycle times with a consistent response time. However, Design W1 suffers from the same drawback as Design R1: only about half the cells work at any given time unless two independent convolution computations are interleaved in the same array. The following design, akin to Design R2, addresses this limitation by having both the \( x_i \)’s and \( y_i \)’s move in the same direction but at different speeds.

Design W2 - weights stay, inputs and results move in the same direction but at different speeds

In design W2 (Figure 8), all cells are active continuously, unlike in design W1 where only about half of the cells work at any given time. However, it sacrifices one advantage of design W1: the constant response time. In design W2, the output of \( y_i \) occurs \( k \) cycles after the last of its inputs begins entering the left-most cell of the systolic array.

This design has been expanded to handle 2-D convolutions, prioritizing high throughputs over rapid responses. Similar to design R1, design W2 also has a dual version where the \( x_i \)’s move twice as fast as the \( y_i \)’s.

The designs mentioned above are just a few examples of systolic designs for the convolution problem. Other possibilities exist, such as designs where results, weights, and inputs all move during each cycle. It could also be beneficial to integrate a “cell memory” within each cell capable of storing a set of weights. With this feature, weights can be selected dynamically using a systolic control path, enabling interpolation or adaptive filtering.

Moreover, the flexibility provided by cell memories and systolic control allows the same systolic array to perform various functions. For instance, the ESL systolic processor utilizes cell memories to execute multiple functions, including convolution and matrix multiplication.

Selecting the right design for a given environment requires a thorough understanding of each design’s strengths and weaknesses.

While a single multiplier-accumulator hardware component is often a cost-effective solution for each cell in a systolic convolution array, separating the multiplier and adder can sometimes improve throughput by allowing their executions to overlap. Figure 9 illustrates such a modification to design W1, which can also be applied to other systolic convolution arrays.

Another consideration is the implementation of individual cells directly on a single chip, where the chip pin bandwidth becomes a bottleneck. In such cases, semi-systolic arrays, like designs B1 and F, may be preferred for their lower pin requirements, despite requiring global communication.

Results

After discussing a range of systolic convolution arrays, the analysis can now offer clearer recommendations and assessments regarding criteria for designing systolic structures.

-

The design makes multiple use of each input data item: Systolic systems can attain high throughputs with minimal outside communication bandwidth due to their inherent property. To fulfill this requirement, one can employ global data communications like broadcast and unbounded fan-in, or each input can traverse an array of cells for use at each cell. The latter approach is preferred for the modular expandability of the resulting system.

-

The design uses extensive concurrency: The processing efficiency of systolic architecture lies in its simultaneous utilization of numerous simple cells, contrasting with the sequential use of powerful processors in conventional architectures. When memory speed surpasses cell speed, employing two-dimensional systolic arrays ensures optimal utilization of memory bandwidth by allowing all I/O ports on array boundaries to input or output data items during each cell cycle. The choice between one- or two-dimensional schemes depends heavily on how cells and memories will be implemented. In practice, systolic arrays can be interconnected to build resilient systems capable of dynamically generating the least-squares fit to all received data up to any given moment.

-

There are only a few types of simple cells: To meet performance objectives, a systolic system often employs a large number of simple cells, limited to only a few types to minimize design and implementation expenses. However, there’s always a trade-off between cell simplicity and flexibility.

-

Data and control flows are simple and regular: Pure systolic systems exclusively rely on the system clock for global communication, avoiding long-distance or irregular wires for data transmission. However, in large two-dimensional arrays, the global clock may need to be slowed down to address clock skews. Despite this potential issue, systolic designs remain entirely modular and expandable, devoid of challenging synchronization or resource conflict problems. Moreover, systolic systems eliminate software overhead associated with operations like address indexing, leading to significant performance enhancements compared to conventional general-purpose computers. Additionally, their simple, regular control and communication facilitate straightforward and area-efficient layout or wiring, which is particularly advantageous in VLSI implementation.

In summary, systolic designs meeting these criteria are simple, modular, expandable, and deliver high performance, making them suitable for special-purpose systems. A distinctive feature of the systolic approach is that as the number of cells increases, both system cost and performance rise proportionally, provided the problem size is sufficiently large. For instance, a systolic convolution array can effectively utilize a large number of cells if the kernel size (number of weights) is substantial. This sets systolic systems apart from other parallel architectures, which are typically cost-effective only for a small number of processors. Moreover, from a user perspective, systolic systems are easy to use.

Critical Review

Pros

- Systolic architectures can achieve high processing speeds by utilizing parallel processing across multiple simple processing elements simultaneously.

- They are efficient in terms of hardware utilization, as they make use of simple processing elements that can be replicated and interconnected to perform complex computations.

- Systolic architectures are often scalable, allowing for easy expansion by adding more processing elements, making them suitable for handling large-scale computations.

- They often feature a regular and structured design, which simplifies hardware implementation and facilitates efficient communication between processing elements.

Cons

- Systolic architectures are typically designed for specific applications and may lack the flexibility to adapt to different computational tasks without significant redesign.

- Implementing systolic architectures with a large number of processing elements can be costly in terms of hardware resources, especially for custom hardware implementations.

- The paper would have been more persuasive if it had included a comparison of speedup achieved by systolic architectures in contrast to general-purpose processors.

Takeaways

Bottlenecks in speeding up computations often stem from limited system memory bandwidths, known as von Neumann bottlenecks, rather than restricted processing capabilities themselves. Systolic architectures, facilitating multiple computations per memory access, can accelerate compute-bound computations without increasing I/O demands. Generally, systolic designs are applicable to any regular compute-bound problem involving repetitive computations on extensive data sets. While various systolic designs exist, the automation of their design remains an open question, along with challenges in specifying and verifying systolic structures. However, the overarching objective is the effective utilization of systolic processors in general computing environments to offload regular, compute-bound computations, requiring further research in two main areas. Firstly, in system integration, there’s a need for a convenient method to incorporate high-performance systolic processors into complete systems and comprehend their efficient utilization. Secondly, in specifying building blocks for various systolic processors, enabling these blocks to be programmed to form basic cells for numerous systolic systems once constructed.

References

- Kung, “Why systolic architectures?” Computer, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 37–46, 1982.