Research Paper Review: HAAC

This paper introduces HAAC, a novel garbled circuits accelerator and compiler, to make privacy-preserving computation more feasible. HAAC is a hardware-software co-design focusing on simplicity and efficiency in hardware, while leveraging program understanding in the compiler for optimized instruction schedules and data layouts. This approach maintains ASIC performance without sacrificing versatility. Key insights include expressing GCs programs as streams for hardware simplification and utilizing a scratchpad to track data reuse, eliminating the need for expensive hardware-managed caches. Evaluation with VIP-Bench shows an average speedup of 589\(\times\) with DDR4 (2,627\(\times\) with HBM2) in just 4.3mm\(^2\) of area.

Paper Summary

Privacy and security are increasingly crucial, prompting the development of new methods for robust data protection. One emerging approach is privacy-preserving computation (PPC), offering both confidentiality and user control. Confidential computing allows data computation while encrypted, ensuring service providers can’t access sensitive information. Some techniques, like secure multi-party computation, enable users to dictate data usage. However, high computational overheads limit widespread adoption of strong PPC methods. Novel hardware solutions are needed to address these challenges and enable private computing on a larger scale.

Among various PPC techniques, this paper focuses on garbled circuits (GCs). Each technique has its strengths and weaknesses, suggesting a future where multiple methods are combined to overcome limitations. The goal here isn’t to debate the superiority of GCs over other techniques, but to demonstrate how hardware acceleration can significantly reduce GCs’ performance overheads, making their benefits more accessible.

GCs offer robust confidentiality and data control, supporting arbitrary computation. They’re crucial for applications like private neural inference (PI), where non-linear layers such as ReLU are involved. However, GCs pose significant performance challenges, especially in hybrid protocols for PI. Recent studies highlight GCs acceleration as vital for faster PI, yet they face considerable overheads. For instance, across eight VIP-Bench benchmarks, GCs are on average 198,000 times slower than plaintext.

Several factors contribute to GCs’ high overhead. Firstly, each GC gate requires substantial computation, involving cryptographic functions like AES. For example, a simple Boolean AND gate may require multiple AES calls and key expansions. Secondly, functions in GCs must be expressed as Boolean logic, leading to a large number of gates for even simple tasks like sorting. Lastly, GCs are data-intensive, with inputs and outputs represented as ciphertexts and each gate involving unique cryptographic constants.

GCs offer two advantageous properties for efficient hardware acceleration. Firstly, their complex computations can be effectively implemented in custom logic hardware, leveraging parallelism within gates to enhance performance. Secondly, GCs programs are fully determined at compile time, allowing for complete software understanding of their behavior, known as data obliviousness. This enables hardware-software co-design, where programmable hardware executes GCs programs efficiently with compiler-organized data movement and instruction scheduling. This approach optimizes gate computations by parallelizing them across gate processing hardware and streaming data on-/off-chip to mask movement latency, reminiscent of Very Long Instruction Word (VLIW) architecture. This simplicity in hardware design maximizes area for actual computation. Other approaches like fixed-logic ASICs limit functional support, systolic arrays and vectors constrain data layout and computation order, and dataflow methods are wasteful as compilers can handle scheduling without costly structures.

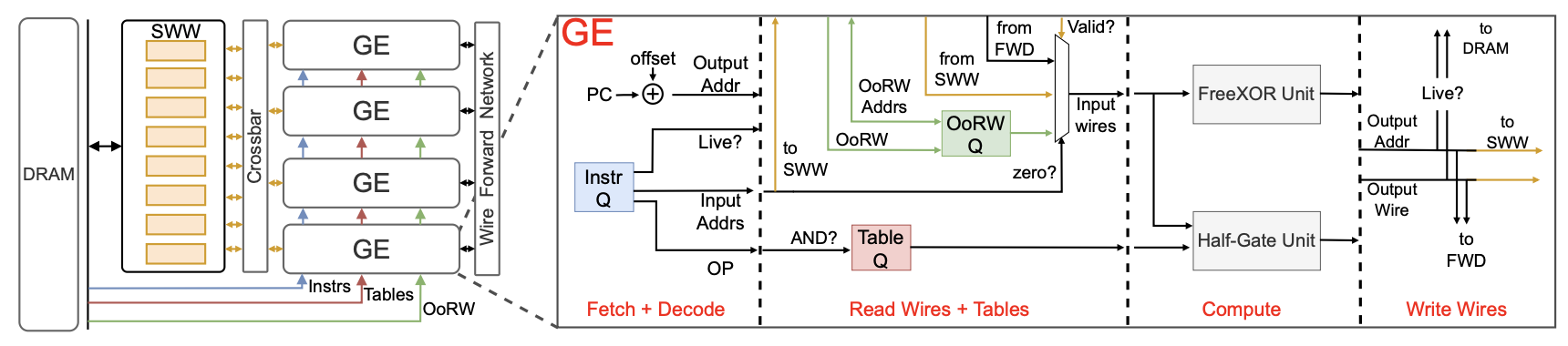

This paper introduces HAAC, a novel co-design approach to accelerate GCs by harnessing their computational properties (Figure 1). HAAC comprises a compiler, ISA, and hardware accelerator, working together to greatly enhance GCs’ performance and efficiency. HAAC accelerates individual gate execution with a specialized component called the gate engine (GE). While GEs offer high performance potential, effectively utilizing gate parallelism and managing data (operands, constants, instructions) poses challenges in maintaining hardware efficiency. A key insight is that the compiler, aided by hardware support, can represent GCs as multiple streams. This enables leveraging instruction-level parallelism to enhance intra/inter-GE processing efficiency. By organizing events, instructions, and constants into streams and using queues to deliver them to each GE, HAAC optimizes gate execution. Managing gate inputs and outputs, referred to as wires, poses additional complexity due to their non-linear nature. Instead of inefficiently streaming all wires on-/off-chip, HAAC introduces the sliding wire window (SWW) and wire renaming techniques. The SWW acts as a scratchpad memory storing a dynamic range of wires, while wire renaming organizes gate output wire addresses sequentially based on program order. Together, SWW and wire renaming minimize off-chip accesses by filtering recently used wires, providing cache-like performance benefits with the efficiency of a scratchpad. Despite these optimizations, some off-chip accesses, termed Out-of-Range (OoR) accesses, still occur due to limited capacity. HAAC addresses this issue by streaming OoR wires on-chip through an OoR wire queue, guided by the compiler’s knowledge of when and which wires will be OoR. These optimizations enable complete decoupling of gate execution and off-chip accesses, facilitating efficient overlap and improving overall performance.

Results

Compiler Optimizations

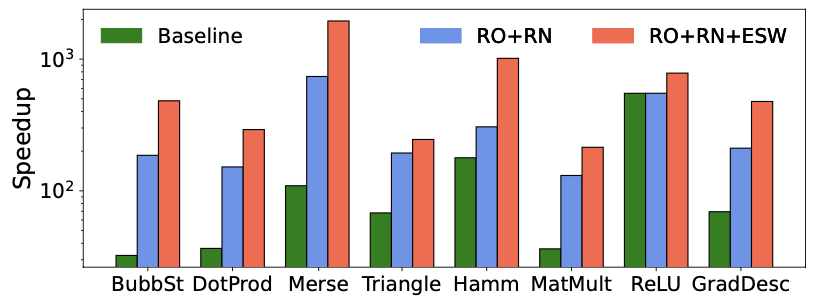

In this experiment, an Evaluator HAAC with 16 GEs, a 2MB SWW, and DDR4 is utilized. The results are presented in Figure 2, showing speedup relative to the original EMP program (baseline) running on the CPU. Green bars indicate HAAC’s speedup using baseline instruction schedules, while blue bars show the performance after full reordering and renaming optimizations. Red bars include eliminating spent wires (ESW) and are discussed subsequently.

The baseline bars (green) reveal that even with the baseline program, HAAC achieves commendable results, with an average speedup of 82.6\(\times\) compared to the CPU. After the compiler fully reorders and renames the baseline program (blue bars), an additional average speedup of 3.1\(\times\) over the baseline is observed, showcasing the effectiveness of increasing parallelism and better utilizing GEs. Reordering and renaming are grouped together as renaming is essential for the effectiveness of SWW. However, full reordering and renaming do not accelerate ReLU due to already significant parallelism in the baseline program.

It is noteworthy that while on a CPU, garbling is 11.9% slower than evaluation, the HAAC Garbler is only 0.67% slower than the HAAC Evaluator across all benchmarks. Therefore, a higher HAAC speedup is expected for Garbler, but here the report conservatively focuses on Evaluator speedup.

Optimizing Off-Chip Memory Traffic

The performance benefits of Eliminating Spent Wires (ESW) are analyzed in this section. The red bar in Figure 2 indicates the performance of full reordering with ESW. By adding the live bit to instructions, it is observed that an average of 84% of wires can be saved from being stored back to off-chip memory, resulting in significant bandwidth savings. This reduction in off-chip storage leads to an average speedup of 2.1\(\times\) compared to full reordering and renaming alone. The Hamming-Distance benchmark demonstrates the most speedup, reaching 3.3\(\times\), aligning with expectations. This performance gain from ESW also suggests that the reordered programs are memory-bound, and thus ESW provides a speedup over full reordering.

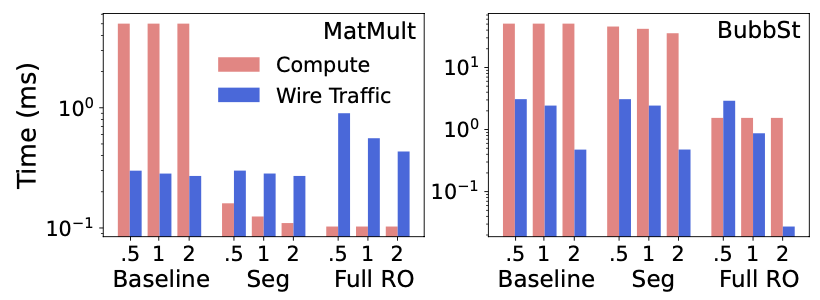

Segment Reorder is introduced as a compromise between baseline and full reordering to address limitations in wire access range within a limited instruction window. The comparison of wire traffic between baseline and segment reordering approaches, with segment reordering reducing wire traffic by an average of 5.0\(\times\) compared to full reorder, particularly benefiting benchmarks such as MatMult.

Figure 3 further analyzes the performance of different reorderings using representative benchmarks: Matrix Multiplication (MatMult) and Bubble Sort (BubbSt). Segment reordering proves highly effective for MatMult, balancing compute parallelism and memory bandwidth, while improving compute time without significantly increasing wire traffic. In contrast, BubbSt demonstrates that baseline wire traffic is not always optimal due to long chains of dependent instructions. Full reorder improves both compute time and wire traffic by maximizing on-chip wire reuse through the SWW.

In practice, both segment reordering and full reorder can be evaluated, and the best-performing optimization deployed, as performance is deterministic.

Parallel GE Execution and Speedup Over Software

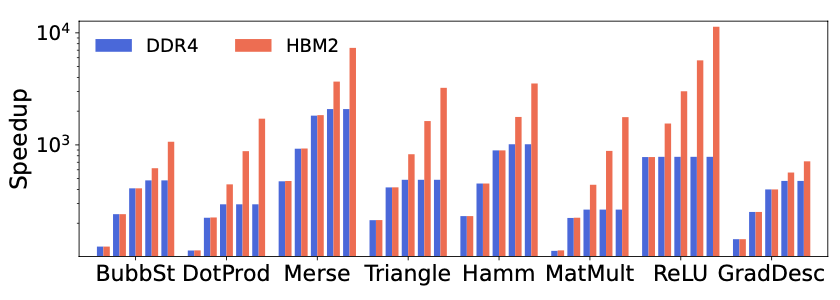

Figure 4 illustrates the speedup relative to CPU performance. The evaluation scales GEs from 1 to 16 and uses a 2 MB SWW. Two types of DRAM are considered: DDR4 for fair comparison with the CPU and HBM2 to gauge HAAC’s benefit from advanced memory technology. With DDR4, benchmarks employ either segment or full reordering for better performance. When using HBM2, full reordering is used across all benchmarks to maximize ILP and available bandwidth.

In most cases, performance scales well initially when increasing the number of GEs, but designs can saturate DDR4 bandwidth and become memory-bound, indicated by plateauing blue GE speedup bars. With HBM2, performance continues to scale across the considered range of GEs. When a red bar exceeds its corresponding blue bar, it suggests HAAC is limited by DDR4’s memory bandwidth, and HBM2 can aid in further scaling performance. With HBM2, the maximum speedup from one to sixteen engines is 15.5\(\times\) (for MatMult), with a geomean speedup of 12.3\(\times\) for the Evaluator (the Garbler shows similar performance). Gradient-Descent and Bubble Sort show constrained performance scaling due to their lack of ILP.

Regardless of the design used, HAAC demonstrates significant benefits over CPU implementation. Using a single GE with HBM2, HAAC achieves a maximum speedup of 779\(\times\) (ReLU) and a geomean of 213\(\times\) across all benchmarks. Scaling to a highly parallel 16 GEs design, a geomean speedup of 2,616\(\times\) and a maximum speedup of 11,330\(\times\) (ReLU) are observed, assuming HBM2 and full reordering for all benchmarks.

Area, Power, and Energy Analysis

| Component | Area (mm\(^2\)) | Power (mW) |

|---|---|---|

| Half-Gate | 2.15 | 1253 |

| FreeXOR | 9.51E-04 | 0.321 |

| FWD | 1.80E-03 | 0.255 |

| Crossbar | 7.27E-02 | 16.6 |

| SWW (SRAM) | 1.94 | 196 |

| Queues (SRAM) | 0.173 | 35.5 |

| Total HAAC | 4.33 | 1502 |

| HBM2 PHY | 14.9 | 225 (TDP) |

Table 1: A breakdown of HAAC chip area and average power

Table 1 displays the area and power figures for a 16 GEs design with a 2 MB SWW and 64 SWW banks. The design utilizes a 64 KB SRAM for table, instruction, and OoRW queues, along with a single HBM2 PHY. In HAAC, most of the chip area is allocated to the GE, specifically the Half-Gate and SWW. The total area for HAAC is 4.3 mm\(^2\) in 16nm technology. Considering its compact footprint, HAAC is assumed to be used as an IP in a larger SoC, thus the PHY would be shared, and the focus is on reporting HAAC IP area. All figures are included to inform users interested in standalone chips about the relatively high cost of the HBM2 PHY compared to HAAC’s size.

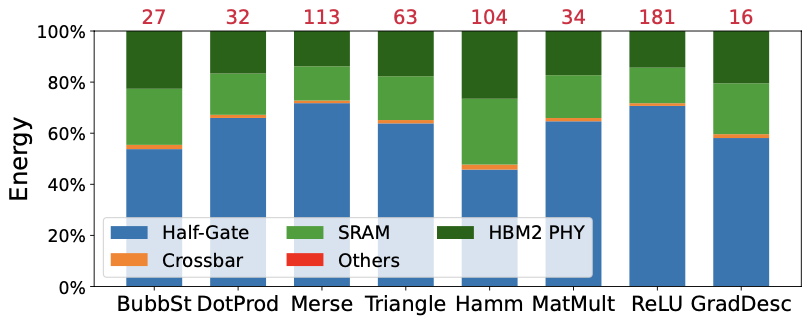

The average power dissipation across benchmarks is 1.50W (1.73W including HBM2), resulting in a power density of 0.35W/mm2. The moderate power dissipation is attributed to the high switching rate of the cryptographic circuits and SWW frequency. Figure 5 illustrates the energy consumption breakdown for each fully reordered benchmark. The Half-Gate accounts for most of the energy consumption, averaging 61% across all benchmarks. In comparison, the CPU is significantly slower and higher power, dissipating an average of 25W across benchmarks. The red text above each bar indicates HAAC’s energy efficiency improvement over the CPU baseline, averaging 53,060\(\times\) more energy efficient than the CPU.

Comparing to Plaintext

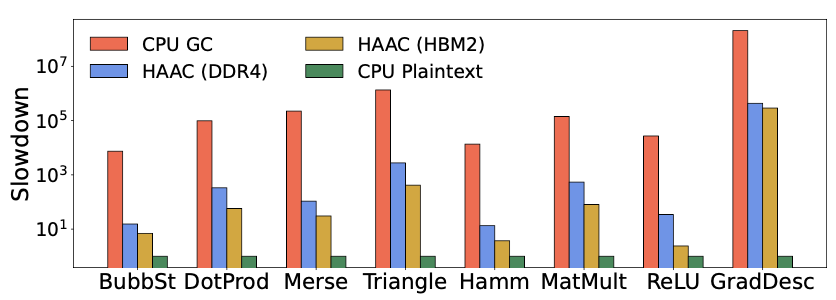

While understanding speedup relative to a software implementation is informative, the true measure of performance in PPC lies in its comparison to non-encrypted plaintext. Figure 6 illustrates the runtime comparison of HAAC (using both DDR4 and HBM2) to native, plaintext C++ and EMP (CPU GC). Secure computing inevitably incurs a cost, especially with larger data sizes and increased work-per-function, affecting all PPC methods. Recognizing this cost is crucial in determining when and where to deploy secure computing. However, the results are promising.

Compared to CPU-run GCs, a HAAC accelerator with DDR4 achieves a geomean speedup of 589\(\times\). This figure assumes the same off-chip bandwidth as the benchmarked CPU and is reported at the beginning of our paper. With HBM2, a HAAC accelerator achieves a geomean speedup of 2,627\(\times\), assuming the best reordering scheme for each benchmark, while experiencing a geomean slowdown compared to plaintext of 76\(\times\). GradDesc exhibits particularly slow performance due to the high cost of securely performing floating point operations with GCs, as Boolean circuits are complex, unlike the quick processing capability of plaintext CPUs using native instructions. However, when considering only integer benchmarks, the geomean slowdown compared to plaintext is reduced to 23\(\times\). Overall, HAAC significantly reduces most of the performance overheads of GCs, making the slowdown much more manageable. Additional compiler optimizations, higher levels of parallelism (e.g., multiple HAAC cores), and processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques may further narrow this performance gap.

Comparing to Related Work

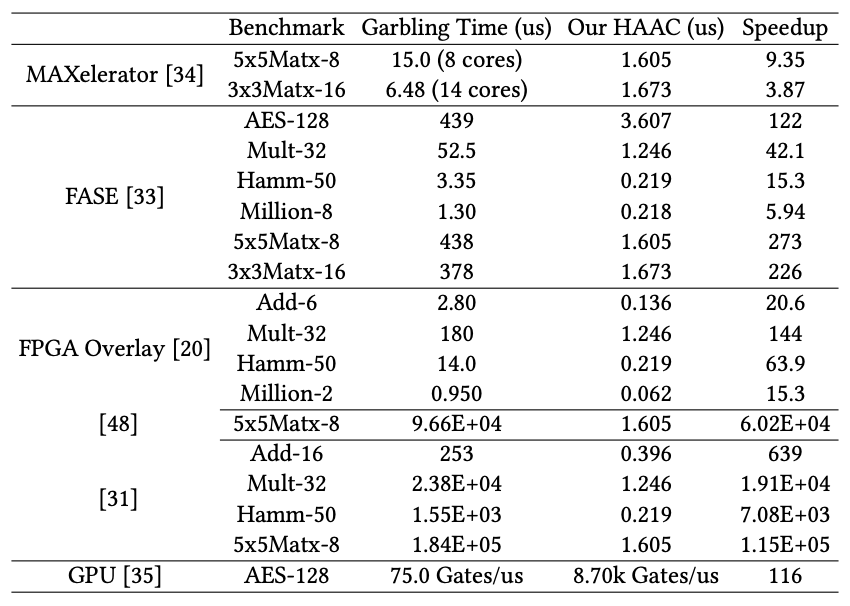

The conclusion offers a comparison between HAAC and previous work, noting that earlier approaches often utilized less secure setups involving AES or SHA-1. Despite challenges in comparison due to differences in algorithms and hardware, the authors provide a comparison to acknowledge prior work and offer insight into previous achievements.

Figure 7 illustrates HAAC’s superiority over previous methods like FASE, MAXelerator, and FPGA Overlay, particularly evident for substantial workloads such as AES and matrix multiplication. FASE, which bears the closest resemblance to HAAC, differs in compiler optimization and memory handling. While FASE focuses on gate fanout optimization, HAAC prioritizes ILP and leverages GCs input/output patterns to reduce conflicts and enhance efficiency. When comparing hardware performance, HAAC significantly outperforms FASE, especially apparent with larger workloads.

Other implementations on GPUs exhibit considerably lower performance and higher power and area requirements compared to HAAC. Despite their ability to garble millions of gates per second, GPUs fall short in performance and efficiency compared to HAAC, which achieves billions of gates with lower power and area requirements.

Critical Review

Pros

- HAAC presents a novel hardware-software co-design approach for accelerating privacy-preserving computation (PPC), addressing the growing importance of privacy and security in system design.

- HAAC achieves high efficiency in terms of both performance and power consumption, making it a promising solution for practical deployment.

Cons

- While HAAC demonstrates significant improvements for certain workloads, its effectiveness may vary depending on the specific application and workload characteristics.

Takeaways

The paper presents the effectiveness of co-design in accelerating garbled circuits, introducing the HAAC approach. HAAC integrates a compiler, ISA, and microarchitecture to enhance the performance and efficiency of garbled circuits while maintaining versatility and programmability. By assigning tasks between hardware and software, it navigates the complexities often found in high-performance hardware design. The contributions include the development of a gate engine (GE) to streamline gate computations, customized memory structures for GCs data, a compiler for efficient high-level code translation, and the Sliding Wire Window (SWW) for optimized wire reuse without tagging logic. While the paper primarily focuses on garbled circuits, the authors suggest that HAAC’s VLIW-style co-design approach could be applicable to other data-oblivious workloads, potentially expanding its influence.

References

- J. Mo, J. Gopinath, and B. Reagen, “Haac: A hardware-software co-design to accelerate garbled circuits,” in Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, ser. ISCA ’23. ACM, Jun. 2023. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3579371.3589045