Research Paper Review: MANIC - A Vector-Dataflow Architecture for Ultra-Low-Power Embedded Systems

In this paper, the authors present MANIC, a novel architecture tailored for the ultra-low-power sensor domain. MANIC achieves high energy efficiency while retaining programmability and generality. Its key feature is vector-dataflow execution, which enables it to capitalize on dataflows in sequences of vector instructions, thereby optimizing instruction fetch and decode across a vector of operations. MANIC minimizes expensive vector register file accesses by directly forwarding values from producers to consumers and strategically schedules code to avoid unnecessary register writes. Across seven benchmarks, MANIC demonstrates an average energy efficiency improvement of 2.8\(\times\) compared to a scalar baseline, outperforming a vector baseline by 38.1% and approaching an idealized design by 26.4%.

Paper Summary

The rise of small, widely distributed ultra-low-power sensor systems enables new applications. However, existing systems for these tasks are inefficient, necessitating highly energy-efficient computer architectures.

As sensor workloads become more complex, devices collect and process data for various applications. With advancements in sensor capabilities the volume of sensed data increases. This presents a challenge: How can sophisticated computations be performed on simple, ultra-low-power systems? One approach is to transmit data wirelessly to a more powerful nearby computer (at the “edge” or in the cloud) for processing. However, data transmission consumes significantly more energy per byte than sensing, storing, or computing on the data.

Given the impracticality of offloading, the alternative is to process data locally on the sensor node itself. While this reduces the energy cost of communication, it makes the device highly dependent on the energy efficiency of computation.

For a computation-intensive sensor system to be effective, it must meet two key criteria: Firstly, it must process data locally at low operating power with extremely high energy efficiency. Secondly, it must be programmable and versatile to support various applications. However, there’s a trade-off between programmability and energy efficiency. The goal is to design a highly programmable architecture that minimizes the energy costs associated with programmability by concealing microarchitectural complexity.

Existing low-power architectures exhibit limitations. These MCUs serve as general-purpose, programmable devices supporting a range of applications. However, their generality and programmability come at the cost of high power consumption, energy usage, and diminished performance. Programmability entails expenses in two main ways: Firstly, fetching instructions consumes notable energy. Without advanced microarchitectural features such as superscalar and out-of-order execution pipelines, the energy expended for instruction fetching constitutes a significant fraction of total operational energy. Secondly, accessing the register file (RF) for data supply also consumes substantial energy. Combined, instruction and data fetching account for 54.4% of the average energy consumed during execution in their experiments.

Recent research has explored two main strategies for achieving energy efficiency in computer systems. One approach involves microarchitectural specialization, which optimizes energy efficiency but sacrifices generality and programmability. Alternatively, targeting a conventional vector architecture can achieve programmable energy efficiency by spreading the cost of instruction supply across multiple compute operations. However, vector architectures tend to increase energy costs associated with RF access, especially in designs with multi-ported vector register files (VRFs), making them less energy efficient compared to fully specialized designs.

The ELM architecture distinguishes itself from previous efforts by prioritizing ultra-low-power operation, achieving high energy efficiency, and maintaining general-purpose programmability. Its efficiency is attributed to an operand forwarding network that avoids storing intermediate results and a distributed RF that offers ample register storage while mitigating unfavorable energy scaling. However, while ELM supports general-purpose programs, it does so with a high programmability cost and substantial changes to software development tools, presenting challenges for its widespread adoption. Its significant architectural and microarchitectural modifications necessitate a complete software rewrite to accommodate its unique software-managed RF hierarchy and instruction-register design.

MANIC achieves remarkable energy efficiency while maintaining its general-purpose nature and ease of programming, making it the closest to the ideal design. It simplifies programming by offering a standard vector ISA interface based on the RISC-V vector extension. The key to its high energy efficiency lies in its vector-dataflow design, which tackles the main costs of programmability. Firstly, it spreads the energy consumption of instruction supply across numerous operations through vector execution. Secondly, it reduces the high cost of VRF accesses by directly forwarding operands between vector operations in its dataflow component. MANIC enhances the vector ISA with kill annotations to eliminate unnecessary write accesses to the VRF. This architecture efficiently amortizes the energy required to track dataflow across multiple vector operations, significantly reducing VRF accesses by 90.1% on average in experiments, with minimal microarchitectural changes. Additionally, a code scheduling algorithm is devised to exploit operand forwarding, further minimizing VRF energy consumption while remaining agnostic to microarchitecture.

The implementation of MANIC is done entirely in RTL, and industry-grade CAD tools are utilized to evaluate its energy efficiency across a set of programs suitable for deeply embedded systems. Post-synthesis energy estimates demonstrate that MANIC’s energy consumption is within 26.4% of an idealized design, while still being fully versatile and introducing only minimal changes to the ISA and software development process.

Related Work

The authors have thoroughly examined existing energy-efficient architectures and integrated the best features into MANIC.

In deeply embedded and energy-harvesting systems, energy efficiency is paramount. MANIC prioritizes efficiency over microarchitectural correctness, especially in intermittent architectures, where architects should prioritize efficiency enhancements.

To reduce overhead, MANIC employs vector execution and additional techniques to minimize the cost of VRF access. It achieves this by using a single functional unit per lane, minimizing VRF ports, and avoiding unnecessary VRF access through its vector-dataflow execution model. Unlike previous approaches, MANIC transparently handles operand forwarding and register renaming to simplify software.

MANIC leverages dataflow and SIMD to improve efficiency, similar to previous architectures like RSVP and ELM. However, it distinguishes itself by hiding microarchitectural complexity from programmers and relying on the standard vector extension of the RISC-V ISA with minimal modifications.

Furthermore, MANIC identifies patterns of register liveness to eliminate RF accesses and implements register remapping at a finer granularity compared to previous approaches. It also utilizes compiler-generated hints to optimize VRF writes, a novel feature in vector designs.

Vector-Dataflow Execution

MANIC utilizes the vector-dataflow execution model to achieve two primary objectives. Firstly, it ensures general-purpose programmability, and secondly, it operates efficiently by minimizing instruction and data supply overheads. This model incorporates three key features: vector execution, dataflow instruction fusion, and register kill points.

Vector instructions enable operations to be applied across entire vectors of input operands. This significantly reduces the energy cost associated with instruction supply and control overheads, making it a crucial aspect of MANIC’s energy efficiency.

Dataflow instruction fusion identifies groups of dependent vector instructions, allowing values to be forwarded directly between instructions within the group. This eliminates the need for accessing the costly vector register file for fetching input operands, thereby reducing the overall energy consumption during execution.

Register kill points indicate when a vector register is no longer needed for subsequent instructions, thereby eliminating the need to write its value back to the vector register file. By tagging operands with optional kill bits, MANIC can optimize register file writes based on the program’s kill points, enhancing energy efficiency without affecting programmability.

The study of core compute kernels in various sensor node applications reveals ample opportunities for exploiting vector-dataflow execution. Shorter kill distances between dependent instructions suggest that even with a reasonably small window size, MANIC can effectively capture dependencies in these kernels, making it practical and efficient for real-world applications.

In MANIC, the vector unit operates as a loosely coupled co-processor with the scalar core. Thus, synchronization between vector and scalar execution is necessary to maintain a consistent memory state. A new vfence instruction has been introduced for this purpose, which stalls the scalar core until the vector unit completes execution with its current window of vector-dataflow operations. However, programmers need to ensure the correct use of vfence to avoid data races, as compilers often struggle with alias analysis. Despite this responsibility, relying on programmers to handle vfences is practical since they are rare, consistent with common practice in architectures, and aligned with high-level programming languages’ principles.

MANIC: Ultra-low-power vector-dataflow processing

MANIC’s hardware/software interface is based on the latest revision of the RISC-V ISA vector extension. It integrates a vector unit with a single lane into a simple, in-order scalar processor core. To support vector-dataflow execution, the vector unit incorporates instruction windowing hardware and a renaming mechanism for forwarding between dependent instructions. MANIC efficiently runs programs without modifications to the ISA. With a minor ISA change, MANIC enhances efficiency by conveying register kill annotations, enabling the microarchitecture to manage registers more efficiently.

The software interface to MANIC’s vector execution engine is the RISC-V ISA vector extension, allowing RISC-V code to run efficiently on a MANIC system with minimal modifications, primarily adding vfence instructions for synchronization and memory consistency.

MANIC implements the RISC-V V vector extension with 16 vector registers, utilizing an extra bit in the register name for conveying kill annotations from the compiler to the microarchitecture. The optional compiler support runs a dataflow code scheduling algorithm to optimize register usage based on kill points.

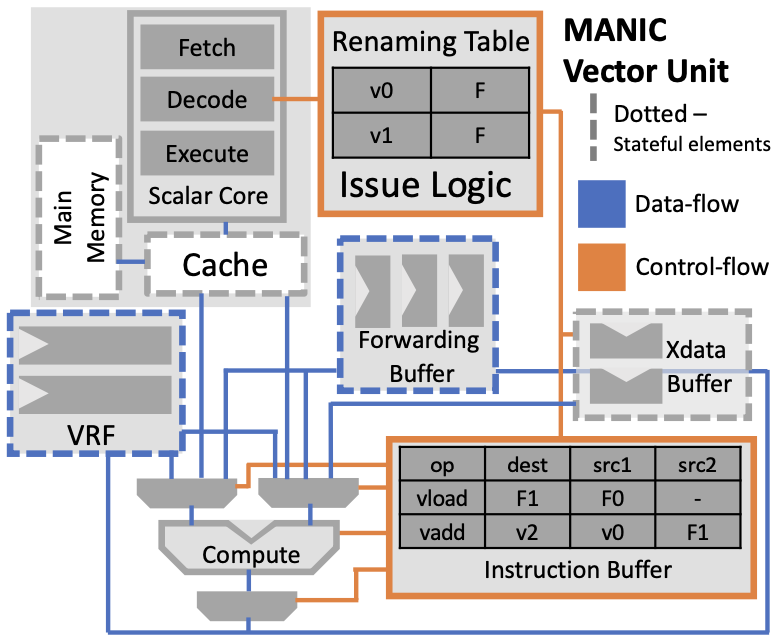

Four components are added to the base vector core in MANIC to support vector-dataflow execution: issue logic and a register renaming table, an instruction window buffer, an xdata buffer, and a forwarding buffer (Figure 1). These components work together to manage instruction execution and dependency resolution efficiently.

Structural hazards may cause MANIC to stall, primarily when buffers are full, requiring careful management to maintain efficient operation. MANIC also includes instruction and data caches, which effectively minimize main memory accesses, reducing energy consumption significantly.

To mitigate memory corruption in intermittent computing environments, MANIC assumes a hardware-software JIT-checkpointing mechanism to protect caches and ensure data integrity, with negligible energy overhead.

MANIC includes a microarchitecture-agnostic dataflow scheduling feature, facilitated by optional compiler support. This feature reorders vector instructions to bring dependent operations closer together in an instruction sequence. By doing so, MANIC enhances the likelihood of these dependent operations appearing together in one of its vector-dataflow windows. This optimization aims to minimize the distance between dependent instructions, facilitating more efficient value forwarding and reducing vector register file accesses.

Importantly, MANIC’s dataflow scheduler maintains programmability and generality, ensuring that programmers need not be familiar with the underlying microarchitecture to benefit from this optimization. This approach prevents the compiler from becoming overly dependent on specific microarchitectural parameters, enhancing its robustness.

To minimize the distance between dependent instructions, MANIC’s dataflow code scheduler considers the sum kill distance, which aggregates all register kill distances across the entire program. By minimizing the sum kill distance, the scheduler effectively reduces the average distance between dependent instructions, regardless of the specific window size of the MANIC implementation.

For small kernels with fewer than 12 vector operations, dataflow code scheduling employs brute force (exhaustive) search. However, for larger kernels like the FFT, a simulated annealing approach is used. This method randomly mutates instruction schedules while preserving dependencies to generate new valid schedules, which are accepted based on certain probabilities.

Overall, the effectiveness of minimizing the sum kill distance in eliminating register writes aligns well with explicitly exposing window size to the compiler. However, for kernels like the FFT, limitations arise due to breaks in the instruction window caused by certain operations, leading to additional vector register file writes. Addressing these limitations is a focus for future work.

Methodology

They establish a simulation framework based on Verilator to execute full applications on MANIC. This setup incorporates various components, including a modified version of Spike, adjustments to the assembler, a tailored LibC, a customized bootloader, a cache and memory simulator, and RTL for both MANIC and its five-stage pipelined scalar core. The team enhances Spike to support vector instructions for accurate RTL simulation and extends the GNU assembler to generate correct bit encodings for the RISC-V vector extension instruction set. Additionally, they develop custom LibC and bootloader to streamline startup overhead and support the architecture. A cache and memory simulator helps model timing for loads and stores, while a test harness built with Verilator enables full-application, cycle-accurate RTL simulations.

MANIC is compared against two baselines: an in-order, single-issue scalar core architecture and a basic vector architecture. Both baselines are implemented in RTL and follow a similar process to MANIC for energy and power estimation. Each baseline shares a scalar core model with MANIC and features separate instruction and data caches. While the vector baseline is similar to MANIC, it processes each vector instruction element by element and writes intermediate results to the vector register file. An idealized design, similar in datapath to MANIC but eliminating the main costs of programmability, is also considered.

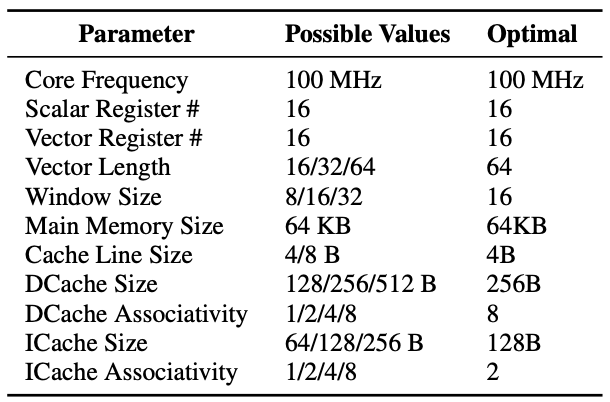

A design space exploration is conducted for the baselines and MANIC, optimizing microarchitectural parameters to minimize total energy consumption. The architectural simulations utilize parameters detailed in Figure 2.

The evaluation of MANIC encompasses seven benchmarks typical of ultra-low-power computing. These benchmarks include 2D FFT, dense and sparse matrix-matrix multiply (DMM and SMM), dense and sparse matrix-vector multiply (DMV and SMV), and dense and sparse 2D convolution (DConv and SConv). Variants of each benchmark are written, including versions utilizing SONIC for safe execution on an intermittent system, plain C versions, vectorized plain C versions, and vectorized plain C versions scheduled using MANIC’s dataflow code scheduler. The algorithms remain consistent across plain-C, vectorized plain-C, and scheduled versions, except for FFT, where the plain-C implementation uses the Cooley-Tukey algorithm, while the vectorized versions perform a series of smaller FFTs leveraging the vector length and then combine these small FFTs for the output.

Results

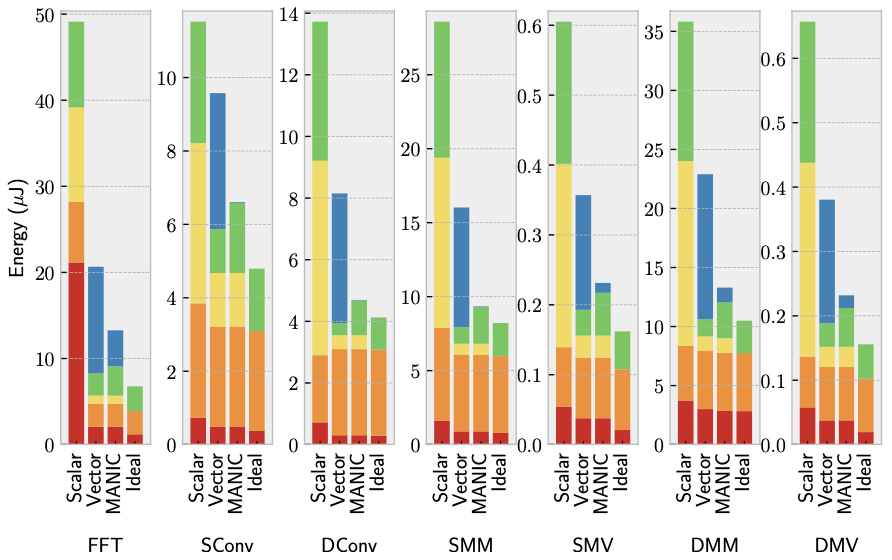

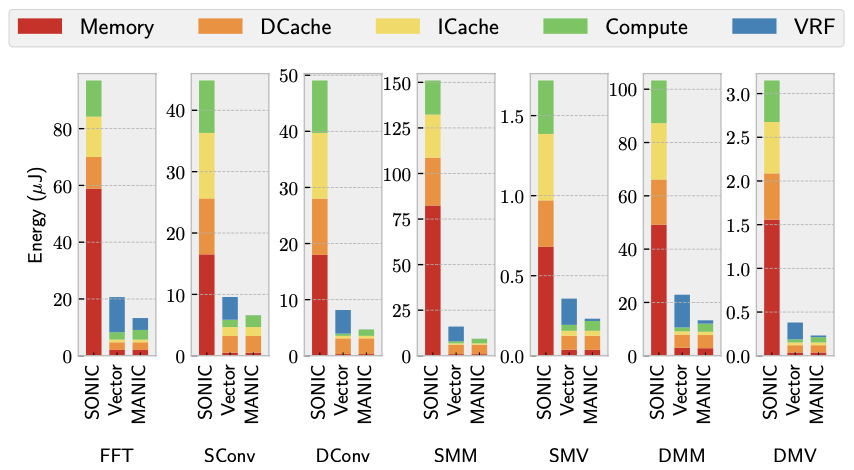

Figure 3 demonstrates MANIC’s energy efficiency by comparing full-system energy consumption across seven workloads for various architectures. The comparison between the scalar baseline, vector baseline, and MANIC indicates that MANIC consumes less total energy than either baseline. On average, MANIC reduces total energy consumption by 2.8 times and up to 3.7 times compared to the scalar baseline. These results likely underestimate MANIC’s improvement over contemporary commercial off-the-shelf systems, as the scalar baseline is modeled using 45nm technology, which consumes less energy than typical commercial offerings implemented in 130nm technology. Compared to the vector baseline, MANIC reduces energy consumption by 38.1% across all applications, with a minimum reduction of 30.9% for sparse convolution.

Comparing MANIC to the idealized design in Figure 3 illustrates MANIC’s performance relative to a design that eliminates energy costs associated with instruction and data supply. In the idealized design, memory’s energy cost dominates. MANIC’s energy consumption is within 26.4% of the ideal, indicating that the energy cost of programmability and generality in MANIC is low and approaches that of the ideal design.

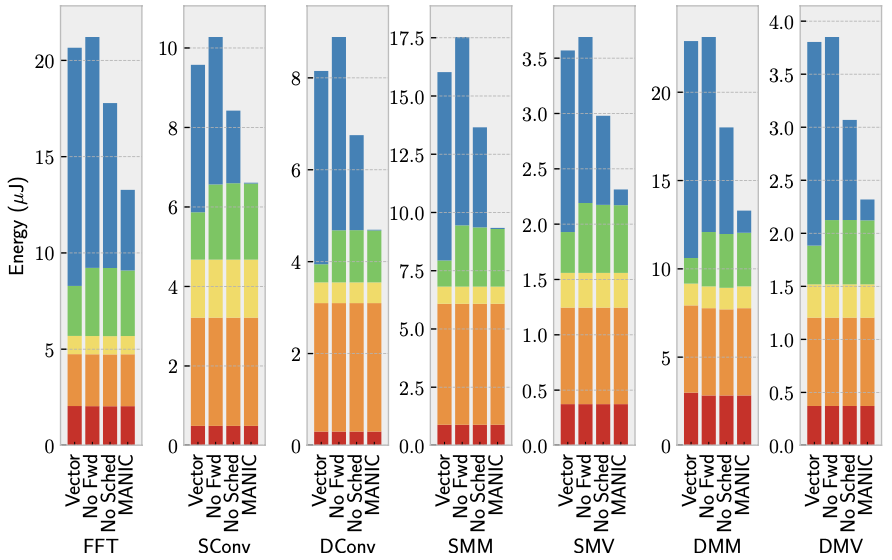

Figure 4 displays MANIC’s sensitivity to various optimizations. The second bars represent MANIC with forwarding disabled. Compared to the vector baseline (first bars), MANIC without forwarding only incurs a minor energy overhead of less than 5% due to its microarchitectural additions, such as the instruction and forwarding buffers.

The third bars in Figure 4 depict MANIC with dataflow code scheduling disabled, meaning no kill annotations are used and fewer opportunities for value forwarding exist. Despite this, MANIC still reduces energy compared to the vector baseline because forwarding effectively eliminates vector register reads. On average, MANIC’s forwarding without code scheduling reduces total energy by 15.5% over the vector baseline.

Comparing these bars to MANIC (last bars) reveals that code scheduling enhances MANIC’s forwarding by eliminating vector register writes and further reducing reads. On average, scheduling improves energy efficiency by 26% compared to without scheduling, and for dense and sparse convolution, MANIC can eliminate all vector register file accesses.

To evaluate the potential performance of MANIC under intermittent execution on an energy-harvesting system, a comparison is made with SONIC. Results depicted in Figure 5 show the performance of SONIC, the scalar baseline running plain C, and MANIC. MANIC demonstrates a significant superiority over SONIC, with an average improvement of 9.6 times. This is attributed to MANIC’s hardware support for JIT-checkpointing of architectural state before power failure, while SONIC relies on increased accesses to the icache, dcache, and main memory for software-based checkpointing. Scalar with JIT-checkpointing exhibits a 3.5 times greater efficiency than SONIC. It is noted that SONIC’s dcache operates as write-through to maintain consistency with main memory, necessitating flushes after every store for correctness.

The scalar baseline executes an average of 10.6 times more instructions and takes 2.5 times more cycles compared to both the vector baseline and MANIC. MANIC and the vector baseline have similar instruction and cycle counts since vector dataflow execution doesn’t require additional cycles. The scalar baseline expends 54.4% of its energy on instruction fetch and register file access, representing the costs of programmability. Theoretically, eliminating instruction supply and register file energy from the scalar baseline could achieve a 2.2 times reduction in energy. However, MANIC achieves a 2.8 times decrease. MANIC runs fewer instructions and effectively eliminates the need for certain scalar instructions in inner-loop nests. For instance, a single addition for address arithmetic in MANIC can replace dozens of additions in the scalar baseline.

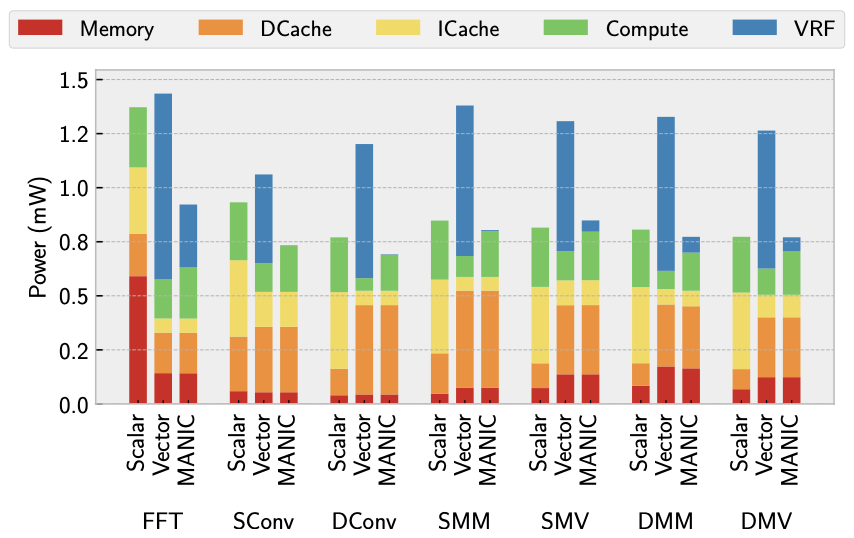

Figure 6 illustrates the average power consumption in milliwatts (mW) for the scalar and vector baselines, along with MANIC. On average, MANIC consumes 10% less power than the scalar baseline. In contrast, the vector baseline exhibits a 29.5% higher power consumption than the scalar baseline.

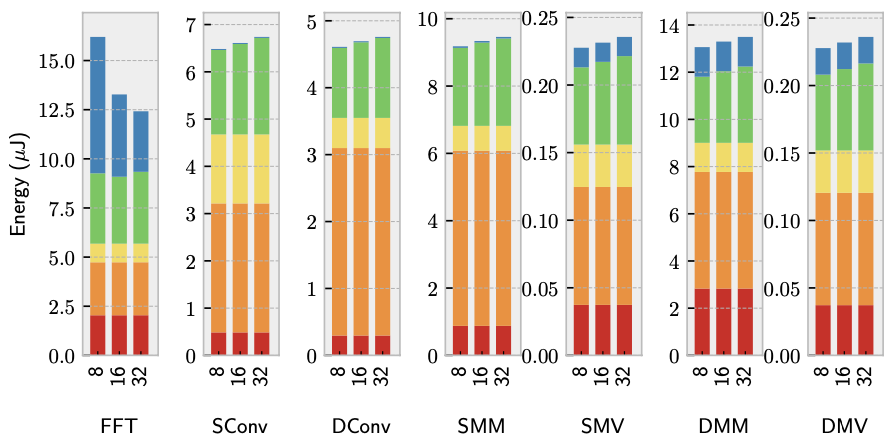

Figure 7 indicates that larger window sizes incur only a minor energy cost but offer notable enhancements to kernels capable of utilizing the additional length. Excluding FFT, optimal results are obtained with a window size of 8. However, for FFT, window sizes of 16 or 32 prove beneficial. This is attributed to FFT’s ability to forward values across loop iterations, enabling a window to encompass multiple iterations and unveil additional dataflow opportunities. It’s important to note that the static code analysis conducted by the researchers only considers a single loop iteration and thus does not capture this phenomenon.

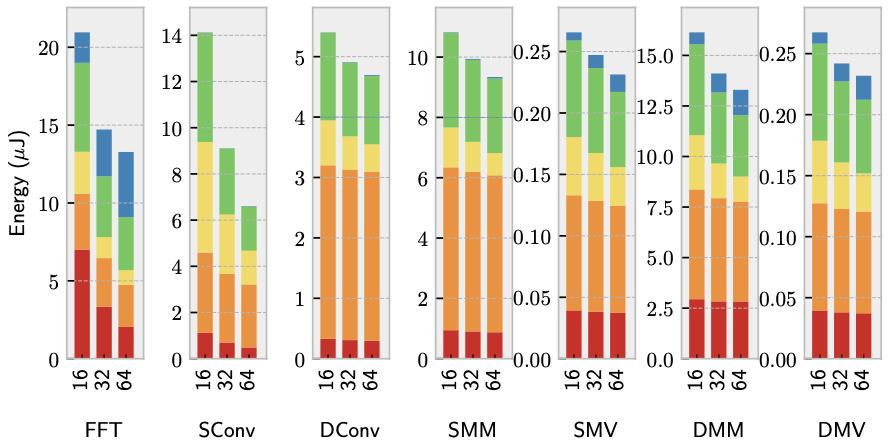

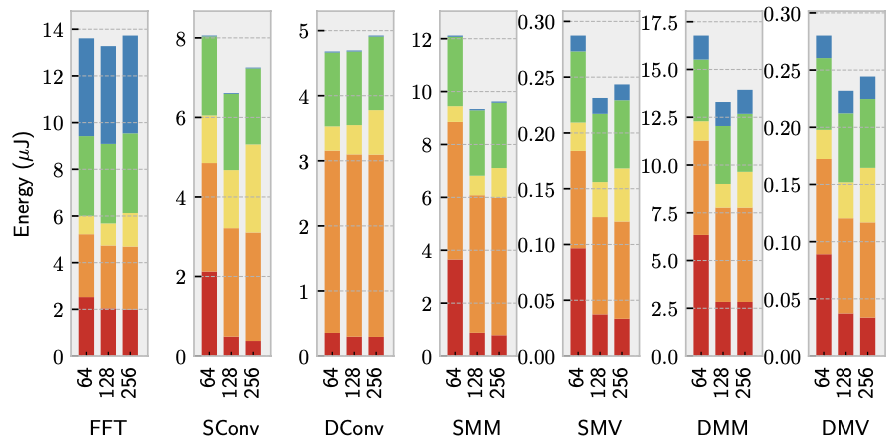

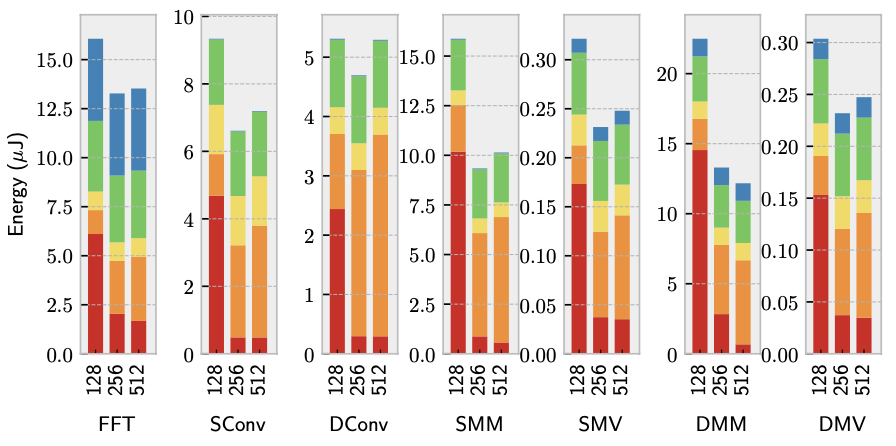

Figure 8 demonstrates that energy consumption decreases with longer vector lengths. Despite the higher access energy associated with a larger Vector Register File (VRF), forwarding reduces 90.1% of total VRF accesses, making longer vector lengths advantageous. However, the benefit diminishes as the proportion of energy allocated to instruction supply decreases relative to the total energy. The researchers capped the vector length at 64 in their experiments due to certain applications, such as FFT, being optimized for vector lengths of 64 or less. This limitation is artificial, and the researchers intend to explore even larger vector lengths in future research.

Figure 9 demonstrates the necessity of a relatively small instruction cache. The findings indicate that a very small instruction cache leads to inefficiency, as it requires frequent accesses to main memory. Conversely, an excessively large cache is unnecessary to capture instruction access locality and achieve significant energy efficiency gains. An instruction cache size of 128 bytes proves to be adequate for most benchmarks, and further increasing the size appears to have diminishing returns due to higher access energy costs.

Figure 10 indicates that, in general, a cache size of 256 bytes is sufficient. A cache that is too small results in additional misses and more frequent accesses to main memory. For most benchmarks, except dense matrix multiplication, there is no energy reduction observed for the largest cache size of 512 bytes. In fact, there may be a slight increase in energy consumption due to higher access energy and leakage. Although dense matrix multiplication still shows energy improvement for the largest cache size, the improvement is marginal compared to the enhancement between 128 bytes and 256 bytes. This suggests that most of the benefit has been achieved at the 256-byte cache size.

Critical Review

Pros

- The paper extensively analyzes existing energy-efficient architectures and incorporates their optimal features into MANIC.

- The paper offers a thorough and comprehensible overview of the MANIC architecture.

- MANIC offers a significant advancement in energy efficiency without sacrificing programmability or generality.

- Despite its specialized architecture, MANIC maintains programmability through a standard RISC-V ISA interface, enabling developers to write code without significant changes to their workflow.

- The paper provides insights into the practical implications of MANIC’s architecture by evaluating its performance across a range of benchmarks representative of real-world applications.

Cons

- While MANIC’s energy efficiency is compared to scalar core architectures and an idealized design, additional comparisons with other state-of-the-art low-power architectures could provide more insights into its competitiveness in the field.

- The paper lacks a detailed explanation of how they precisely calculated the “Ideal” architecture. However, they assert that MANIC closely resembles it.

Takeaways

This paper introduces MANIC, an ultra-low-power embedded processor architecture that achieves remarkable energy efficiency while maintaining programmability and generality. MANIC operates efficiently through its vector-dataflow execution model, where dependent instructions forward operands within a short window based on dataflow principles. This approach reduces control overhead and avoids costly reads from the vector register file. Additionally, simple compiler and software support help minimize vector register file writes in a microarchitecture-agnostic manner. MANIC’s microarchitecture implementation incorporates vector-dataflow efficiently with minimal hardware additions, while still providing a standard RISC-V ISA interface. Compared to a scalar core, MANIC is, on average, 2.8 times more energy-efficient and comes within 26.4% of an ideal design that eliminates all programmability costs. These findings demonstrate that MANIC’s vector-dataflow model is achievable and approaches the energy efficiency limit for an ultra-low-power embedded processor.

References

- G. Gobieski, A. Nagi, N. Serafin, M. M. Isgenc, N. Beckmann, and B. Lucia, “Manic: A vector-dataflow architecture for ultra-low-power embedded systems,” in Proceedings of the 52nd Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, ser. MICRO ’52. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019, p. 670–684. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/3352460.3358277