Research Paper Review: GenAx - A Genome Sequencing Accelerator

This paper introduces GenAx, a specialized accelerator designed to expedite the read alignment process, which is a time-intensive task in genome sequencing. GenAx comprises two main components: a seeding accelerator and a seed-extension accelerator. The seed-extension accelerator utilizes an innovative automata design specifically crafted for hardware acceleration. Unlike traditional Levenshtein automata, it is independent of input string length and scales quadratically with edit distance rather than string length. It supports essential features like affine gap scoring and traceback commonly used in sequencing. GenAx achieves a notable throughput of 4,058K reads per second for Illumina 101 base pair reads. Compared to the standard BWA-MEM sequence aligner running on a powerful server processor, GenAx achieves a remarkable 31.7\(\times\) increase in speed while consuming 12\(\times\) less power and occupying 5.6\(\times\) less area.

Paper Summary

Genomics holds immense promise for transforming healthcare through precision medicine. With the decreasing costs of sequencing, genome testing is poised to become more accessible to a broader population. However, the efficient handling and analysis of the vast amount of raw genome data pose significant challenges. Existing sequencing software often demands extensive CPU resources, with read alignment being a particularly time-consuming process. Commercial software predominantly relies on the Broad Institute’s BWA-MEM software for this task, considering its output as the industry standard. The primary objective of the paper is to develop an accelerator that maintains alignment fidelity with existing software standards while eliminating the need for heuristic approaches.

The process of read alignment entails determining the precise location of a read within the genome, while accommodating variants and sequencing errors. This process unfolds in two primary stages: seeding and seed-extension. Seeding involves pinpointing perfect matches in the reference genome for small sections of the read, followed by seed-extension, which refines these matches through an approximate string matching algorithm rooted in Levenshtein distance.

The paper introduces GenAx, an ASIC custom hardware accelerator catering to both seeding and seed-extension. Addressing the irregular access issue inherent in seeding, the team tackles it by segmenting the genome into smaller cache-able indexes. Each segment undergoes individual seeding. Despite potentially yielding more seeds for extension than the baseline approach, GenAx achieves high-throughput seed extension through its accelerator for approximate string matching.

The paper introduces Silla, a novel automata designed to facilitate efficient and scalable hardware acceleration of approximate string matching. Unlike traditional methods such as Levenshtein Automata (LA), Silla adopts a state-based approach, representing the number and types of edits rather than tracking matched positions. This design choice allows for the collapse of the state machine from a 3D to a more efficient 2D structure.

Silla is characterized by its string independence, enabling it to compute edit distances for any pair of strings. With a state count of only \((K + 1)^2\), where \(K\) denotes the edit distance, Silla demonstrates excellent scalability. Its regular and composable structure ensures that states communicate solely with local neighbors in a 2D plane.

Leveraging Silla’s unique properties, the researchers developed SillaX, an efficient hardware accelerator requiring minimal gates per state and operating at a high frequency. SillaX supports various functionalities crucial for seed-extension in genome sequencing, including affine gap penalty computation and traceback.

In practical implementation, SillaX demonstrates impressive performance metrics, with high frequency, low power consumption, and compact area requirements. The accelerator achieves significant speedup compared to optimized banded Smith-Waterman on a server processor.

Additionally, the paper introduces GenAx, a genome sequencing read alignment accelerator that integrates SillaX with a seeding accelerator. This combined approach addresses irregular memory accesses by segmenting the genome and generating cache-able indexes for efficient seeding within each segment. GenAx offers notable improvements in speed, power consumption, and alignment throughput compared to standard BWA-MEM aligners.

In summary, the contributions outlined in the paper encompass the development of Silla, an innovative automata for computing edit distances, the design of SillaX for approximate string matching acceleration, and the creation of GenAx for read alignment in genome sequencing, showcasing the integration of SillaX with a seeding accelerator to enhance efficiency and throughput.

Seed Extension: Background and Motivation

The sequencing process involves identifying potential matching positions (hits) in the reference genome for a given read through seeding, followed by seed extension where the read is matched with the reference strings at these hit positions using an affine gap function. The Smith-Waterman algorithm, typically employed for approximate string matching in seed extension, faces scalability issues with increasing string length due to its \(O(N^2)\) time and space complexity. While FPGA-based hardware accelerators have been proposed for Smith-Waterman, they struggle with long reads and space overhead in traceback. Levenshtein Automata offers an alternative for approximate string matching, but its time complexity and impracticality for hardware acceleration limit its use in sequencing software. The Universal Levenshtein Automata (ULA) addresses some of LA’s limitations but lacks efficient hardware realizations, hindering its application in sequencing software.

Silla Algorithm

The paper presents String Independent Local Levenshtein Automata (Silla), a non-deterministic finite-state automaton aimed at efficiently accelerating approximate string matching in hardware. Unlike Smith-Waterman approaches, Silla’s space complexity scales quadratically with edit distance rather than string length, making it suitable for matching long strings with a limited edit distance. Notably, Silla is string-independent, enabling it to process any pair of strings, and employs local communication between adjacent states for scalability without performance degradation. Its regular and composable structure allows smaller instances to be combined into larger ones, crucial for efficient hardware acceleration. Silla targets the computation of the minimum Levenshtein distance between two strings, provided it falls below a specified threshold \(K\).

Silla, initially designed for handling insertions and deletions (indels), employs state-based representation where states indicate the number and type of edits made, rather than tracking matches explicitly like Levenshtein automata. It begins computation from a start state and utilizes retro comparisons to adjust offsets based on indel types, progressing through accepting states representing potential alignments within the specified edit distance. To accommodate substitutions, Silla extends into 3D by introducing additional states, with each layer representing a 2D indel Silla. However, to address hardware implementation challenges, a collapsed 3D Silla is devised by consolidating states, resulting in a simplified version conducive to efficient hardware implementation. Silla also employs merging confluence paths, where multiple solutions are explored simultaneously, ensuring safety and efficiency in state merging due to consistent string partitioning and path-independent suffix computation.

Silla Accelerator for Genome Sequencing

This section introduces SillaX, a hardware accelerator designed for genomics applications. Employing a systolic array architecture, SillaX efficiently computes and distributes retro comparisons to all states. In addition to handling edit distance, it supports advanced scoring schemes such as the affine gap penalty, which is vital in genomics. Moreover, it incorporates traceback functionalities to trace the sequence of edits leading to the final alignment solution, an essential feature for seed-extension in genome sequence alignment.

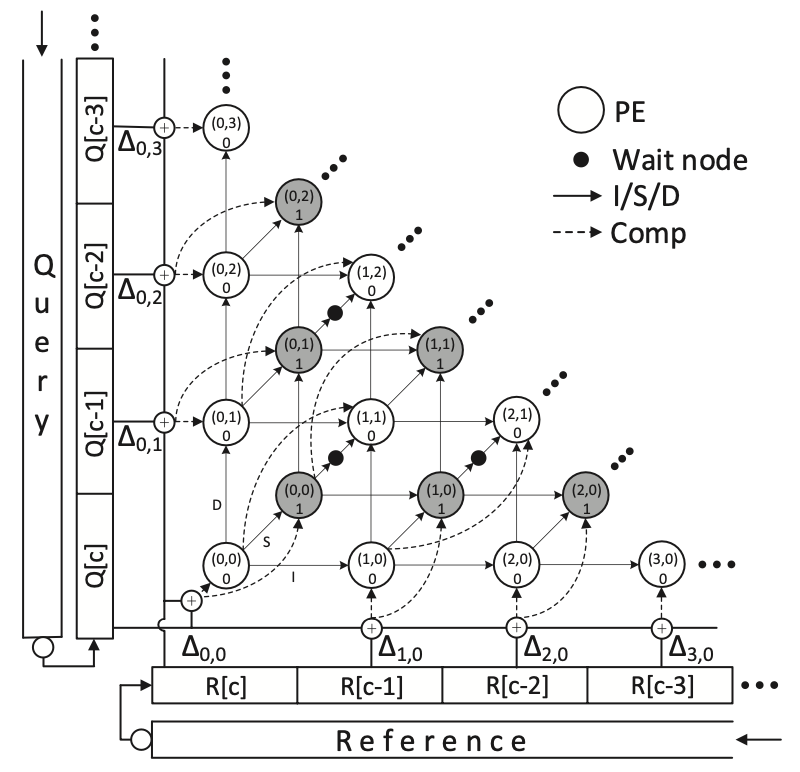

SillaX Edit Machine: SillaX implements each regular state in Silla as a small processing element (PE), ensuring that every state communicates solely with its neighbors via a locally communicating regular network (Figure 1). Retro comparisons for states are efficiently calculated and distributed across cycles, with many comparisons being reused across two clock cycles, reducing the need for redundant computations. By leveraging shift registers and comparators, SillaX achieves scalable design and efficient retro comparison distribution, significantly reducing complexity compared to software implementations. SillaX requires \(O(K^2)\) states and operates in about \(N\) cycles, where \(K\) is the edit distance and \(N\) is the string length, making it highly efficient for hardware acceleration, particularly in comparison to software implementations with \(O(N^2)\) time complexity. Additionally, SillaX’s implementation in 28nm technology allows for a clock speed of 6 GHz and requires only 13 gates per PE, showcasing its efficiency compared to alternative hardware accelerators.

Scoring Machine: The edit distance serves as a basic measure of alignment between two strings, while more complex scoring schemes, like those used in genome sequencing, incorporate empirical evidence from analyzing numerous genomes. In scoring alignments, paths with open gaps have an advantage over closed paths due to the scoring scheme’s penalties for indels and substitutions. To address this, a delayed merging technique is introduced, where scores are latched and compared in subsequent cycles to ensure accurate selection of the best path. Additionally, a clipping heuristic is applied to select the best score seen during seed-extension rather than relying solely on final states, considering potential sequencing errors at the ends of reads. SillaX scoring machine supports this clipping heuristic by back-propagating best scores from each state, resulting in efficient space (\(O(K^2)\)) and time (\(O(N)\)) performance despite additional overheads.

Traceback Machine: Read alignment involves determining the sequence of edits and their positions in a string, known as traceback. Traditional hardware accelerators often rely on software for this step, leading to bottlenecks, or require hardware space proportional to the read length. To address this, a traceback mechanism is introduced, utilizing a pointer trail and compressing the trace representation by counting matches discovered at each state. The traceback machine operates in five phases: accepting best scores, propagating back the best score and final state identifier, signaling the winner, flagging the winning path, and collecting the trace. To handle potential breaks in the pointer trail, a mechanism is implemented to inform upstream neighbors and re-run the machine if necessary. Despite the additional phases, the traceback machine’s overheads are significantly lower than previous hardware accelerators, offering efficient space utilization.

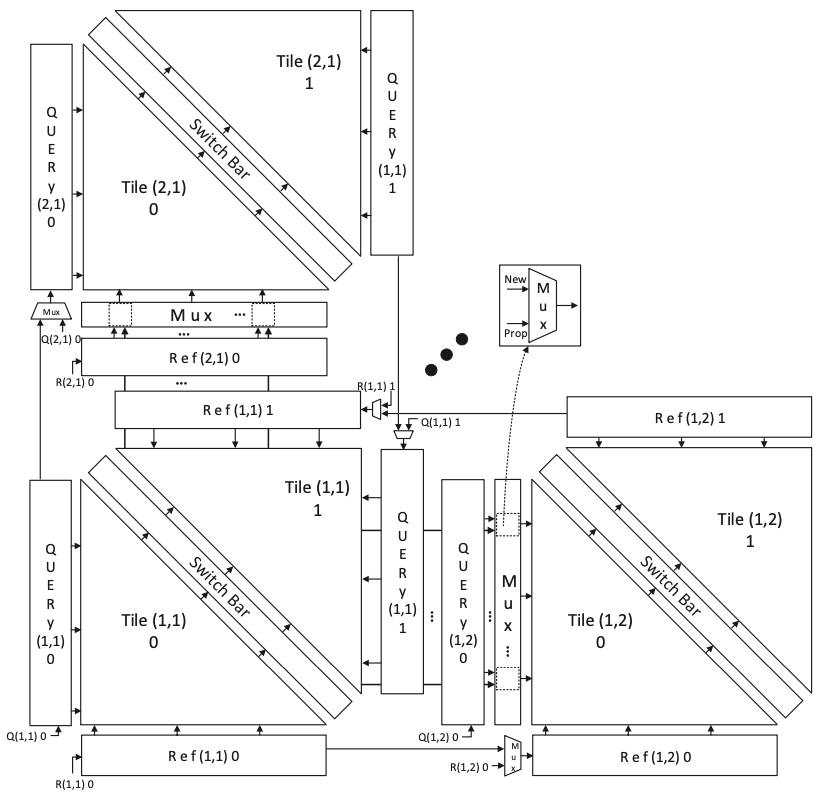

Composable SillaX: Maintaining flexibility in hardware acceleration is crucial for addressing a wide range of applications, particularly concerning different string and edit lengths. While the SillaX accelerator already accommodates arbitrary string lengths, the maximum edit distance is fixed by the hardware’s PE grid size. To overcome this limitation, a solution is proposed involving composable sub-grids, where multiple smaller SillaX engines can be combined into larger ones or reconfigured into multiple smaller engines with varying edit distances. This approach offers versatility, allowing for optimal adaptation to the targeted application space by seamlessly switching between different configurations. The concept is illustrated with an example involving six small SillaX accelerator tiles that can operate independently or be combined to create larger engines with different edit distances (Figure 2). This reconfiguration method incurs minimal overhead and significantly broadens the application space of SillaX, allowing for edit distances ranging from \(K\) to \(pK\), where \(p = \sqrt{T}\) for \(T\) Tiles.

Seeding Accelerator

Seeding is crucial in read alignment for identifying potential matches in a reference genome. BWA-MEM defines seeds as substrings of reads with super-maximal exact matches (SMEMs) in the reference genome, wherein a maximal exact match (MEM) is an unextendable exact match. An SMEM is a MEM not wholly contained within another MEM in the read. Traditional hardware accelerators for seeding often suffer from poor memory locality. This work proposes an improved seeding algorithm that efficiently finds all hits akin to BWA-MEM but with enhanced memory locality. The algorithm involves computing right maximal exact matches (RMEMs) using an index table and a position table. To optimize performance, the accelerator segments the genome and constructs index and position tables for each segment, enabling low-latency access in on-chip SRAM. Notably, the accelerator employs optimizations for intersecting hit sets, including on-chip CAM and binary search techniques. Additionally, it efficiently seeds reads with exact matches in the reference genome, significantly enhancing performance for a common scenario where the majority of reads have exact matches.

GenAx Genomics Accelerator

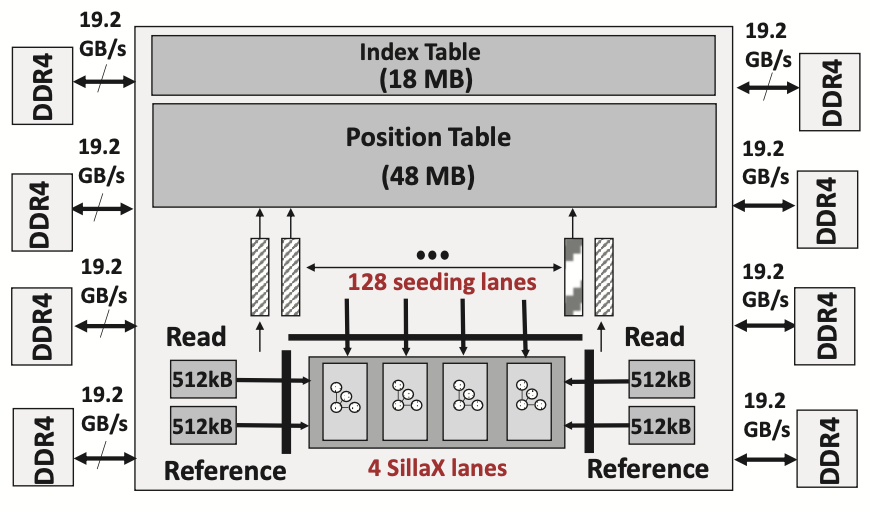

GenAx combines the seeding and SillaX seed-extension accelerators for fast sequence alignment of human genomes. Its architecture (Figure 3) includes 128 seeding lanes. These lanes fetch k-mer positions from a 48 MB index table and reference hits from an 18 MB position table. Each lane processes one read at a time, using a CAM and a small control FSM to manage SMEM intersections and k-mer lookups. The resulting hits are buffered for seed-extension by the four SillaX lanes, each with sufficient throughput to handle hits from all 128 seeding lanes. A SillaX lane retrieves the reference string from a 4 \(\times\) 512 KB reference cache to extend a seed at a specific hit position. A 16 KB buffer is used to buffer processed reads. The reference genome, segmented into 512 segments of 6 million base-pairs each, fits into the reference cache. These segments are processed sequentially for all reads, with the necessary data streamed in from memory via 8 DDR4 channels, leveraging spatially co-located memory accesses for efficiency.

Results

Evaluation Methodology

The researchers utilized the GRCh38 assembly from the UCSC genome browser and real human genome reads from the Illumina platinum genomes dataset for evaluation. They compared the performance of GenAx with BWA-MEM on an Intel Xeon E5-2697 CPU and CUSHAW2-GPU on Nvidia’s TITAN Xp. SillaX’s alignment throughput was evaluated independently against Smith-Waterman algorithm implementations using both CPU and GPU baselines. The SillaX accelerator was synthesized using Synopsys Design Compiler in a commercial 28nm process, obtaining area, power, and latency metrics for different clock frequency targets. The reference genome was segmented into 512 segments, with index and position tables constructed for each, requiring 48 MB and 18 MB of on-chip SRAM, respectively. Ramulator was used to compute memory cycles for loading these tables and performing SillaX compute in each segment.

SillaX Evaluation

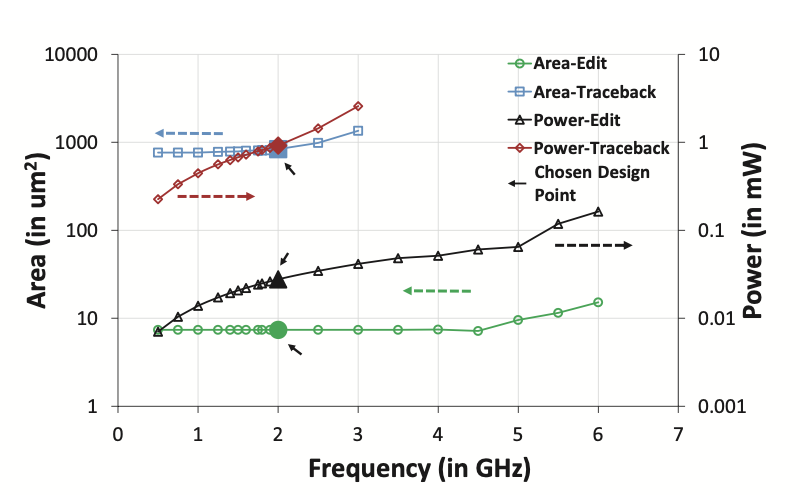

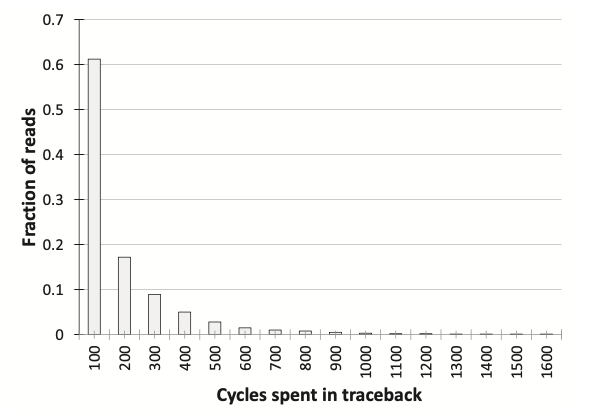

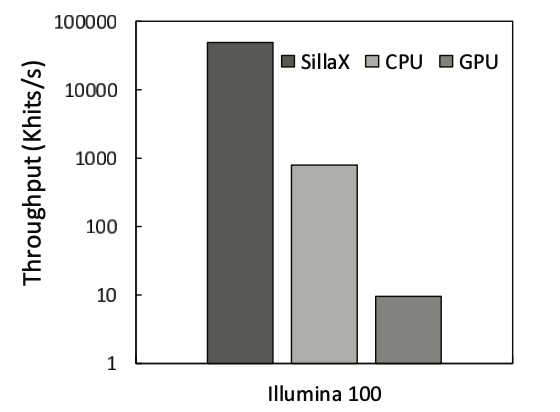

The power, area, and latency metrics of the SillaX edit machine and traceback machine are presented (Figure 4), showcasing optimal design points. The SillaX edit machine, at 2 GHz, occupies 0.012 \(mm^2\) area, consumes 0.047W power, and has a latency of 0.17 \(ns\), while the traceback machine occupies 1.41 \(mm^2\) area, consumes 1.54W power, and has a latency of 0.33 \(ns\). Validation of the SillaX traceback machine using non-exact matching reads against BWA-MEM alignments shows close agreement with negligible variance (0.0023%) and identical alignment scores. Evaluation of broken pointer trail events indicates that only 7.59% of reads required re-execution, with most events resolved within the first 101 cycles (Figure 5). Additionally, SillaX demonstrates significant throughput improvements over CPU and GPU-based solutions for aligning 100bp Illumina short reads (Figure 6), achieving a \(\sim\)62.9\(\times\) throughput improvement over SeqAn and a \(\sim 5287 \times\) speedup over SW#, while consuming 6.6W of power and occupying 5.64 \(mm^2\) area. These benefits are attributed to its linear time processing of input symbols and efficient traceback support, reducing synchronization overheads compared to GPU-based solutions.

GenAx Evaluation

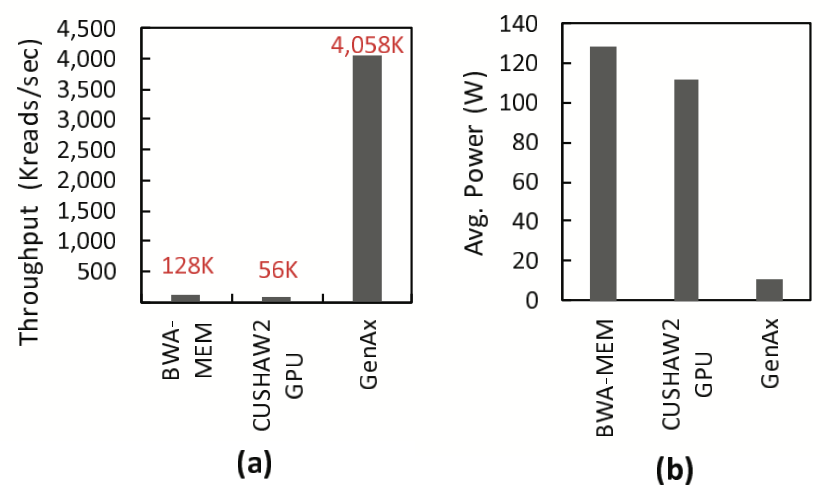

In Figure 7(a), GenAx’s throughput is compared with BWA-MEM (CPU) and CUSHAW2-GPU, showing a 31.7\(\times\) speedup over BWA-MEM and a 72.4\(\times\) speedup over CUSHAW2-GPU. This improvement is attributed to efficient SillaX accelerators for seed-extension with in-place traceback, segmenting and on-chip storage of index and position tables for low-latency access, minimal time spent on read loading, and optimization for perfect matches.

Figure 7(b) compares the average power consumption of GenAx with BWA-MEM and CUSHAW2-GPU, demonstrating a 12\(\times\) reduction compared to BWA-MEM on CPU by sharing indexing lanes with SillaX accelerators. The area breakdown highlights a significant portion dedicated to seeding acceleration using on-chip index and position tables, with each seeding lane featuring a 512-entry CAM and SillaX lanes consisting of counters and logic gates.

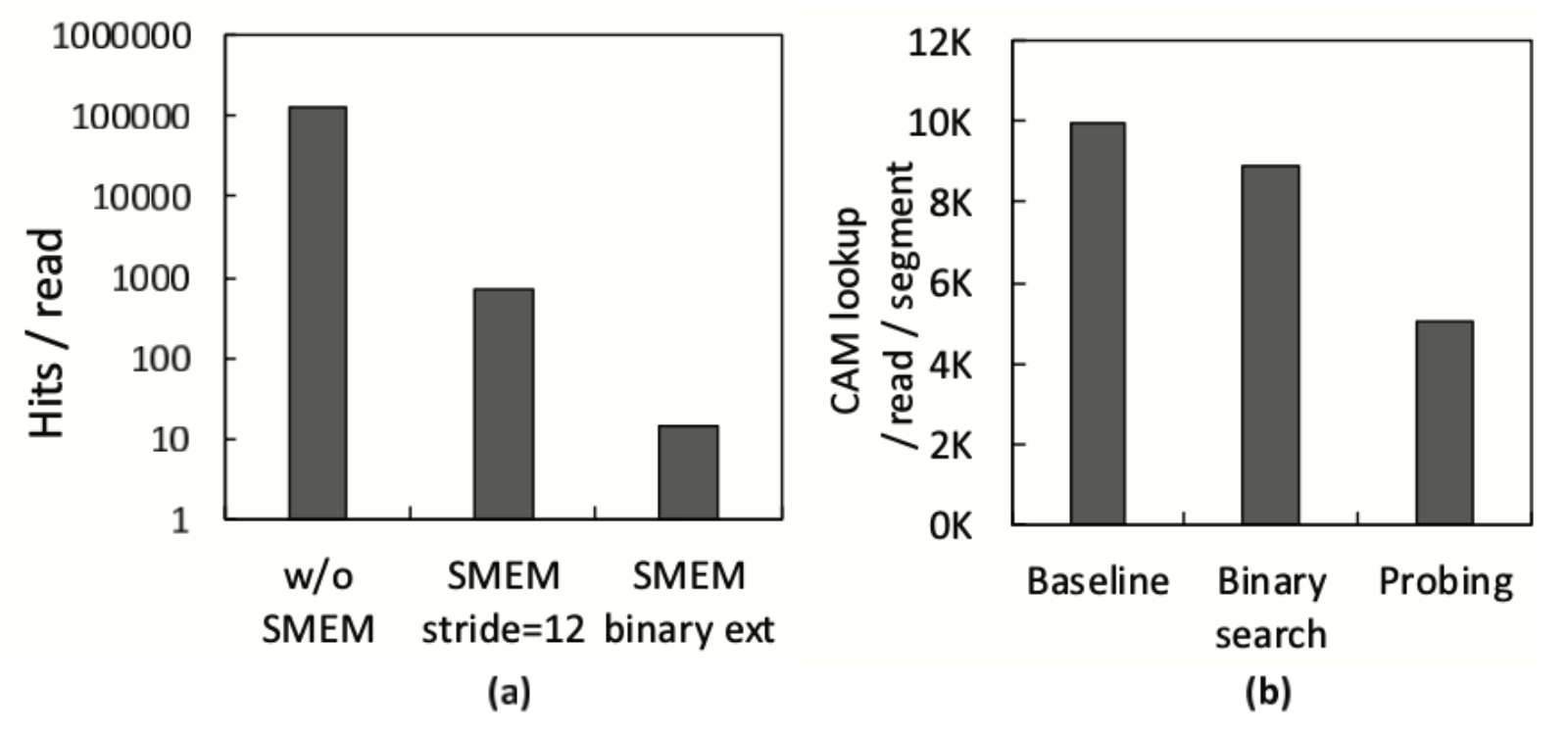

The seeding performance breakdown in Figure 8(a) illustrates the average number of hits generated by hash tables, with lower values indicating better processing. Optimizations such as SMEM and binary extension effectively reduce insignificant hits, substantially decreasing the workload downstream for the SillaX machine.

Figure 8(b) demonstrates the reduction of CAM lookups resulting from position table lookup optimizations. The binary lookup of the position table leads to logarithmic search time, reducing the number of CAM lookups proportionally. Effective probing helps find a better starting point with k-mers having fewer hit positions, further decreasing overall CAM lookups.

Comparison with Banded Smith-Waterman

SillaX offers significant advantages over traditional banded Smith-Waterman implementations and introduces novel features. It occupies substantially less area, with each PE being 30 times smaller compared to banded Smith-Waterman PEs. This efficiency holds even with a high edit distance (\(K=32\)) for Illumina short reads alignment. Moreover, SillaX enables efficient in-place traceback within PEs, eliminating the need for extra space typically required by hardware-based banded Smith-Waterman implementations. Unlike existing accelerators, SillaX achieves traceback in \(O(K^2)\) space or less without compromising time complexity.

SillaX’s foundation in automata theory grants it versatility and adaptability. It can be easily mapped to automata processors accommodating variable-width input symbols, enhancing implementation flexibility. Algorithmically, SillaX not only succeeds Levenshtein automata but also extends its utility to various problems such as Longest Common Sequence and automatic spell correction, expanding its applicability beyond bioinformatics.

Critical Review

Pros

- GenAx achieves significant speedup compared to existing software-based and GPU-based aligners, demonstrating its effectiveness in high-throughput sequence alignment.

- The evaluation of GenAx against BWA-MEM shows negligible variance in alignment results, indicating high accuracy.

- By sharing indexing lanes with SillaX accelerators, GenAx reduces power consumption significantly compared to BWA-MEM executed on CPU.

Cons

- Although segmenting the index and position tables improves memory access efficiency, the paper does not address potential bottlenecks in memory bandwidth, especially for large datasets.

- The paper primarily compares GenAx against BWA-MEM and CUSHAW2-GPU, but additional comparisons with other state-of-the-art aligners or hardware accelerators could provide a more comprehensive evaluation.

Takeaways

This paper contributes to this advancement by introducing an accelerator that enhances the efficiency of sequence aligners. GenAx achieves an impressive throughput of 4,058K reads/s for Illumina 101 bp reads. Compared to the standard BWA-MEM sequence aligner running on a dual-socket 14-core Xeon E5 server processor, GenAx achieves a remarkable 31.7\(\times\) speedup while reducing power consumption by 12\(\times\) and area by 5.6\(\times\).

References

- D. Fujiki, A. Subramaniyan, T. Zhang, Y. Zeng, R. Das, D. Blaauw, and S. Narayanasamy, “Genax: A genome sequencing accelerator,” in 2018 ACM/IEEE 45th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), 2018, pp. 69–82.