Research Paper Review: The Raw Microprocessor

This paper introduces the Raw microprocessor, which employs a scalable ISA to solve the growing wire-delay problem. By offering a parallel, software interface to gate, wire, and pin resources on the chip, Raw presents an architecture with direct analogs to these physical resources. Such an approach empowers programmers to attain maximum performance and energy efficiency amidst wire delay constraints.

Paper Summary

As the processor clock frequencies have rapidly risen, the portion of the chip that is accessible by a signal in a single clock cycle has decreased exponentially. This decline necessitates architects to consider wire delays in their designs. Despite efforts in materials and process changes, the issue persists. To mitigate this, designers strategically position logic elements to minimize the distance between communicating transistors. Unlike before, where silicon area determined logic reuse, designers now duplicate logic as needed to shorten wire lengths.

In future designs, the gap between software-accessible processing resources and the actual physical resources will widen. The management logic area far exceeds that of ALUs, leading to more non-deterministic system performance reliant on program implementation specifics. Additionally, power consumption and the costs of designing and verifying complex architectures are increasing. In response to these challenges, the paper proposes the Raw microprocessor, which aims to minimize the ISA gap by exposing underlying physical resources as architectural entities. Raw employs a scalable ISA that offers a parallel software interface to the gate, wire, and pin resources of a chip.

The Raw Microprocessor

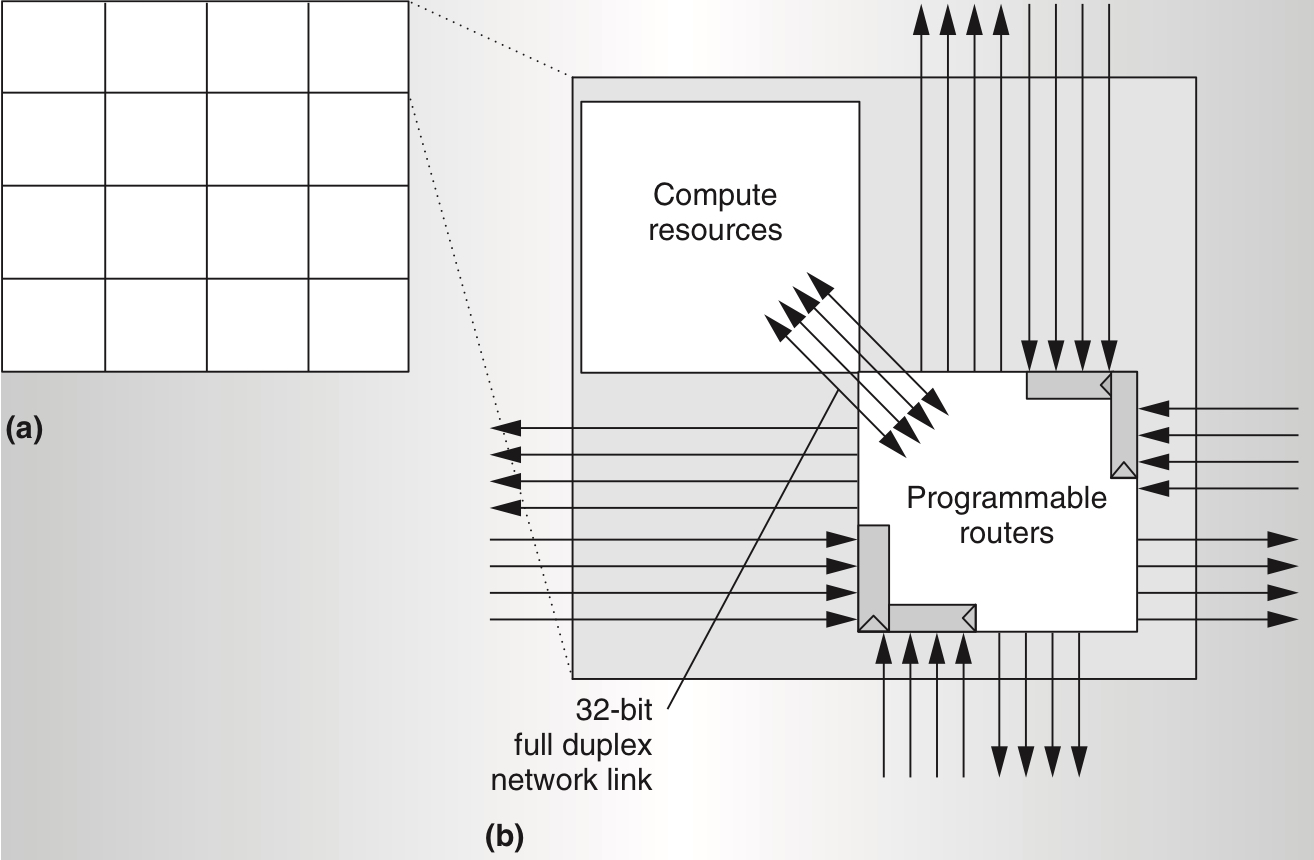

The Raw processor design features 16 identical programmable tiles, each equipped with static and dynamic communication routers, MIPS-style processor, floating-point unit, and data and instruction caches. Each tile’s size is optimized to allow a signal to traverse in a single clock cycle. Interconnections between tiles utilize four 32-bit full duplex on-chip networks, two static (routes specified at compile time), and two dynamic (routes specified at run time), with each tile only connecting to its neighbors (Figure 1). Wires are registered at the input of their destination tile, i.e. the length of the longest wire is no longer than the length/width of a tile, thus ensuring high clock speeds and architecture scalability. The Raw ISA exposes these on-chip networks to the software, enabling direct programming of wiring resources for efficient data transfer between tile components, essentially abstracting wire delay as network hops.

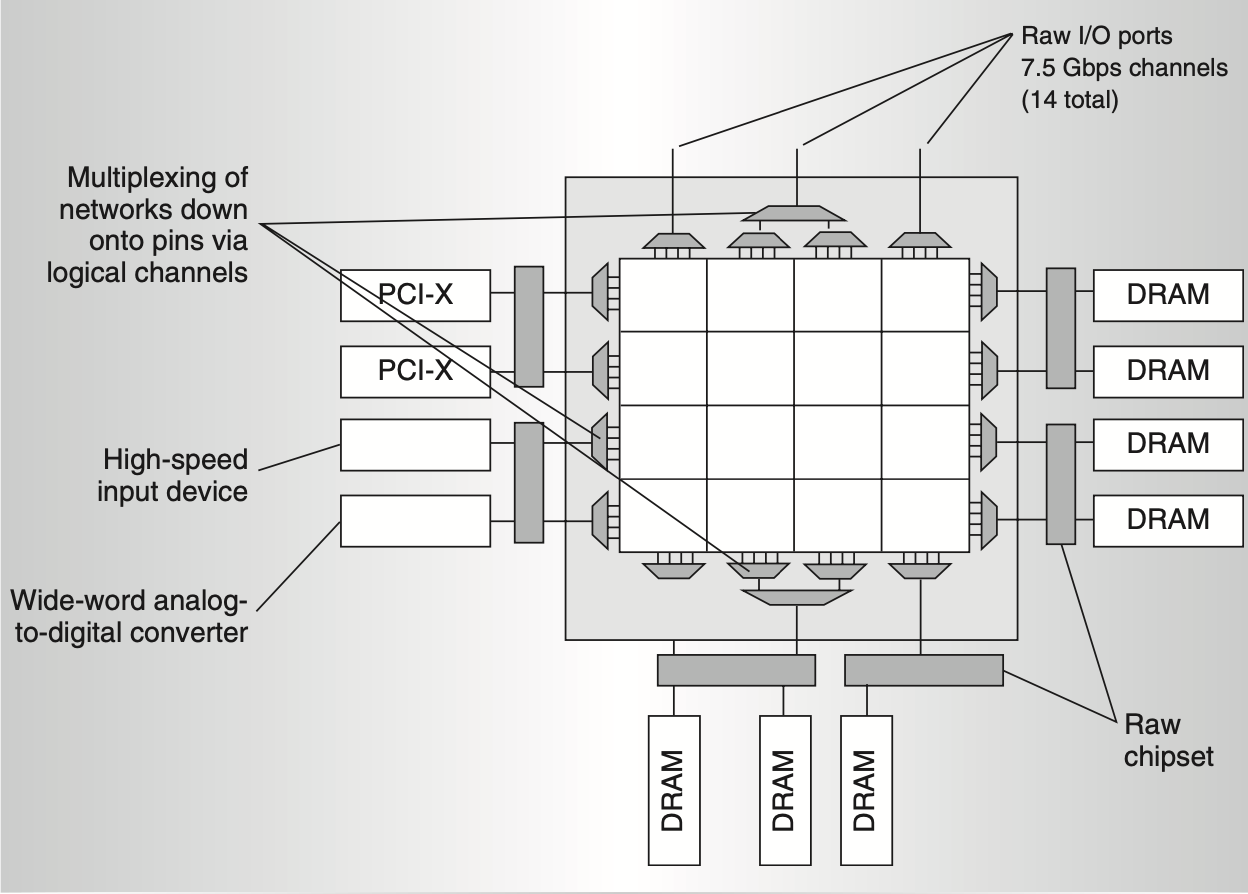

At the network edges, buses are hardware multiplexed onto chip pins using logical channels (Figure 2). To activate a pin, users program the on-chip network to route data off the array’s side. The Raw I/O port offers a high-speed, simple, and flexible word-oriented abstraction, allowing system designers to adjust I/O device quantities based on application requirements. Besides transferring data directly to tiles, off-chip devices connected to Raw I/O ports can utilize on-chip networks to access other devices for direct memory transfers.

Architectural Entities

The growing importance of gate resources, wire delay, and pins necessitates dedicated architectural entities, similar to the multiply instruction for physical multipliers. Raw ISA responds by directly exposing these entities, ensuring backward compatibility for future generations. With its more direct interfaces, Raw processors accommodate more functional units and boast flexible, efficient pin utilization. Consequently, high-end Raw processors feature increased pin counts, enhancing performance and functionality. They also offer greater predictability and higher clock frequencies, improving scalability. As the design lacks centralized resources, global buses, or structures that expand with processor scaling; wire length, design complexity, and verification complexity remain consistent, independent of transistor count.

Application Domains

The Raw microprocessor executes computations that encompass those performed on general-purpose processors, offering a broader range of capabilities. Applications capable of utilizing customized placement and routing, abundant gates, and programmable pin resources in an ASIC process can also benefit from analogous architectural resources in the Raw microprocessor. Unlike ASICs, Raw applications can be developed in high-level languages like C, Java, or emerging languages like StreamIt, with compilation completed in minutes rather than months. Applications leveraging the Raw static network’s ASIC-like place-and-route capability are termed software circuits, capable of running as dedicated embedded hosts or processes on general-purpose machines.

Application Mapping

The Raw operating system supports both space and time multiplexing of processes. This means that a Raw processor can handle multiple independent processes simultaneously and switch between them like a conventional processor. The operating system assigns a proportional number of tiles to each process based on its computational requirements. It employs gang scheduling to facilitate communication between physical threads of a process. Continuous or real-time applications can be prioritized to prevent interruption, and some tiles can be put into sleep mode to conserve power.

To optimize performance, operations are distributed across tiles to minimize congestion, and the compiler configures network routes between these operations, akin to designing a customized hardware circuit. This customization can be done using Raw’s assembly code as well. The Raw network can transfer data from the output of one ALU tile to the input of a neighboring ALU tile within three cycles.

Design Decisions

To ensure efficient execution of software circuits and scalable architectural constructs, Raw Tile utilizes its compute processor, static router, and dynamic router. The static router manages static networks, facilitating low-latency communication crucial for software circuits and other applications with predictable communication needs at compile-time. Meanwhile, dynamic routers handle dynamic networks, which transport unpredictable operations such as interrupts, cache misses, and compile-time unpredictable communication between tiles.

The compute processor integrates network interfaces directly into its pipelines. These networks are register-mapped and embedded into the processor’s bypass paths. To manage data flow, the processor stalls during the register fetch stage if necessary data isn’t available in the input FIFO buffer or if the output buffer lacks sufficient space to store the result. Additionally, the instruction format includes a bit allowing specification of two output destinations: either a network or register. This flexibility enables tiles to retain local copies of transmitted values. Consequently, the Raw static network achieves custom scalar data routing with minimal latency comparable to ASICs. Moreover, to address changes in semantics, the commit point of the compute processor is relocated to the execute stage.

For software circuits and parallel scalar codes, we utilize two static networks to efficiently transfer values between tiles. These networks provide ordered, flow-controlled, and dependable transfer of single-word operands and data streams among the functional units of the tiles. The static router operates as a five-stage pipeline overseeing two routing crossbars, each facilitating value routing among seven entities including the static router pipeline, neighboring tiles, compute processor, and the other crossbar. Each word transferred on the static network requires a corresponding instruction in the instruction memory of every router along its path, typically programmed at compile time and cached like compute processor instructions. Consequently, the static routers collectively reconfigure the network’s entire communication pattern cycle by cycle. By anticipating routes well in advance, route preparations can be pipelined, enabling immediate data word routing upon arrival, crucial for exploiting ILP in scalar codes. Unlike static routers, dynamic routers have more latency and are better suited for long data streams rather than scalar transport. Flow control in the static router ensures that instructions progress only after completing all routes, guaranteeing incoming words reach destination tiles in a predetermined order, even amidst unpredictable events.

To transmit a message via the dynamic network, the user inputs a single header word containing the destination tile (or I/O port), a user field, and the message length. Each hop on this network takes one cycle, with an additional cycle required for every turning hop. One major concern with dynamic networks is deadlock resulting from excessive use of buffering resources.

To address this, the Raw processor’s memory network adopts a restricted usage model employing deadlock avoidance, while the general network operates with unrestricted usage and utilizes deadlock recovery. In the event of deadlock in the general network, an interrupt routine is triggered, leveraging the memory network for recovery. Trusted clients such as the operating system, data cache, interrupts, hardware devices, DMA, and I/O utilize the memory network, ensuring they do not block on a network send unless they can handle incoming messages. Alternatively, a client can avoid blocking on a network send if it possesses sufficient private buffering resources along the message path.

Untrusted clients utilize the general network and rely on hardware deadlock recovery mechanisms to maintain progress during deadlock situations. The general network is a user-level construct and is virtualized for each group of tiles that are part of a process. The contents of the general and static networks are saved off on a context switch and the process and its network data can be restored at any time to a new offset on the grid. Both hardware caches and software utilize the memory network. Additionally, the Raw processor supports parallel implementation of external interrupts, enabling each tile to process interrupts independently.

Results

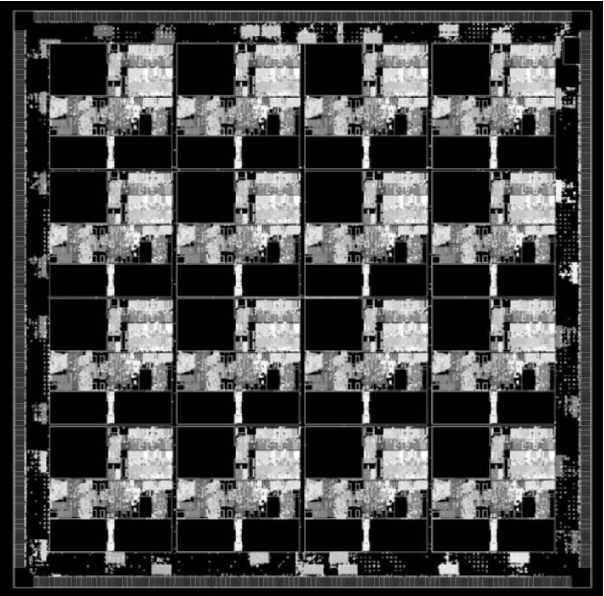

The Raw chip 16-tile prototype was implemented using IBM’s SA-27E, 0.15-micron, six-level copper, ASIC process. The chip measures 16\(\times\)16mm on an 18.2\(\times\)18.2mm die to accommodate a high-pin count package, providing 1657 pins, including 1080 high-speed transceiver logic I/O pins. Estimated power consumption is 25W, with a worst-case frequency of 225 MHz (typically 25% higher in the average case). Despite aggressive pipelining of the processor and conservative treatment of control paths, wire delay within the tile proved significant, necessitating careful placement considerations. To address this, the researchers developed a library of routines for automated placement of structured logic within the tile and around the chip perimeter. Figure 3 illustrates structured logic placement within the tile, while Figure 4 depicts chip-wide placement. Synthesis, back-end processing, and placement infrastructure collectively transform Verilog source code into a successfully placed chip in approximately 6 hours on a single machine.

Applications with limited ILP typically don’t see significant benefits from running on Raw. However, for scalar codes with moderate ILP, RawCC (C and Fortran compiler) effectively exploits parallelism by automatically partitioning the program graph, placing operations, and programming routes for the static router. This results in speedups ranging from 6\(\times\) to 11\(\times\) for 16-tile Raw processors and 9\(\times\) and 19\(\times\) for 32 tiles compared to a single-tile performance on \textit{Specfp} applications. Yet, when application parallelism is restricted, RawCC achieves similar speedups to hand-parallelized code but may require up to twice as many tiles.

Structured applications with pipelined parallelism or heavy data movement benefit from careful orchestration and layout of operations and network routes, ensuring maximal performance. For these applications and operating system code, a specialized version of the GNU C compiler allows programmers to specify code and communication on a per-tile basis.

Critical Review

Pros

- The paper presents a novel approach to processor design, focusing on minimizing wire delay and maximizing performance through architectural innovations.

- The Raw microprocessor design demonstrates scalability in handling multiple processes and parallelism efficiently.

- Raw offers customization options for both hardware and software, allowing for tailored solutions to specific application needs.

- The use of specialized compilers and parallel processing techniques leads to significant performance improvements for certain types of applications.

- The use of a replicated tile design streamlines various phases of the project, reducing the time and effort required.

Cons

- The benefits of Raw may not be as significant for applications with minimal ILP or limited parallelism.

- Implementing and optimizing software for Raw may require a steep learning curve due to its unique architecture and specialized compilers.

- While Raw can achieve impressive performance gains, it may require a larger number of tiles for certain applications, potentially impacting resource utilization and efficiency.

Takeaways

Raw demonstrates the significance of architectural innovation in tackling emerging challenges like wire delay and maximizing processor performance. Its customizable hardware and software provide adaptability to diverse application needs. Specialized compilers and parallel processing techniques are pivotal in optimizing performance for Raw-based applications. Additionally, Raw’s scalability allows for efficient handling of various workloads, making it suitable for a wide array of applications. The use of a replicated tile design streamlines development processes, leading to faster project completion and reduced effort.

Additionally, the design allows for connecting up to 64 raw chips in any rectangular mesh pattern, forming virtual Raw systems with up to 1024 tiles. In the future, researchers suggest utilizing this capability by employing 100 tiles, with certain tiles dedicated to prefetching, gathering data from neighboring tiles, emulating other instructions, or implementing traditional hardware structures.

References

- M. Taylor, J. Kim, J. Miller, D. Wentzlaff, F. Ghodrat, B. Greenwald, H. Hoffman, P. Johnson, J.-W. Lee, W. Lee, A. Ma, A. Saraf, M. Seneski, N. Shnidman, V. Strumpen, M. Frank, S. Amarasinghe, and A. Agarwal, “The raw microprocessor: a computational fabric for software circuits and general-purpose programs,” IEEE Micro, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 25–35, 2002.