Research Paper Review: Graphicionado

The paper details the development of Graphicionado, a specialized accelerator designed for efficient graph analytics. The researchers optimized both data processing and memory usage, capitalizing on inherent parallelism in graph tasks. Graphicionado enhances the vertex programming paradigm, enabling various graph analytics applications to run on the same platform with adaptable blocks. The study elaborates on Graphicionado’s pipeline design and its effectiveness in addressing inefficiencies observed in general-purpose CPUs. Results indicate Graphicionado achieves a 1.76-6.54\(\times\) speedup and consumes 50-100\(\times\) less energy compared to a leading software-based graph analytics framework running on a 16-core Haswell Xeon processor with 32 threads.

Paper Summary

In the era of big data, there’s been a renewed interest in developing graph analytics applications to uncover new solutions and insights. This resurgence prompted advancements in both software and hardware communities. Software developers worked on more efficient graph analytics processing frameworks, while hardware specialists aimed to create hardware tailored for executing graph analytics applications more efficiently than general-purpose processors. This research focuses on leveraging the structured data movements and computation patterns inherent in graph analytics applications to enhance efficiency, as well as addressing challenges they encounter when running on traditional CPUs.

When considering graph domain accelerators, certain key characteristics must be taken into account. Graph analytics applications often encounter challenges related to memory latency or bandwidth constraints. For instance, tasks like graph traversals require numerous memory accesses relative to minimal computation. However, current general-purpose processors are not ideally suited for executing such applications efficiently. Their drawbacks include inefficient memory access granularity, ineffective on-chip memory utilization, and a mismatch in execution granularity. To address these limitations, a set of datatype and memory subsystem specializations is proposed, along with the exploitation of inherent parallelism in graph workloads, to alleviate performance bottlenecks.

This paper introduces Graphicionado, a specialized hardware pipeline tailored for graph analytics tasks, which incorporates optimizations in datatype and memory subsystems alongside configurable blocks. Additionally, the paper provides an in-depth analysis of microarchitecture optimizations designed to improve performance and energy efficiency. These optimizations focus on extracting parallelism and implementing slicing and partitioning techniques to effectively manage large-scale real-world graphs.

Background and Motivation

Software Graph Processing Frameworks

Software graph processing frameworks aim to provide users with ease of programming, improved performance, and efficient scalability for workloads. Among the different programming interfaces, vertex programming is the most popular. In this model, algorithms are expressed as operations on individual vertices and their edges, which is generally considered user-friendly but can vary significantly in implementation performance. In the vertex programming model, each vertex has a specific property updated iteratively, inspecting incoming edges from active vertices in each iteration. Process_Edge handles each edge separately, followed by Reduce to form a single value. Apply updates the vertex’s current state using the reduced value and constant vertex property. This model supports various graph algorithms and offers user-controllable parameters, such as vertex activation and convergence threshold.

Algorithms

The paper discusses four fundamental graph algorithms representing applications in machine learning, graph traversal, and graph statistics. These algorithms serve as core kernels and building blocks for many graph processing applications. Various mapping strategies exist for translating algorithms into the vertex programming model.

- PageRank (PR) calculates vertex scores based on metrics like popularity, commonly used for ranking web pages.

- Breadth-First Search (BFS) explores neighboring vertices iteratively from a starting vertex, assigning distances to each vertex connected to active vertices in each iteration, commonly employed in graph search tasks.

- Single Source Shortest-Path (SSSP) traverses a weighted graph to compute distances from a single source vertex to all others, similar to BFS but utilizing edge weights for distance calculation.

- Collaborative Filtering (CF) is a machine learning algorithm used in recommendation systems, estimating user ratings for items based on latent features, employing matrix factorization through gradient descent. CF operates on an undirected bipartite graph, where users and items form disjoint sets, and all vertices remain active throughout iterations.

Software Framework Inefficiencies

As demonstrated in prior research, many platform-optimized native graph algorithms face limitations due to memory bandwidth constraints. Additionally, software graph processing frameworks often incur inefficiencies by executing numerous instructions solely for data movement and supplying data for custom computations defining the target algorithm. For three of the above four algorithms, less than 6% of executed instructions are for custom computations, with over 94% dedicated to graph traversal and loading required arguments, leading to low energy efficiency.

Overcoming inefficiencies

To overcome inefficiencies in software frameworks, the team implemented two solutions. Firstly, they applied memory subsystem specialization and designed an on-chip storage as part of the accelerator. This on-chip storage significantly reduced communication latency and bandwidth by converting frequent and inefficient random off-chip data communication to on-chip, efficient, finer-granularity scratchpad memory accesses. Secondly, they employed data-structure-specific specialization or datatype specialization and built datapaths around processing graph analytics primitives like vertices and edges. This approach further minimized peripheral instruction overheads required for operand preparation. The team’s work demonstrates that datatype specialization, coupled with the programmable and high-performing vertex program paradigm, enables the Graphicionado pipeline to achieve a balance between specificity and flexibility while delivering exceptional energy efficiency.

Graphicionado Overview

Graphicionado is a specialized hardware accelerator designed for graph analytics algorithms. It combines the programmability and flexibility of the GraphMat software framework. Like software frameworks, Graphicionado enables users to define specific graph algorithms using three computations: Process_Edge, Reduce, and Apply. It efficiently manages data movement and communication both on-chip and off-chip to support these operations. Graphicionado addresses software framework limitations by applying specializations to the compute pipeline and memory subsystem.

Graph processing model

Graphicionado processes input graphs in a coordinate format, where vertices are listed with associated properties and edges are represented by 3-tuples indicating their source, destination, and weight. Before entering the processing pipeline, the input graph undergoes preprocessing to create an EdgeIDTable, facilitating efficient access to vertex edges. Graphicionado stores various arrays in memory, including vertex properties (VProperty), temporary properties (VTempProperty), and constant properties (VConst). During the Processing Phase, active vertices are processed, examining outgoing edges and performing user-defined computations (Process_Edge and Reduce) to update temporary properties. This phase continues until all active vertices are processed. For certain workloads like Collaborative Filtering, properties of both source and destination vertices need manipulation. In the Apply Phase, properties of all vertices are updated using the Apply function, utilizing input values from the property arrays. The ActiveVertex array tracks vertices with changed properties after this phase.

Hardware Implementation

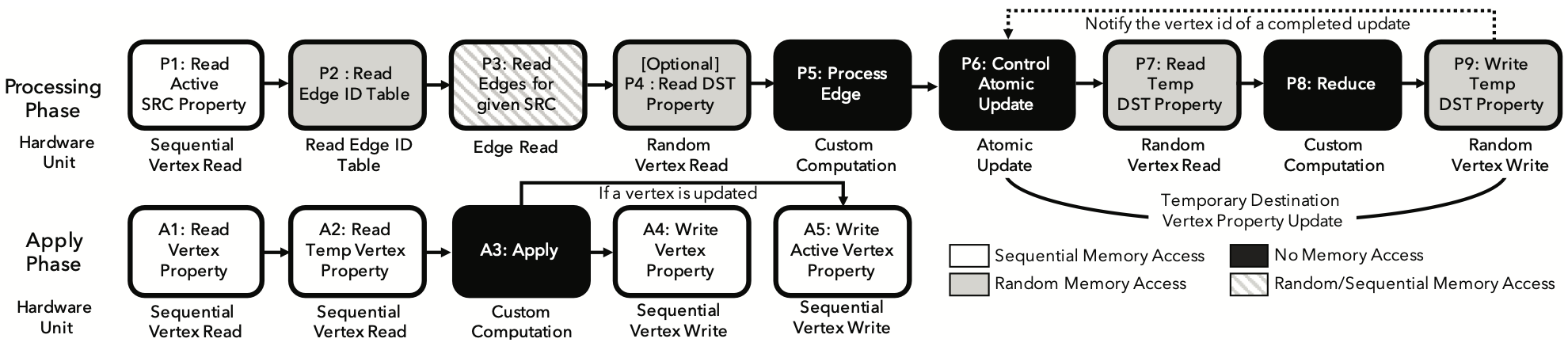

The Graphicionado pipeline, depicted in Figure 1, comprises interconnected modules facilitated by small hardware queues (4-8 entry FIFOs) for communication. These modules include:

- Sequential Vertex Read: Conducts sequential memory read accesses from a starting address, buffering one cacheline of data, and passing vertex properties individually to the output queue for consumption in subsequent pipeline stages. Used in stage P1 of the Processing phase, and A1 and A2 of the Apply phase to read

VPropertyandVTempProperty. - Sequential Vertex Write: Performs sequential memory writes from a starting address, storing data from the input queue into its internal buffer and issuing write requests to memory when the buffer is full. Used for updating

VPropertyin stage A4 andActiveVertexin stage A5 during the Apply phase. - Random Vertex Read/Write: Facilitates random reads and writes based on vertex IDs, used to read the destination

VPropertyin stage P4, read and writeVTempPropertyin stage P7 and P9. - EdgeID Read: Reads from the preconstructed

EdgeIDTablebased on a vertex ID, outputting the ID of the first associated edge. Implementations differ between base and optimized Graphicionado pipelines. - Edge Read: Performs random and sequential reads of edge data based on an

eid, examining streamed edge data for theirsrcidand fetching additional data from memory as needed. - Atomic Update: Manages destination

VPropertyupdates in three steps: readingVProperty(P7), performing a Reduce computation (P8), and writing the modifiedVPropertyback to memory (P9). Ensures atomicity for the same vertex across pipeline stages by stalling the pipeline and blocking vertex ID issuance when a violation is detected.

Additionally, Graphicionado employs three user-defined custom computations – Process_Edge, Reduce, and Apply – to express the target graph algorithm. These computations can be implemented using fully reconfigurable fabric, programmable ALUs, or fully custom on-chip implementations, with this paper utilizing the third option and constructing custom functions using single-precision floating-point adders, multipliers, and comparators.

Graphicionado Optimizations

To ensure optimal performance of the base pipeline, it’s crucial to match the throughput of each pipeline stage. This section identifies potential bottlenecks in the base implementation and introduces optimizations and extensions to address these shortcomings.

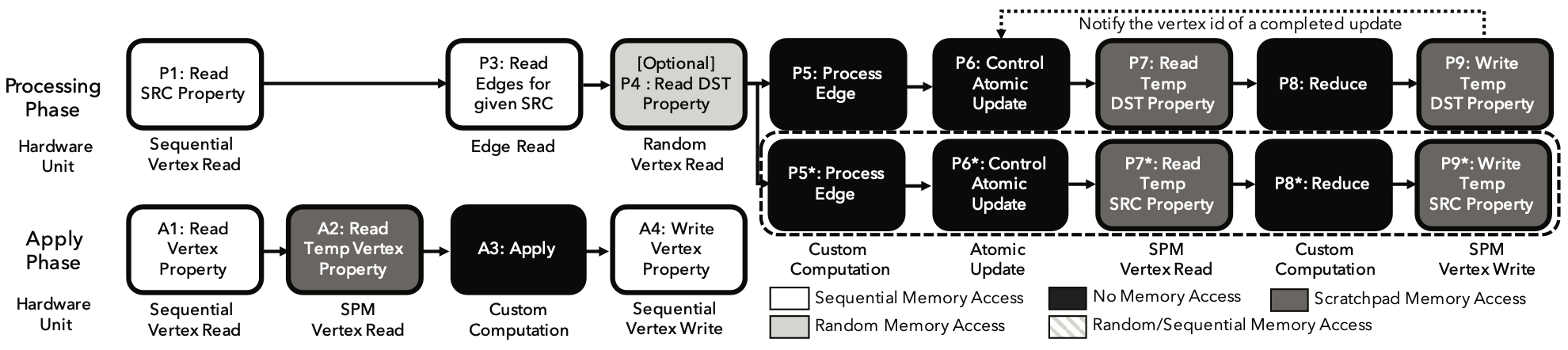

Utilizing on-chip scratchpad memory

One major bottleneck in the Graphicionado pipeline is the destination vertex update process (Fig. 1 stages P6–P9). It underperforms due to slow random memory reads and writes, as well as the inefficiency of reading and writing small vertex properties in cacheline-sized chunks, wasting off-chip memory bandwidth. Additionally, these updates require atomicity, which poses challenges when multiple updates target the same vertex. Graphicionado addresses these issues by utilizing a specialized on-chip embedded DRAM (eDRAM) scratchpad memory (Fig. 2 stages P6–P9) to store the VTempProperty array. This on-chip storage improves the throughput of random vertex reads and writes, eliminates bandwidth waste, and reduces pipeline stall time by minimizing latency.

Another potential bottleneck in the pipeline is reading the EdgeIDTable (Fig. 1 stage P2), which involves a random memory access that can stall the pipeline. To mitigate this, Graphicionado stores the EdgeIDTable data in the on-chip scratchpad memory.

Storing VTempProperty and EdgeIDTable on-chip virtually eliminates random memory accesses in the pipeline. If the on-chip memory size is insufficient, an effective partitioning scheme is employed to minimize the performance impact while maximizing storage efficiency.

Optimization for edge access pattern

Some graph algorithms, like BFS and SSSP, work with active vertex frontiers, while others, like PageRank and CF, consider all vertices as active. For algorithms such as PageRank and CF, referred to as complete edge access algorithms, all edges in the graph are accessed and processed in every iteration. In these algorithms, stage P3 in Fig. 2 sequentially reads from the edge list, eliminating random off-chip memory accesses when combined with on-chip scratchpad memory usage. A similar optimization occurs in the Apply phase, where stage A5 in Fig. 1 is removed, resulting in an optimized pipeline shown in Fig. 2.

Prefetching

With the optimizations discussed, Graphicionado now primarily relies on sequential off-chip memory accesses. Since the addresses of these accesses are independent of other pipeline sections, the implementation of next-line prefetching becomes feasible. This prefetching technique allows data to be retrieved into the accelerator before it is needed. The sequential vertex read and edge read modules (stage P1 and P3 in Fig. 2) are expanded to prefetch and buffer up to \(N\) cachelines (\(N = 4\) in the evaluation), continuously fetching the next cacheline from memory as long as the buffer is not full. This optimization effectively hides most sequential memory access latencies, thereby enabling Graphicionado to maintain high throughput.

Optimization for symmetric graphs

Most graph processing frameworks, including GraphMat, naturally handle directed graphs. In these frameworks, an undirected input graph is treated as a symmetric graph, meaning each edge (srcid, dstid, weight) has a corresponding edge (dstid, srcid, weight). While this approach works, it results in unnecessary memory accesses for algorithms like Collaborative Filtering. To reduce bandwidth consumption, Graphicionado extends its pipeline to update both source and destination vertex properties when processing edges from symmetric graphs, eliminating the need to read the same data twice. This optimization is reflected in the optimized pipeline shown in Fig. 2 stages P5–P9, where this part of the pipeline is replicated.

Large vertex property support

The current Graphicionado pipeline is designed to handle processing up to 32 bytes of vertex property data per cycle. However, when dealing with large vertex properties, such as in Collaborative Filtering where properties are 128 bytes each, they are treated as packets comprising multiple flits, with each flit containing 32 bytes. In most pipeline stages, each flit is processed without waiting for the entire packet to arrive, similar to wormhole switching. However, for custom computation stages, the pipeline waits for the entire packet data to arrive using a buffering scheme before performing computations, akin to store-and-forward switching, to maintain functionality. Proper buffering (4 flits in the case of Collaborative Filtering) ensures that the pipeline’s throughput is not significantly impacted.

Graphicionado Parallelization

With the optimizations outlined above, Graphicionado can effectively handle graph analytics workloads. However, it currently operates as a single pipeline, with its maximum throughput theoretically limited to one edge per cycle in the Processing phase and one vertex per cycle in the Apply phase. This section explores enhancing Graphicionado’s pipeline throughput further by leveraging the inherent parallelism present in graph workloads.

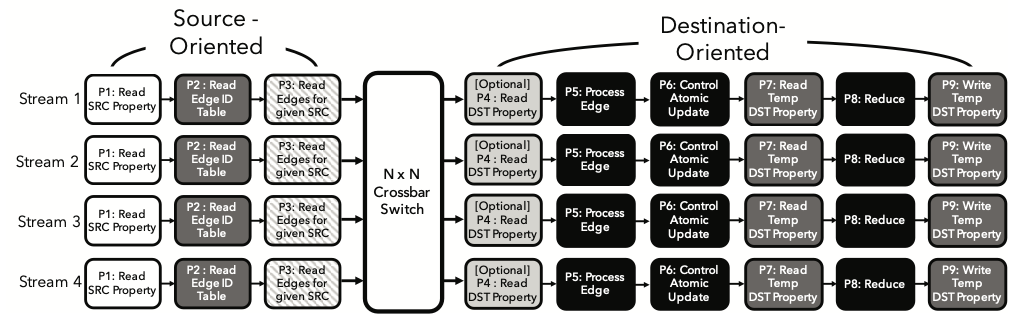

Extension to multiple streams

One way to introduce parallelism in the Graphicionado pipeline is by replicating the pipeline and assigning each replicated pipeline, or stream, to handle a portion of the active vertices. While this method is common in software graph processing frameworks to increase parallelism, it poses drawbacks in the hardware pipeline. Concurrent attempts by multiple replicated streams to access the same on-chip scratchpad location lead to performance degradation due to serialization of operations. To mitigate these access conflicts, Graphicionado divides the Processing phase into source-oriented and destination-oriented portions, corresponding to stages P1–P3 and stages P4–P9 in Fig. 1. These portions are replicated separately and connected via a crossbar switch, as depicted in Fig. 3. Each parallel stream in the source-oriented portion processes a subset of the source vertices, while those in the destination-oriented portion handle a subset of the destination vertices. The crossbar switch routes edge data based on the destination vertex id of the edge, utilizing techniques like virtual output queues to maximize throughput. The source-oriented portion reads pre-partitioned source VProperty and associated edges from memory, partitioned based on the last \(\log_2(n)\) bits of the source vertex id for \(n\) streams. Similarly, the destination-oriented portion reads pre-partitioned destination VProperty and reads/writes pre-partitioned destination VTempProperty from the on-chip scratchpad, partitioned based on the last \(\log_2(m)\) bits of the destination vertex id for \(m\) streams. This parallelization strategy ensures exclusive access to memory and scratchpad memory regions for each stream, eliminating memory access conflicts. Additionally, it simplifies the on-chip scratchpad memory design by implementing \(m\) instances of dual-ported eDRAMs for Graphicionado instead of using a single large eDRAM with \(2m\) ports.

Edge access parallelization

In the parallelized Graphicionado pipeline, the Read Edges stage (P3) is likely to become a performance bottleneck because it occasionally requires random off-chip memory accesses. Even for algorithms that don’t require these accesses, this stage is still a bottleneck because it can only process one edge per cycle, whereas previous stages can process one vertex per cycle. Real-world graphs often have many more edges than vertices, necessitating fetching multiple edges per cycle for high throughput. To address this, Graphicionado duplicates the Read Edges unit and parallelizes edge accesses.

Two implementations of parallelizing edge accesses: active-vertex-based algorithms, and complete edge access algorithms. In the active-vertex-based approach, each active vertex id is assigned to a Read Edges unit based on input queue occupancy, with edges loaded from memory then arbitrated and passed onto the crossbar switch. For complete edge access algorithms, each source vertex id is broadcasted to all Read Edges units, which only access edges with assigned destination vertex ids. The output of each Read Edges unit is directly connected to the virtual output queue of the crossbar switch.

Destination vertex access parallelization

When the optional destination vertex property array is utilized (stage P4 in Fig. 1), it can hinder performance due to random vertex reads. To address this issue, the authors employ a parallelization approach akin to the one used for parallel edge readers mentioned earlier. The Read DST Property module is duplicated, and each destination vertex id is assigned to the least occupied module to retrieve the destination VProperty. Vertex properties fetched from memory are then managed to generate a single output per cycle through arbitration.

Scalable On-chip Memory Usage

Graphicionado employs on-chip memory for two main purposes: performing temporary destination property updates (P7-P9) and reading the edge ID table (P3). This enhances the throughput of pipeline stages (P3, P7, and P9), reduces off-chip memory bandwidth wastage, and minimizes pipeline stall time by decreasing the latency of temporary destination vertex property updates. However, the scratchpad memory size may be insufficient to store all necessary data in many cases. This section investigates strategies to maximize the utilization of the limited on-chip scratchpad memory.

Graph slicing

To store temporary destination vertex properties, Graphicionado requires memory equivalent to Number of Vertices \(\times\) Size of a Vertex Property bytes. For instance, with a 4-byte vertex property size and a 32MB on-chip scratchpad, Graphicionado can support graphs with up to 8 million vertices. However, to process larger graphs while still benefiting from on-chip memory, Graphicionado slices the graph into multiple segments and processes each segment individually.

Here’s how the slicing technique works: First, the input graph’s vertices are divided into \(N\) partitions based on their vertex IDs. Next, two slices are created based on which partition the destination vertices of the edges belong to. Each slice is processed sequentially, with the Processing phase executed for one slice followed by the Apply phase, and then repeating the process for the next slice. This slicing approach ensures that write-write conflicts are avoided, and no edges are processed twice. However, slicing may slightly increase the total read bandwidth usage as some source vertex properties may be read multiple times.

Extended graph slicing for symmetric graphs

Graph slicing, while separate from most Graphicionado optimizations, requires additional pipeline extensions when used alongside symmetric graph optimization. With symmetric graph optimization, the scratchpad memory must accommodate both the source and destination vertex property arrays, rendering the standard slicing ineffective as it doesn’t reduce on-chip storage needs. To address this, an extended slicing scheme is employed. In this scheme, for a symmetric graph, Graphicionado generates a directed graph, retaining only edges originating from a larger vertex ID to a smaller one. Three slices are then constructed based on this directed graph: Slice1 includes edges between vertices in partition P1, Slice2 includes edges from P2 to P1, and Slice3 includes edges between vertices in partition P2. Unlike the original scheme, this extended approach considers both source and destination IDs for slicing, generating \(N(N + 1)/2\) slices with \(N\) partitions. To operate with this extended slicing, Graphicionado requires control extensions. Firstly, it ensures that all edges associated with vertices to be updated have undergone the Processing phase before Apply begins. Apply occurs selectively in sub-iterations where a vertex partition is processed for the last time. Additionally, since each sub-iteration doesn’t fully process all edges, temporary vertex property data in scratchpad memory must be stored to memory and reloaded between Processing phases. The control flow is pre-determined based on the number of vertex partitions, with necessary write-backs of scratchpad memory data determined in advance. Thus, at runtime, Graphicionado simply follows the predetermined control flow.

Coarsening edge ID table

The on-chip scratchpad in Graphicionado serves another purpose: storing the EdgeIDTable, which maps vertices to their starting edge IDs. When the EdgeIDTable is too large for on-chip storage, a coarsened version is used. This coarsened table stores an edge ID for every \(N\) vertices (e.g., \(N = 2\)), reducing storage requirements. To locate edges for a given vertex ID, the Read Edges unit begins at index \(\lfloor vid/N \rfloor\) in the coarsened EdgeIDTable, where \(vid\) is the vertex ID and \(N\) is the coarsening factor.

However, using a coarsened EdgeIDTable introduces extra edge accesses, necessitating a careful balance between on-chip storage size and these additional accesses. It’s worth noting that the slicing technique employed reduces the average degree per vertex, thus lessening the overhead of coarsening the EdgeIDTable.

Results

Evaluation Methodology

Overall Design

The Graphicionado pipeline stages were implemented using Chisel and converted to Verilog. Synthesis was performed using a sub-28nm design library, targeting an operating voltage of 0.7V and a clock cycle of 1ns. The slowest module has a critical path of 0.94ns, ensuring a comfortable operation at 1GHz.

Evaluation Tools

A custom cycle-accurate simulator was developed to model the microarchitecture behavior of each hardware module and integrate a detailed scratchpad memory model. DRAMSim2 was utilized to simulate off-chip memory accesses, while the on-chip scratchpad memory was modeled using the CACTI 6.5 eDRAM model.

Software Framework Evaluation

Graphicionado’s performance and energy efficiency were compared with GraphMat, a highly optimized software graph processing framework. GraphMat was chosen due to its superior performance and efficiency compared to other frameworks. Power consumption was measured using National Instrument’s power measurement data acquisition PCI board.

Graph Datasets

A variety of real-world and synthetic graph datasets were used for evaluation, including FR, FB, Wiki, LJ, TW, NF, RMAT, and SB. Synthetic graphs were generated using the Graph500 RMAT data generator and a bipartite graph generator. Different graphs were used to evaluate various algorithms, such as PageRank, BFS, SSSP, and CF. Random integer weights were assigned for unweighted real-world graphs used in the SSSP evaluation.

Graphicionado Results

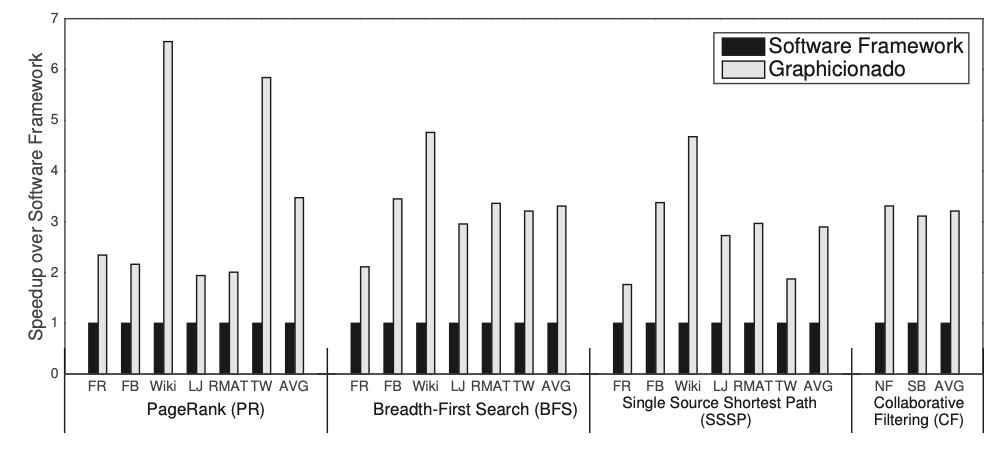

Overall Performance

Figure 4 displays Graphicionado’s speedup compared to GraphMat, a software graph processing framework, normalized for comparison. Despite Graphicionado’s 64MB on-chip storage, not large enough for all workloads, techniques like graph slicing and edge table coarsening are employed for larger graphs. Graphicionado achieves a performance boost of 1.7\(\times\) to 6.5\(\times\) over GraphMat running on a 16-core 32-thread Xeon server. Its main performance advantage lies in efficiently utilizing on-chip scratchpad memory. Unlike the software framework, which often faces limitations due to inefficient memory bandwidth usage, Graphicionado optimizes memory usage by leveraging scratchpad memory, resulting in enhanced performance.

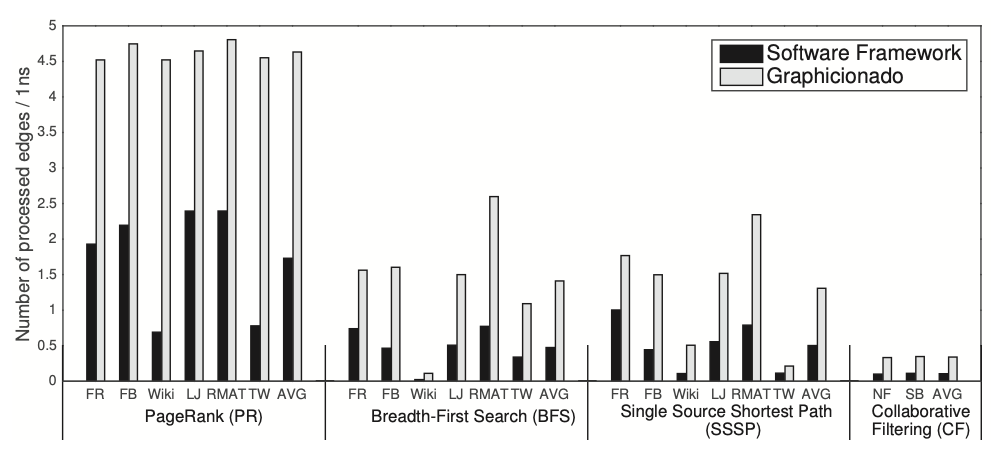

Throughput

In Figure 5, the comparison between Graphicionado and the software graph processing framework is illustrated in terms of throughput. The y-axis represents the average number of edges processed per nanosecond. Notably, PageRank achieves a stable and high throughput of about 4–4.5 edges per nanosecond on Graphicionado due to the absence of random memory accesses in its pipeline. While it theoretically could reach a peak throughput of processing 8 edges per cycle with proper prefetching, it is constrained by off-chip memory bandwidth. Conversely, active-vertex based algorithms like BFS and SSSP exhibit lower throughput due to random memory accesses compared to PageRank. Wiki, characterized by its narrow and deep graph structure, displays low throughput on both Graphicionado and GraphMat, attributed to numerous iterations updating few vertices each time. Additionally, CF demonstrates notably low edge processing throughput owing to its large vertex property size (128 bytes), which strains off-chip memory bandwidth alongside edge accesses.

Communication Efficiency

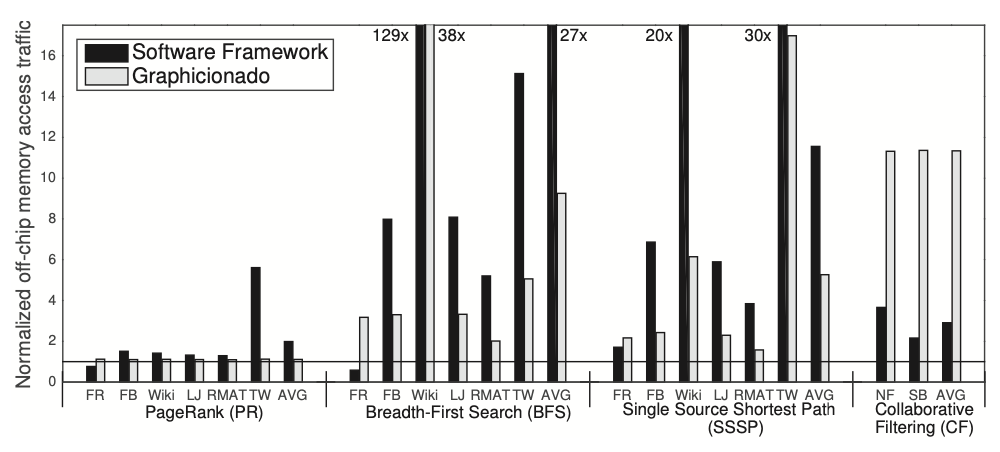

In Figure 6, the efficiency of off-chip memory accesses for Graphicionado and GraphMat is depicted. Efficiency is measured as the ratio of off-chip memory traffic normalized to the optimal communication scenario, where all data is stored on-die for each iteration but not across iterations. For PageRank, both Graphicionado and GraphMat demonstrate lower off-chip communication due to the absence of random accesses. However, for BFS and SSSP, Graphicionado accesses 2\(\times\)-3\(\times\) more off-chip data than the optimal case in most graphs, with GraphMat exhibiting even higher bandwidth usage. This discrepancy is attributed to off-chip bandwidth waste, more prevalent in software frameworks. In the case of CF, Graphicionado’s off-chip bandwidth consumption is roughly 10 times higher than optimal due to loading destination vertex properties at 128 bytes per edge. Although the software framework requires less off-chip communication for CF, its performance is constrained by other factors like memory latency and compute throughput.

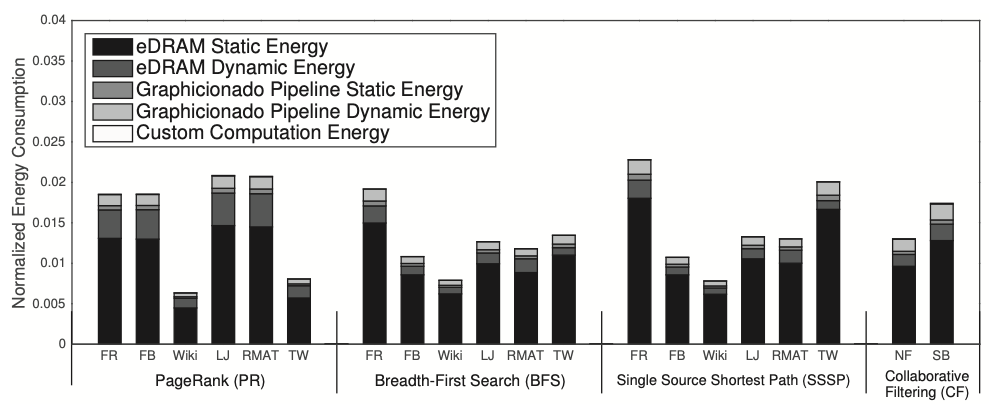

Power/Energy

In Figure 7, the energy consumption of Graphicionado is compared to GraphMat on a Haswell Xeon server, with Graphicionado’s energy normalized to that of GraphMat. Energy per access and eDRAM leakage power are derived from the 32nm eDRAM model in CACTI 6.5, with conservative estimates provided. Each hardware unit in the Graphicionado pipeline is assumed to operate at peak activity. The diagram illustrates that Graphicionado’s energy consumption is approximately 1-2% of the processor’s energy consumption. Notably, power consumption differs significantly, with the Xeon chip consuming around 20 times more power (about 150W) compared to Graphicionado (approximately 7W). This, combined with a 2-5\(\times\) difference in runtime, results in a total energy difference of 50\(\times\)-100\(\times\). In Figure 6, nearly 90% of the energy is attributed to eDRAM usage, while the hardware modules themselves, primarily consisting of specialized routing and control units, contribute minimally to overall energy consumption. It’s important to note that Graphicionado’s energy consumption does not account for the DRAM controller energy, as it could potentially be located off-die, unlike the integrated memory controller in the Xeon processor.

Effects of Graphicionado optimizations

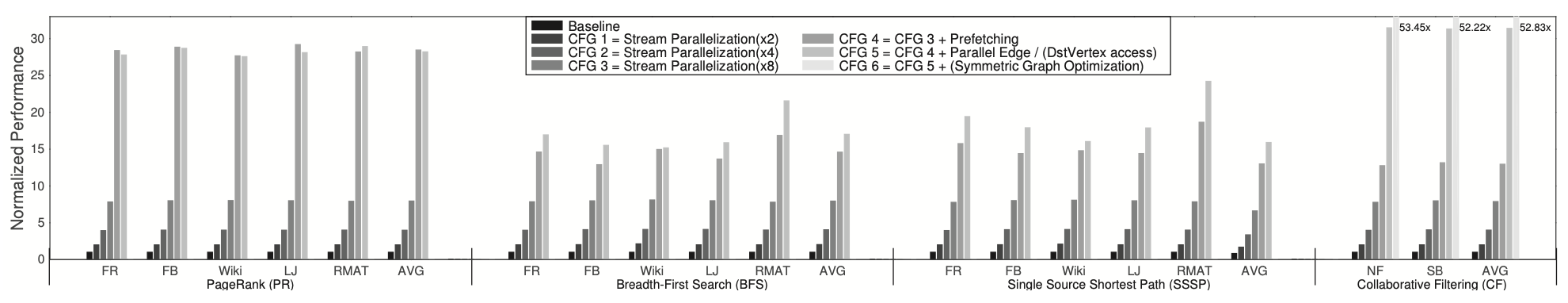

Parallelization/Optimization

This section investigates the impact of parallelization and optimization on the Graphicionado pipeline. In Figure 8, the leftmost bar represents the baseline scenario with a single stream, denoted as “Baseline,” which utilizes on-chip scratchpad memory and edge access pattern optimization. Subsequently, the number of streams is doubled from CFG 1 to CFG 3. CFG 4 demonstrates the effects of data prefetching, while CFG 5 illustrates the impact of parallelizing edge and destination vertex property access. CFG 6, specific to CF, showcases the effects of applying symmetric graph optimization. The results show that parallelizing Graphicionado streams leads to nearly linear speedups. Introducing data prefetching yields an additional 2\(\times\) speedup. Furthermore, parallelizing edge access for active-vertex based algorithms results in a 1.2\(\times\) speedup, and combining this with destination vertex property parallelization provides another 2\(\times\) speedup for CF. However, PageRank does not experience any extra speedup from CFG 4 to CFG 5, as it is already limited by memory bandwidth. Lastly, symmetric graph optimization boosts CF performance by an additional 1.7\(\times\) by reducing the number of edges needing processing through halving.

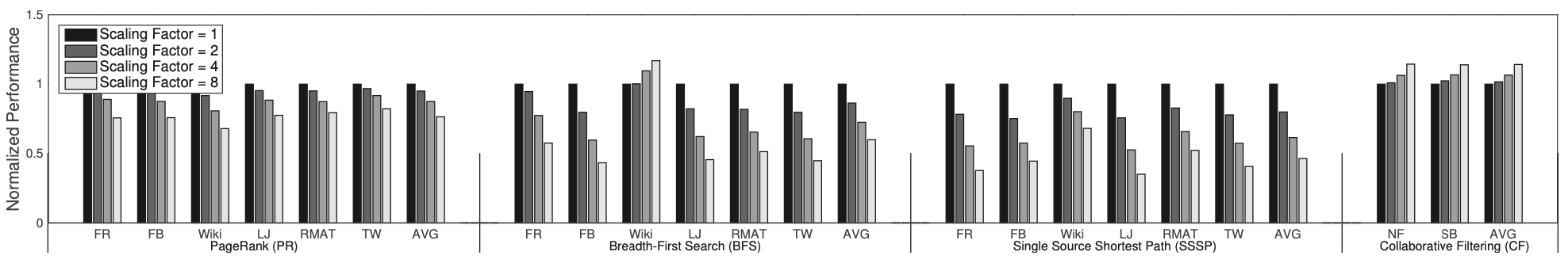

Graph Slicing and Edge Table Coarsening

Figure 9 illustrates the impact of graph slicing and edge table coarsening techniques. The leftmost bar represents the scenario where the scratchpad memory size is sufficient to accommodate all necessary data, labeled as Scaling Factor\( = 1\). Subsequent bars depict cases where the scratchpad memory size is reduced to \(1/N\) of the total required size, where \(N\) is the scaling factor. For each scaling factor \(N\), the input graph is sliced into \(N\) slices (or \(N(N+1)/2\) for the extended slicing scheme), and the EdgeIDTable is coarsened by a factor of \(N\). Generally, reducing the scratchpad memory size to one-eighth of the required data size results in approximately a 30% performance degradation in PageRank, a 35% degradation in BFS, and a 50% degradation in SSSP. Despite the performance degradation, Graphicionado still outperforms the software graph processing framework running on a server-grade multiprocessor while consuming less than 2% of the energy. Notably, for BFS-Wiki and CF, slicing leads to a graph distribution where some slices have either no edges to process or no vertices to update, resulting in the skipping of either the Processing or the Apply phase for multiple iterations, ultimately improving performance compared to the no-slicing case.

In summary, as shown in Figure 9, Graphicionado demonstrates the ability to handle very large graphs with acceptable performance degradation. Moreover, considering the ongoing trend of increasing on-chip storage for processors, such as Intel’s i7-5775C and IBM’s Power8, we anticipate that most intermediate data from real-world graphs will fit into larger on-chip eDRAM with a reasonable scaling factor.

Critical Review

Pros

- Graphicionado achieves significant speedup (1.76-6.54\(\times\)) compared to leading software frameworks, demonstrating its effectiveness in processing graph analytics tasks.

- Despite its high performance, Graphicionado consumes less than 2% of the energy of a 16-core Haswell Xeon server, highlighting its energy efficiency.

- The paper discusses the careful design of Graphicionado’s pipeline, addressing inefficiencies in existing processors and maximizing memory-level parallelism with minimal complexity.

Cons

- The paper primarily compares Graphicionado against a single software framework (GraphMat) and a specific hardware architecture (16-core Haswell Xeon server). Including comparisons with a wider range of software frameworks and hardware architectures could provide a more comprehensive evaluation.

- The paper does not discuss the cost implications of implementing and deploying Graphicionado, which could be a significant factor for potential users or adopters.

Takeaways

In this paper, the authors introduce Graphicionado, a specialized accelerator tailored for graph analytics processing. Based on a widely-used vertex programming model found in popular software frameworks, Graphicionado enables users to perform graph analytics tasks with high performance and energy efficiency, while maintaining the flexibility and simplicity of software-based approaches. The design of Graphicionado’s pipeline addresses inefficiencies present in general-purpose processors by optimizing on-chip scratchpad memory usage, balancing pipeline designs for increased throughput, and maximizing memory-level parallelism with minimal complexity. The experiments conducted by the authors demonstrate that Graphicionado achieves significant speedup (1.76-6.54\(\times\)) compared to leading software frameworks, while consuming less than 2% of the energy of a 16-core Haswell Xeon server. These findings suggest that Graphicionado offers a promising solution to meet the growing demand for efficient graph processing platforms.

References

- T. J. Ham, L. Wu, N. Sundaram, N. Satish, and M. Martonosi, “Graphicionado: A high-performance and energy-efficient accelerator for graph analytics,” in 2016 49th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), 2016, pp. 1–13.