Research Paper Review: EIE - Efficient Inference Engine on Compressed Deep Neural Network

This paper introduces an Energy Efficient Inference Engine (EIE), aiming to process inference tasks on compressed network models efficiently. EIE achieves energy savings of 120\(\times\) by switching from DRAM to SRAM, with an additional 10\(\times\) savings by exploiting sparsity. Weight sharing and skipping zero activations from ReLU contribute 8\(\times\) and 3\(\times\) savings, respectively. Across nine DNN benchmarks, EIE outperforms CPU and GPU implementations by 189\(\times\) and 13\(\times\), respectively, without compression. Operating directly on compressed networks, EIE reaches a processing power of 102 GOPS/s, equivalent to 3 TOPS/s on uncompressed networks, and achieves a processing speed of 1.88\(\times\)10\textsuperscript{4} frames/sec for FC layers of AlexNet, with only 600mW power dissipation. Compared to CPU and GPU alternatives, EIE is 24,000\(\times\) and 3,400\(\times\) more energy-efficient. Additionally, compared to DaDianNao, EIE demonstrates superior throughput, energy efficiency, and area efficiency, with improvements of 2.9\(\times\), 19\(\times\), and 3\(\times\), respectively.

Paper Summary

Neural networks are widely used in various applications like computer vision and natural language processing, often containing millions or even billions of parameters. However, the energy consumption of large models is a significant concern, especially for embedded mobile devices, as they rely heavily on external DRAM access, which is energy-intensive.

Previous efforts to accelerate DNNs have primarily focused on dense, uncompressed models, limiting their usefulness to smaller models or scenarios where high energy costs are tolerable. Model compression techniques such as pruning and weight sharing enable fitting modern networks like AlexNet and VGG-16 into on-chip SRAM, but processing these compressed models poses challenges due to sparse matrices and relative indexing complexities.

To efficiently handle compressed DNN models, this paper introduces EIE, an efficient inference engine specialized in sparse matrix-vector multiplication and weight sharing without loss of efficiency. EIE consists of scalable processing elements (PEs), each storing a partition of the network in SRAM and capable of exploiting dynamic input vector sparsity, static weight sparsity, relative indexing, weight sharing, and extremely narrow weights (4 bits).

In this design, each PE holds 131K weights of the compressed model, equivalent to 1.2M weights of the original dense model, and can perform 800 million weight calculations per second. With an area of 0.638mm\(^2\) and power dissipation of 9.16mW at 800MHz in 45nm CMOS technology, an EIE PE offers efficient processing. For example, the fully-connected layers of AlexNet fit into 64 PEs, consuming a total of 40.8mm\(^2\) and operating at 1.88 \(\times\) 10\(^4\) frames/sec with a power dissipation of 590mW.

Compared to CPU (Intel i7-5930k), GPU (GeForce TITAN X), and mobile GPU (Tegra K1), EIE achieves acceleration of 189\(\times\), 13\(\times\), and 307\(\times\), respectively, while providing significant energy savings of 24,000\(\times\), 3,400\(\times\), and 2,700\(\times\).

Motivation

Matrix-vector multiplication (M\(\times\)V) serves as a fundamental operation in various neural networks and deep learning tasks.

During M\(\times\)V, memory access often becomes the bottleneck, especially when dealing with matrices larger than the cache capacity. Without input matrix reuse, a memory access is required for each operation, posing a challenge on CPUs and GPUs. While batching is commonly used to mitigate this issue by combining multiple vectors into a matrix, it increases latency, which is undesirable for real-time applications.

Compressing the neural network presents a solution to alleviate memory access bottlenecks in large layers. However, the irregular pattern resulting from compression complicates effective acceleration on CPUs and GPUs.

Existing accelerators also struggle with compressed networks. They typically only exploit static weight sparsity and cannot handle dynamic activation sparsity. Additionally, previous DNN accelerators need to expand the network to a dense form before operation, limiting efficiency. Hence, there’s a need for a specialized engine capable of operating efficiently on compressed networks.

Hardware Implementation

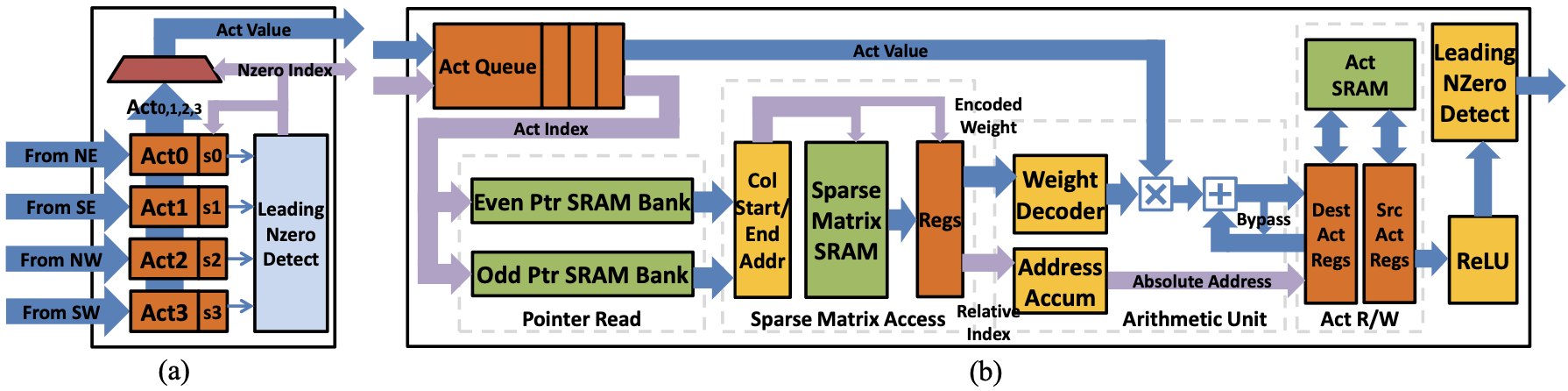

Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of EIE, comprising a Central Control Unit (CCU) governing an array of Processing Elements (PEs), each responsible for computing a segment of the compressed network. The CCU also manages the distribution of non-zero input activations received from a distributed leading non-zero detection network, broadcasting them to the PEs.

In EIE, most computations occur locally within the PEs, except for the collection and broadcast of non-zero input activations, which are non-critical in timing as most PEs take multiple cycles to process each activation.

The CCU broadcasts non-zero input elements and their corresponding indices to an activation queue in each PE. Broadcast is disabled if any PE’s queue is full, allowing each PE to process activations from its queue, thereby balancing the workload.

The index of the entry at the head of the activation queue is used to retrieve start and end pointers for the column’s data arrays. To optimize memory access, pointers are stored in dual SRAM banks, allowing simultaneous access to both pointers.

The sparse-matrix read unit utilizes pointers to read non-zero elements of the PE’s column slice from the sparse-matrix SRAM. Each entry contains an 8-bit element consisting of 4 bits each for the value (\( v \)) and index (\( x \)).

The arithmetic unit processes (\(v, x\)) entries from the sparse matrix read unit, performing the multiply-accumulate operation \(b_x = b_x + v \times a_j\). The input activation value (\(a_j\)) is multiplied by the value (\( v \)), expanded from 4-bit encoded form to a 16-bit fixed-point number. A bypass path is provided for consecutive cycles if the same accumulator is selected.

The Activation Read/Write Unit manages two activation register files for source and destination activation values during FC layer computation rounds. Activation vectors longer than 4K are handled in multiple batches, with local reduction performed in the register file.

Input activations are distributed hierarchically to each PE, utilizing leading non-zero detection logic for selecting the first non-zero result within each group of 4 PEs. The selected non-zero activation is broadcasted back to all PEs via the CCU.

The CCU operates in two modes: I/O and Computing. In I/O mode, PEs are idle while activations and weights can be accessed by a DMA. In Computing mode, the CCU collects non-zero values from the LNZD quadtree and broadcasts them to PEs repeatedly until the input length is exceeded, facilitating execution of different layers by configuring input length and pointer array start address.

Evaluation Methodology

The researchers developed a custom cycle-accurate C++ simulator to emulate the accelerator, aiming to replicate the Register Transfer Level (RTL) behavior of synchronous circuits. Each hardware module is represented as an object implementing two abstract methods: propagate and update, simulating combination logic and flip-flop behavior. This simulator aids in exploring design space and serves as a verification tool for RTL.

For assessing area, power, and critical path delay, the RTL of EIE was implemented in Verilog. The RTL was verified against the cycle-accurate simulator. Subsequently, EIE was synthesized using Synopsys Design Compiler (DC) under TSMC 45nm GP standard VT library with worst-case PVT corner. The placement and routing of the PE were conducted using Synopsys IC Compiler (ICC). SRAM area and energy figures were obtained using Cacti. Toggle rates from RTL simulation were annotated to the gate-level netlist, dumped to Switching Activity Interchange Format (SAIF), and power was estimated using Prime-Time PX.

EIE’s performance was compared with three off-the-shelf computing units: CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU.

- CPU: Intel Core i-7 5930k CPU, used in NVIDIA Digits Deep Learning Dev Box, was employed. MKL CBLAS GEMV implemented the original dense model, while MKL SPBLAS CSRMV was used for the compressed sparse model. CPU socket and DRAM power were measured using the

pcm-powerutility. - GPU: NVIDIA GeForce GTX Titan X GPU, a state-of-the-art GPU for deep learning, was chosen. cuBLAS GEMV implemented the original dense layer, while cuSPARSE CSRMV kernel optimized for sparse matrix-vector multiplication was used for the compressed sparse layer. Power was reported using the

nvidia-smiutility. - Mobile GPU: NVIDIA Tegra K1 with 192 CUDA cores was selected. cuBLAS GEMV was used for the original dense model, and cuSPARSE CSRMV for the compressed sparse model. Power consumption was measured using a power meter, with assumptions made for reporting AP+DRAM power.

Benchmarking involved comparing performance on two sets of models: uncompressed DNN models obtained from Caffe and NeuralTalk model zoos, and compressed DNN models produced as described in previous studies. The benchmark networks, totaling 9 layers from AlexNet, VGGNet, and NeuralTalk, were tested using the ImageNet dataset and Caffe deep learning framework as the golden model for verification.

Results

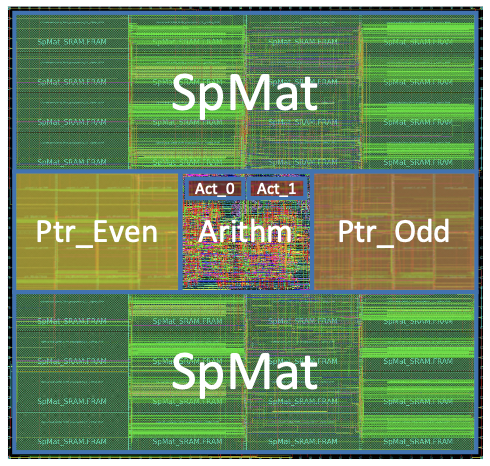

Figure 2 displays the layout of an EIE processing element following the place-and-route process.

To reduce the critical path delay to 1.15ns, four pipeline stages were introduced for updating one activation. These stages include codebook lookup and address accumulation (in parallel), output activation read and input activation multiply (in parallel), shift and add, and output activation write. Activation read and write access local registers, with activation bypassing used to prevent pipeline hazards. At 800MHz, 64 PEs achieve a performance of 102 GOP/s. Considering 10\(\times \) weight sparsity and 3\(\times \) activation sparsity, this requires a dense DNN accelerator to operate at 3TOP/s to match application throughput.

Each EIE PE has a total SRAM capacity (Spmat+Ptr+Act) of 162KB. The activation SRAM is 2KB, storing activations, while the Spmat SRAM is 128KB, holding compressed weights and indices. Weights and indices are grouped to 8 bits and addressed together, with each weight and index occupying 4 bits. The Spmat access width is optimized at 64 bits. The Ptr SRAM is 32KB, storing pointers in CSC format. In steady-state, both Spmat SRAM and Ptr SRAM are accessed every 8 cycles. SRAM dominates the area and power, accounting for 93% and 59% respectively. Each PE occupies 0.638mm\(^2\) and consumes 9.157mW. For every group of 4 PEs, a LNZD unit for nonzero detection is required. Thus, 21 LNZD units are needed for 64 PEs, with each LNZD unit consuming 0.023mW and occupying an area of 189\(\mu\)m\(^2\), less than 0.3% of a PE.

Performance

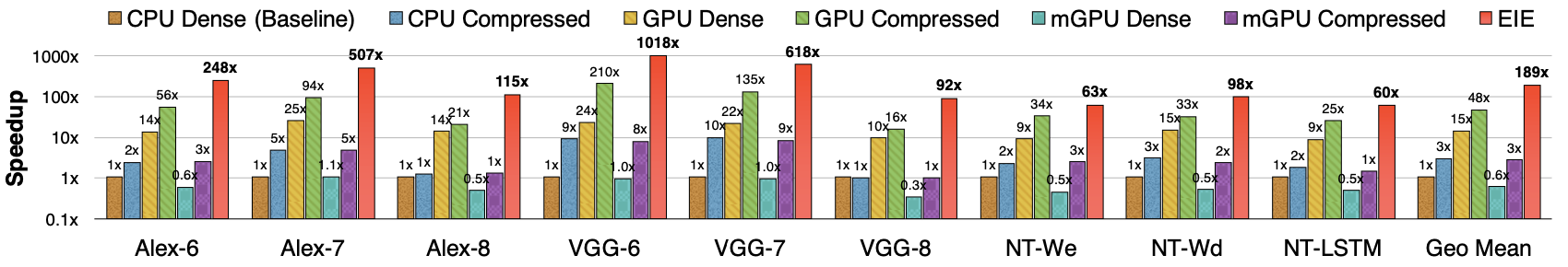

EIE’s performance is compared against CPU, desktop GPU, and mobile GPU across 9 benchmarks drawn from AlexNet, VGG-16, and Neural Talk, as depicted in Figure 3. Each benchmark presents 7 columns, comparing EIE’s computation time on compressed networks against CPU/GPU/TK1 on uncompressed/compressed networks. Time is normalized to CPU performance. EIE demonstrates significant superiority over general-purpose hardware, averaging 189\(\times\), 13\(\times\), and 307\(\times\) faster than CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU, respectively.

The theoretical computation time of EIE is derived by dividing workload GOPs by peak throughput. However, actual computation time is about 10% more due to load imbalance. In Figure 3, the comparison with CPU/GPU/TK1 is based on actual computation time.

EIE targets applications demanding real-time inference with minimal latency. Since batch assembly introduces notable latency, performance and energy efficiency are benchmarked with a batch size of 1 against CPU and GPU, as shown in Figure 3. EIE outperforms most platforms and matches the desktop GPU’s performance in the batching scenario.

EIE achieves its application throughput with significantly lower GOP/s compared to other approaches, leveraging sparsity to eliminate 97% of the GOP/s executed by dense methods. For instance, 3 TOP/s on an uncompressed network only requires 100 GOP/s on a compressed network. EIE’s throughput scales efficiently with over 256 PEs. Without EIE’s specialized logic, model compression applied solely on CPU/GPU yields only a 3\(\times\) speedup.

Energy

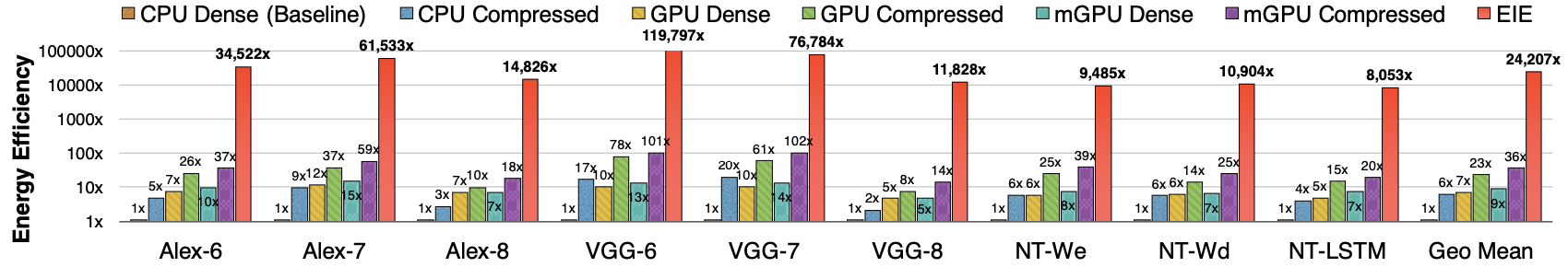

In Figure 4, the energy efficiency comparisons of M\(\times\)V across different benchmarks are presented. Each benchmark features 7 columns, comparing EIE’s energy efficiency on compressed networks against CPU/GPU/TK1 on uncompressed/compressed networks. Energy is calculated by multiplying computation time and total measured power.

On average, EIE consumes significantly less energy compared to CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU, with reductions of 24,000\(\times\), 3,400\(\times\), and 2,700\(\times\), respectively. This translates to a three-order-of-magnitude energy saving achieved through several factors. First, EIE leverages the energy savings per memory read by utilizing SRAM over DRAM: compressing network models enables advanced neural networks to fit in on-chip SRAM, reducing energy consumption by 120\(\times\) compared to fetching a dense uncompressed model from DRAM (as illustrated in Figure 4). Second, the compressed DNN model contains only 10% of the weights, each quantized to 4 bits, further reducing the number of required memory reads. Lastly, exploiting vector sparsity saves 65.14% redundant computation cycles. Multiplying these factors (120\(\times\)10\(\times\)8\(\times\)3) theoretically yields a 28,800\(\times\) energy saving. However, actual savings are about 10\(\times\) less due to index overhead and EIE’s implementation in 45nm technology, compared to the 28nm technology used by the Titan-X GPU and the Tegra K1 mobile GPU.

Design Space Exploration

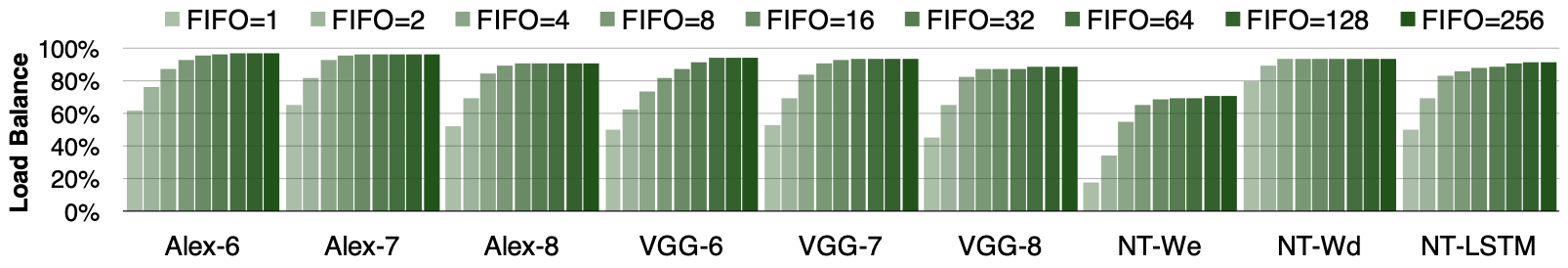

Queue Depth

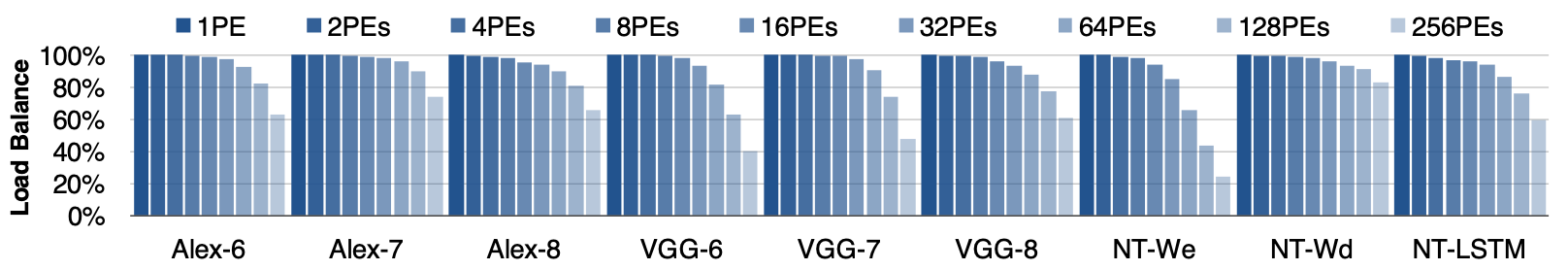

The activation FIFO queue is employed to address load imbalances among the PEs, effectively managing producer and consumer interactions. Through experimentation, as depicted in Figure 5, varying the FIFO queue depth from 1 to 256 in powers of 2 across 9 benchmarks with 64 PEs enabled measurement of the load balance efficiency. This efficiency, defined as 1 minus the ratio of bubble cycles (due to starvation) to total computation cycles, was assessed.

At a FIFO size of 1, approximately half of the total cycles were found to remain idle, indicating severe load imbalance. Increasing the FIFO depth mitigated load imbalance, yet the benefits plateaued beyond a depth of 8. Consequently, 8 was determined as the optimal queue depth.

It is noteworthy that the NT-We benchmark exhibited poorer load balance efficiency compared to others. This was attributed to its small size, comprising only 600 rows. With 64 PEs and considering 11% sparsity, each PE, on average, received a single entry, resulting in significant variation among PEs and exacerbating load imbalance. Such small matrices are more efficiently executed on 32 or fewer PEs.

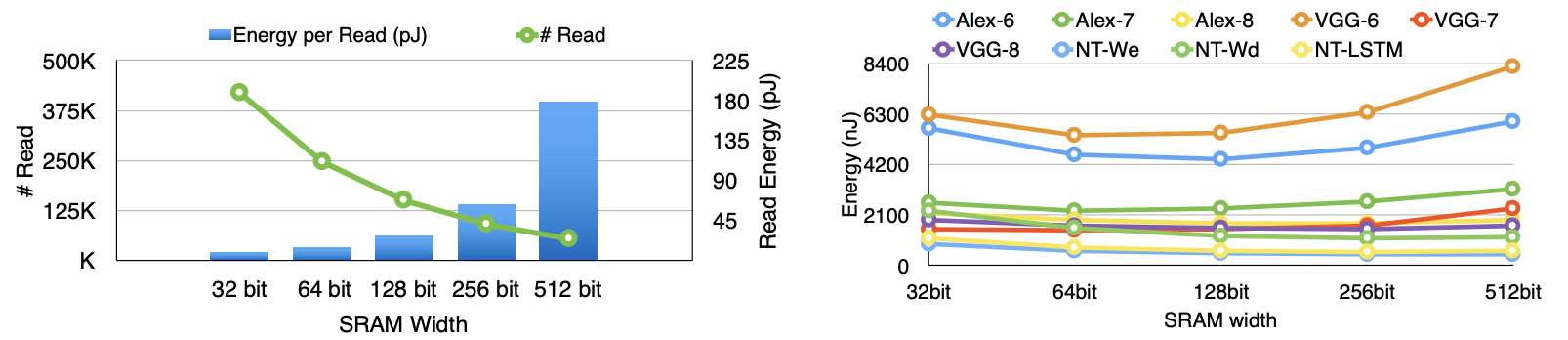

SRAM Width

An SRAM with a 64-bit interface was selected for storing the sparse matrix (Spmat) as it minimized the total energy consumption. Wider SRAM interfaces reduce the overall number of SRAM accesses but increase the energy cost per SRAM read. This trade-off is shown in Figure 6.

SRAM energy was modeled using Cacti under a 45nm process, while SRAM access times were measured using a cycle-accurate simulator on the AlexNet benchmark. The graph on the right illustrates the total energy, indicating that the minimum total access energy is achieved with a 64-bit SRAM width.

For larger SRAM widths, read data is wasted. Given a typical number of activation elements of 4K for the FC layer and assuming 64 PEs and 10% density, each column in a PE will average 6.4 elements. A 64-bit SRAM interface accommodates 8 elements. If additional elements are fetched and the subsequent column corresponds to a zero activation, those excess elements are squandered.

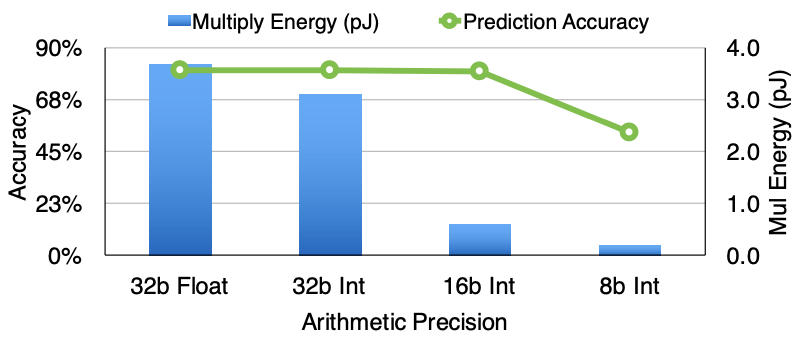

Arithmetic Precision

The team utilizes 16-bit fixed-point arithmetic, as depicted in Figure 7, which consumes 5\(\times\) less energy than 32-bit fixed-point and 6.2\(\times\) less energy than 32-bit floating-point calculations. Despite this efficiency, employing 16-bit fixed-point arithmetic results in a loss of prediction accuracy of less than 0.5%, achieving 79.8% accuracy compared to 80.3% using 32-bit floating-point arithmetic. However, reducing precision further to 8 bits notably decreases accuracy to 53%, rendering it unacceptable. Accuracy measurements were conducted on the ImageNet dataset with AlexNet, while energy consumption was derived from synthesized RTL under a 45nm process.

Research indicates that ‘Deep Compression’ techniques have negligible impact on accuracy. However, employing 16-bit arithmetic leads to only a 0.5% degradation in accuracy. To maintain absolute accuracy, transitioning to 32-bit arithmetic would have minimal effects on the power or area of EIE. Only the width of the 16-entry codebook, arithmetic units, and activation register files would need adjustment, while the index stored in SRAM would remain 4-bits. It’s important to note that the majority of power and area is attributed to SRAM, not arithmetic units. Additionally, the area reserved for filler cells is sufficient to double the area of the arithmetic units and activation registers.

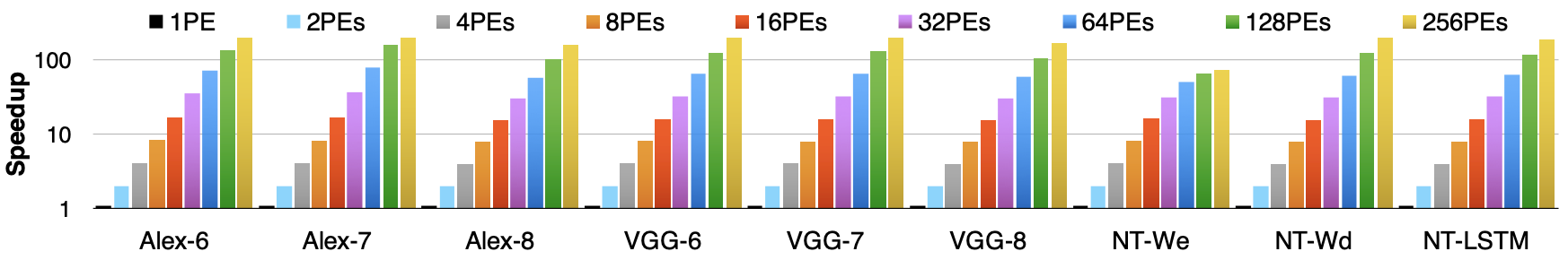

Scalability

In Figure 8, EIE demonstrates robust scalability across all benchmarks except for NT-We. NT-We, characterized by its small dimensions (4096 \(\times\) 600), experiences significant load imbalance when distributed among 64 or more PEs due to its column size of 600 and 10% sparsity.

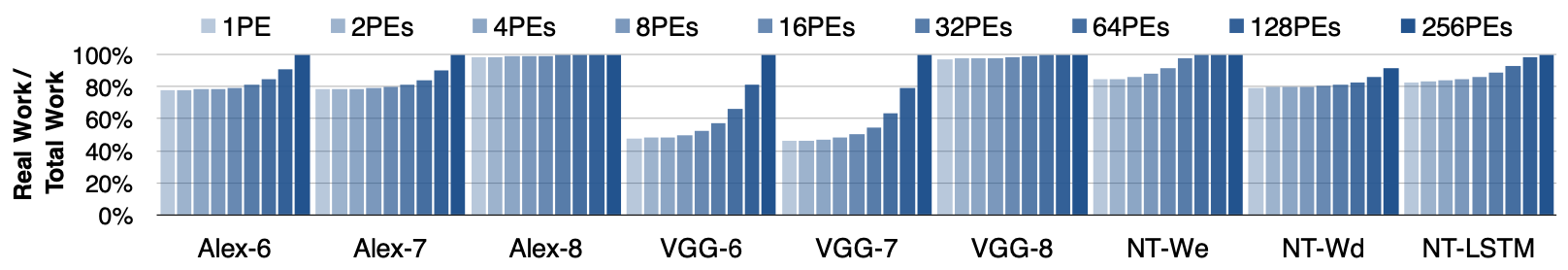

Figure 9 showcases the occurrence of padding zeros across different numbers of PEs. Padding zeros arise when the gap between two consecutive non-zero elements in the sparse matrix exceeds 16, the maximum value that 4 bits can encode. The utilization of more PEs reduces padding zeros by partitioning the matrix, narrowing the distance between non-zero elements, and increasing the likelihood of adequate 4-bit encoding.

Figure 10 illustrates load balance across varying numbers of PEs, measured with a FIFO depth of 8. While load balance deteriorates with more PEs, the overhead of padding zeros decreases. Consequently, efficiency remains relatively constant across most benchmarks. The scalability outcomes are depicted in Figure 8.

Comparison with Related Work

The performance, power, and area metrics for M \(\times\) V are compared across six neural network platforms, including Core-i7 (CPU), Titan X (GPU), Tegra K1 (mobile GPU), A-Eye (FPGA), DaDianNao (ASIC), and TrueNorth (ASIC), as detailed in Figure 11. Among these platforms, EIE stands out due to its high efficiency during matrix-vector multiplication, outperforming others significantly. While A-Eye specializes in CONV layers, its reliance on external DDR3 memory makes it susceptible to bandwidth issues. DaDianNao, with its uncompressed weights, faces limitations in handling large-scale networks without compression.

Model compression techniques, such as pruning and weight sharing, play a vital role in reducing memory energy. While GPUs achieve only a 3\(\times\) energy saving through compression, EIE boosts this to 3000\(\times\) by leveraging architecture tailored to exploit compression-induced irregularities.

Various DNN accelerators have been proposed, each with its strengths and limitations. DaDianNao, for instance, struggles with memory inefficiency and lacks the ability to exploit sparsity and weight sharing. In contrast, EIE efficiently stores compressed models in SRAM, leading to significantly lower power consumption.

Moreover, sparse matrix-vector multiplication (SPMV) accelerators have been developed to improve computational efficiency. However, existing SPMV accelerators for compressed deep networks fail to fully exploit dynamic activation sparsity and weight sharing, resulting in missed opportunities for energy savings.

Critical Review

Pros

- The paper introduces EIE, an energy-efficient engine optimized for compressed deep neural networks. By leveraging sparsity, weight sharing, and quantization techniques, EIE significantly reduces energy consumption compared to traditional GPU and CPU architectures.

- EIE’s architecture is scalable from one processing element (PE) to over 256 PEs, enabling linear improvements in energy efficiency and performance as the number of PEs increases.

- EIE outperforms CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU architectures on fully-connected layer benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness in real-world applications.

- The paper provides a thorough evaluation of EIE’s performance, power consumption, and area efficiency, backed by experiments and comparisons with existing architectures.

Cons

- EIE is tailored only for compressed deep neural networks, limiting its applicability to other types of neural network architectures.

Takeaways

Deep neural networks often encounter memory limitations, particularly in their fully-connected layers where matrix-vector multiplications occur. Real-time networks, unable to utilize batching for improved efficiency, face challenges in reducing the energy required to access their parameters.

To address this issue, this paper introduces EIE, an energy-efficient engine designed specifically for compressed deep neural networks. EIE capitalizes on sparsity in both activations and weights, along with weight sharing and quantization techniques. By pruning parameters by 10\(\times\) and reducing weights to 4 bits, EIE achieves significant energy savings. Additionally, fetching the smaller model from SRAM rather than DRAM yields a 120\(\times\) energy advantage. Furthermore, exploiting the sparsity in activation vectors reduces the number of fetched matrix columns, resulting in a 3\(\times\) energy savings.

With these optimizations, an EIE processing element (PE) can achieve 1.6 GOPS while occupying only 0.64mm2 and consuming just 9mW. Scaling from one PE to over 256 PEs enables nearly linear improvements in both energy efficiency and performance. On nine fully-connected layer benchmarks, EIE outperforms CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU by factors of 189\(\times\), 13\(\times\), and 307\(\times\), respectively. Moreover, it consumes 24,000\(\times\), 3,400\(\times\), and 2,700\(\times\) less energy than CPU, GPU, and mobile GPU, respectively.

References

- S. Han, X. Liu, H. Mao, J. Pu, A. Pedram, M. A. Horowitz, and W. J. Dally, “Eie: efficient inference engine on compressed deep neural network,” SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News, vol. 44, no. 3, p. 243–254, jun 2016. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/3007787.3001163