Research Paper Review: Overcoming the Limitations of Conventional Vector Processors

The paper showcases CODE, a scalable vector microarchitecture that enhances performance and tackles issues in vector processors such as the complexity and size of centralized vector register files, challenges in implementing precise exceptions, and the high cost of on-chip memory systems with high bandwidth and low access latency.

Paper Summary

Modern vector and data-parallel architectures excel in compute-intensive applications due to their superior performance and power efficiency compared to superscalar processors. Their appeal lies in the balance between the advantages of custom designs and the flexibility of general-purpose processors, coupled with simplicity and scalability using CMOS technology. Despite their strengths, obstacles hinder broader adoption, including challenges with centralized vector register files (VRF) complexity, implementing precise exceptions for vector instructions, and elevated costs of on-chip vector memory systems. To address these limitations, the paper introduces CODE, a microarchitecture design featuring a clustered vector register file (CLVRF) that efficiently separates operand staging and communication tasks among functional units. The simplicity of CLVRF, achieved by avoiding all-to-all communication, distinguishes it from conventional VRFs. CODE mitigates performance losses through extensive decoupling and a simple renaming table. In comparison with the VIRAM media processor, CODE outperforms by 26% in EEMBC benchmarks, scales efficiently to 8 functional units, and supports precise exceptions for vector instructions with minimal impact on performance. This design overcomes challenges associated with centralized VRFs, showcasing its potential for improved performance in multimedia processing.

Limits of Conventional Vector Processors

The paper initially outlines three limitations of conventional vector processors. Firstly, the complex nature of the centralized VRF, essential for high-bandwidth operand communication among Vector Functional Units (VFUs), poses challenges. With approximately \(3N\) access ports required for \(N\) VFUs, the associated complexities in area, power consumption, and access latency are proportional to \(O(N^2)\), \(O(log_4N)\), and \(O(N)\), respectively. However, techniques to reduce VRF complexity provide only a one-time reduction in constant factors and are unsuitable for designs with numerous VFUs. Secondly, achieving precise exceptions for virtual memory support and handling arithmetic faults proves difficult in vector processors, leading most to support imprecise exceptions or none at all. This challenge is compounded when aiming for precise virtual memory exceptions for vector loads and stores, necessitating a large Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB). Lastly, conventional vector processors demand an aggressive memory system, requiring high memory bandwidth to match high throughput in VFUs with multiple datapaths (multi-lane designs). Providing high memory bandwidth and low-latency memory can be achieved through the utilization of on-chip memory; however, this leads to an overall increase in the system cost.

The CODE Microarchitecture

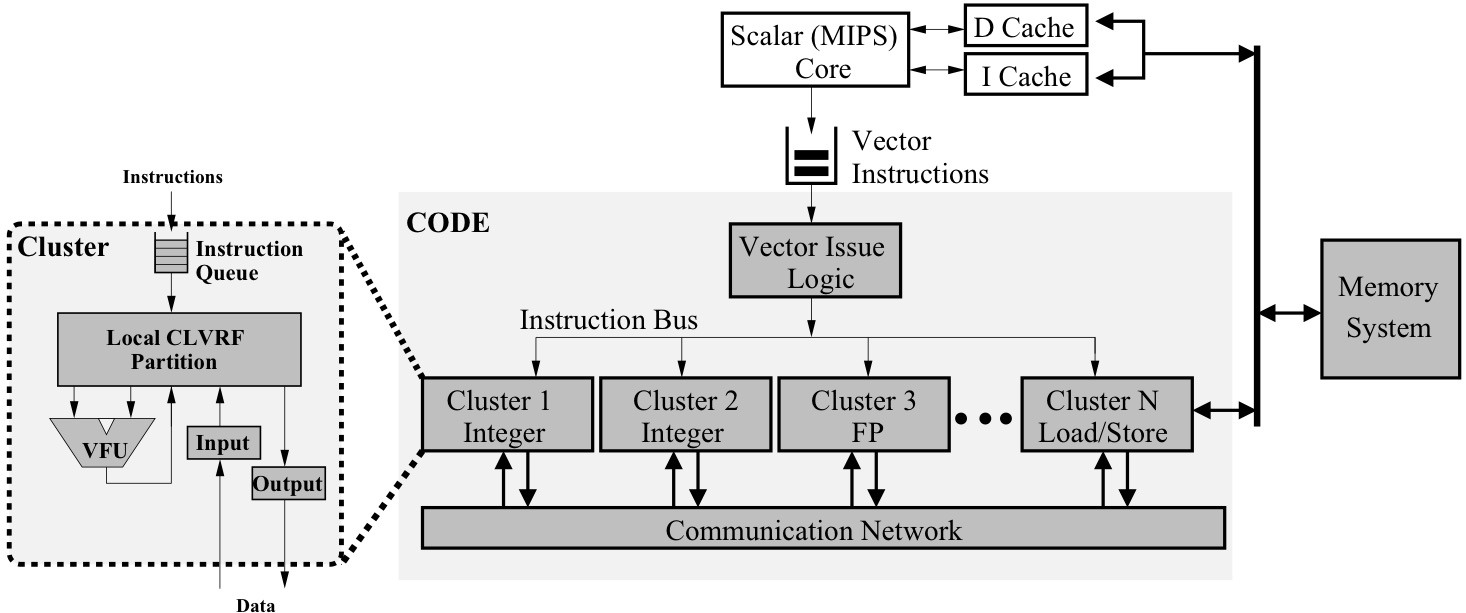

The paper then delves into detailing the CODE microarchitecture, as depicted in Figure 1, which illustrates the clustered organization of vector hardware. Each cluster in CODE comprises a single VFU (arithmetic or load-store) along with a small number of vector registers (e.g., 4 or 8). The clusters collectively store at least 32 vector registers, as specified in the ISA, with no predefined upper limit. Additionally, each cluster includes an instruction queue for decoupling purposes, as well as one input and one output interface facilitating vector register transfers between clusters. These interfaces lack storage, except for a single-cycle buffer for retiring.

Clustered Register File

CODE distributes vector registers across clusters, with each CLVRF partition providing operands to the local VFU and the communication interfaces. The CLVRF requires 5 access ports, including 2 read and 1 write for the VFU, 1 read for the output interface, and 1 write for the input interface. Importantly, the number of ports is independent of the overall cluster count, maintaining constant area, power consumption, access latency, and complexity for each CLVRF component. While the overall CLVRF and power consumption scale proportionally to \(N\), the area and power consumption per vector register in the CLVRF remain constant, thanks to each additional cluster contributing both a VFU and a few vector registers.

Communication Network

CODE employs a dedicated communication network to transfer vector registers between clusters, using tagged move-to and move-from instructions executed in the output and input interfaces, respectively. The hardware generates these move instructions, simplifying network control by using the same tag for corresponding moves. While full vector register transfers may span multiple cycles due to the network’s limited capacity, the communication is orchestrated efficiently. The paper discusses the need for a fair comparison between the CLVRF and centralized organization, emphasizing consideration of the communication network’s area, power, and complexity. Although the centralized VRF utilizes a single-cycle crossbar, if the CODE network is designed with similar functionality, the advantages of the CLVRF might be compromised. However, the argument suggests that a full crossbar network may not be essential due to the infrequent communication between certain VFUs, the common use of scalar values in vector instructions, and the limited lifespan of vector results. CODE’s separation of vector operand exchange from the VRF allows flexibility in designing the communication network, enabling low-cost implementations with simple networks or high-end implementations prioritizing low latency and high bandwidth. This flexibility introduces a trade-off between area, power, and network complexity for performance, while the cluster design remains unaffected.

Vector Issue Logic

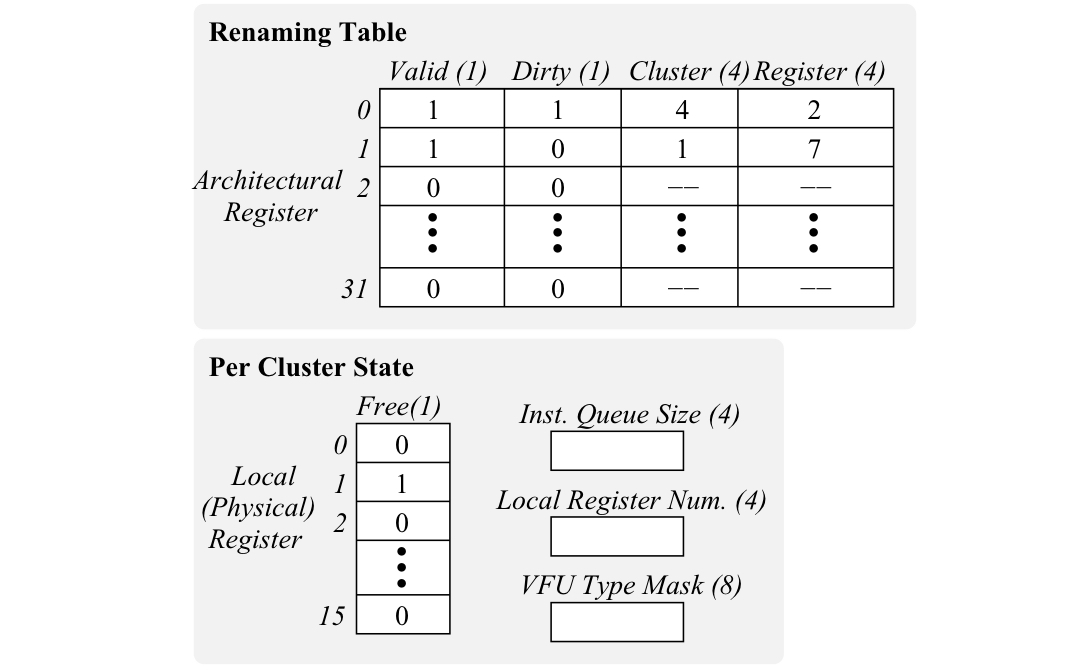

The vector issue logic plays a crucial role in selecting the appropriate cluster for executing instructions, especially in complex scenarios with only one cluster with the necessary VFU. To facilitate this, a renaming table (Figure 2) is employed to track the physical locations of the 32 architectural vector registers, eliminating WAW and WAR hazards between vector instructions. Additionally, as depicted in Figure 2, the per-cluster state includes a free-list for physical registers and control registers. Minimizing vector register transfers per instruction is essential to avoid stalls, necessitating high inter-cluster network bandwidth, which can be costly in terms of area and power. This highlights the importance of a robust cluster selection policy.

Discussion

CODE executes sequences of vector instructions in a decoupled manner, with in-order execution within each cluster, where each instruction typically spans several cycles. The use of instruction queues enables decoupling of execution across clusters, requiring synchronization only when queues reach capacity or data dependencies arise. A significant portion of inter-cluster transfer overhead is concealed by allowing input and output interfaces to prioritize move instructions, starting them ahead of older arithmetic instructions if there are no dependencies. This decoupled execution is crucial for CODE to evade the usual performance degradation linked to clustered register files. CODE simplifies the implementation of chaining, the vector equivalent of forwarding, in a scalable manner across numerous clusters, using only intra-cluster control logic. Additionally, CODE’s clustered organization is compatible with multi-lane implementations, where lanes and clusters provide orthogonal ways to add hardware resources. This allows CODE to be applied to a multi-lane vector processor by organizing resources within each lane into multiple clusters.

Support for Precise Exceptions

Despite the initially perceived challenges in implementing precise exceptions due to CODE’s decoupled nature, the renaming capabilities in the issue logic are leveraged to achieve an in-order commit of vector instructions without significant performance loss. This involves refraining from allowing a vector instruction to alter the value or physical location of an architectural register until it is confirmed that this and all preceding instructions will be complete without faults. To achieve an in-order commit, a history buffer is added to the issue logic, keeping track of changes to the renaming table and per-cluster state for each instruction. If an instruction completes without exception, old vector register mappings are released; if an exception occurs, the history buffer is scanned to restore mappings before flushing. Notably, the history buffer only stores mappings, not old vector register values, simplifying its design compared to those in superscalar processors. Supporting exceptions, however, increases pressure on vector registers, potentially causing stalls in the issue logic and performance loss due to the unavailability of most vector registers in a cluster storing old register values for pending instructions.

The history buffer in CODE facilitates the implementation of precise exceptions for vector instructions but does not simplify the TLB for vector loads and stores, necessitating an ISA-level change. The TLB requirement arises from the precise exception definition, which mandates that a faulting instruction cannot modify architecture state. To make progress, an indexed vector load must translate all its element addresses without exceptions. The proposed modification allows the faulting instruction to update architecture state up to the first element causing an exception, reducing the TLB’s necessity to a performance optimization rather than a functional requirement. Even with a single-entry TLB, an indexed load or store is guaranteed to advance by at least one element operation after each TLB miss exception. Processors optimized for specific access patterns may choose TLB sizes based on their application requirements. This approach, allowing partial completion of a vector instruction, resembles VLIW processors’ ability to resume from exceptions within a long instruction word. Implementing this technique involves a control register indicating the first element causing an exception, enabling the recognition that each vector or VLIW instruction defines multiple operations with independent exception behavior.

Evaluation

The paper evaluates CODE using a trace-driven, parameterized performance model that accounts for detailed timing events. The model incorporates an in-order scalar core with 8-KByte first-level caches, resembling the execution capabilities and area of a single-lane VIRAM processor. In the default configuration, it includes 2 integer and 1 load-store cluster, each equipped with 8 vector registers and an 8-entry instruction queue. An additional (4th) cluster introduces 16 vector registers, but includs no VFU. The memory system uses 8 banks of DRAM main memory and has 8 cycles latency.

The evaluation focuses on ten benchmarks from the EEMBC suite, chosen for their representation of multimedia device workloads with wireless or broadband communication capabilities. The benchmarks, being highly vectorizable, allow a concentration on the vector hardware design, the primary emphasis of the paper. Unlike scientific applications, EEMBC benchmarks cover both long and short vector operations, typical of multimedia applications. Traces for the CODE performance model were generated from the C benchmark code using the VIRAM vectorizing compiler and ISA simulator.

Results

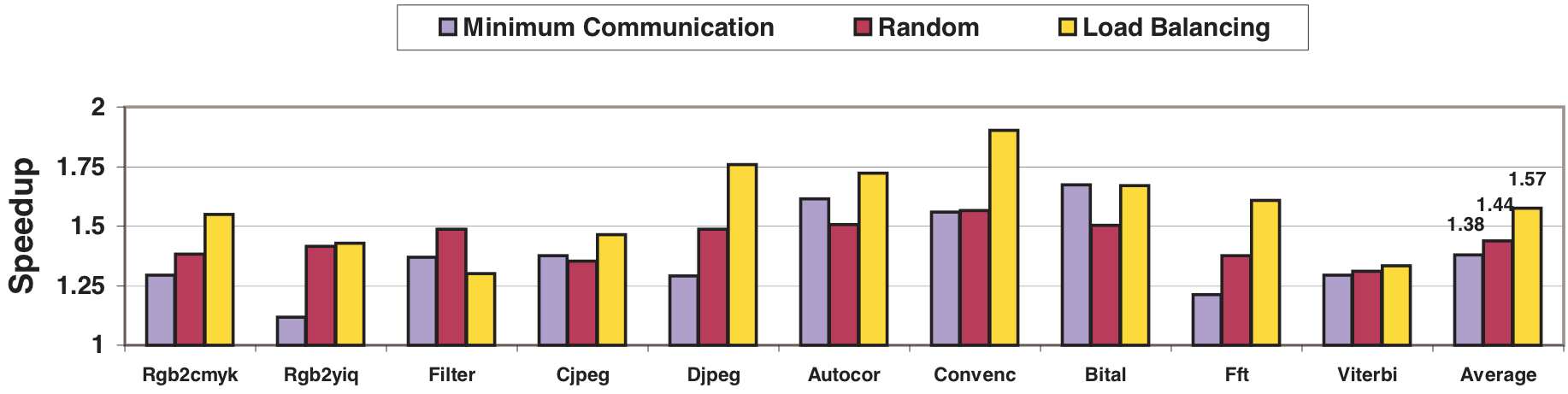

In Figure 3, the impact of cluster selection policy in a CODE configuration with 2 clusters for each vector instruction type is illustrated. This figure demonstrates the speedup over a configuration with a single cluster per type, where no selection is necessary. The selection of the cluster with the minimum register transfers reduces pressure on the communication network but introduces load imbalance. On average, this policy slightly underperforms compared to random selection. Load imbalance is addressed by considering the size of cluster instruction queues in the load balancing policy, leading to a 14% performance improvement over the minimum communication policy.

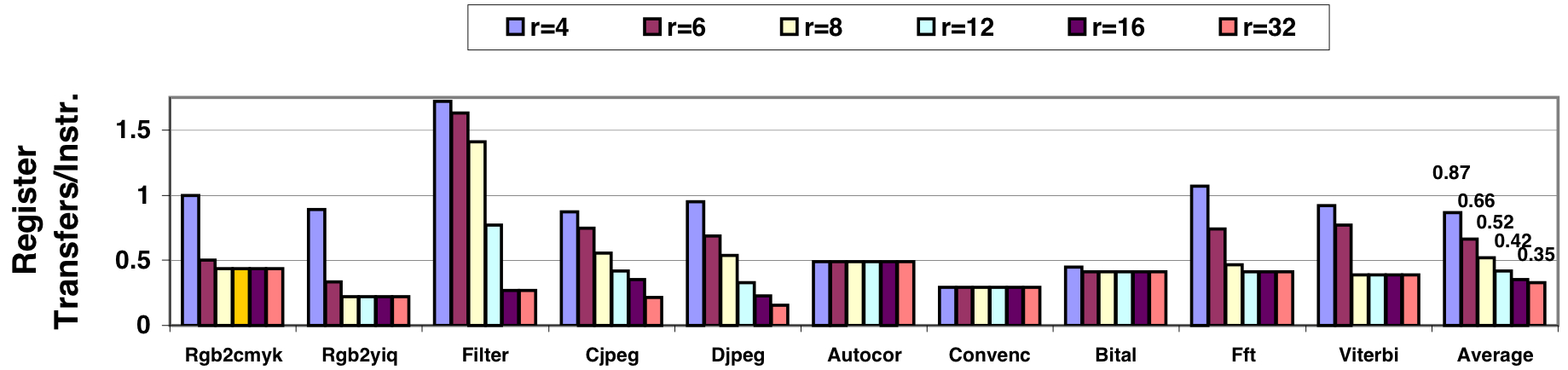

Another critical parameter is the number of vector registers per cluster. Insufficient local registers result in numerous intercluster transfers, potentially causing performance loss. Figure 4 displays the number of vector register transfers per instruction for the default configuration as a function of the number of vector registers per cluster. Eight registers per cluster are sufficient for holding operands and temporary results, resulting in less than one transfer per two vector instructions for all benchmarks except Filter.

The findings in Figure 4 indicate low actual requirements for inter-cluster communication. Experiments suggest that the ability to execute two register transfers in parallel at a rate of one 64-bit word per transfer per cycle is adequate for reaching the full performance potential with the default configuration. This bandwidth requirement is notably lower than that supported by the full crossbar integrated in a centralized VRF. Additionally, communication latency has no significant impact on CODE’s performance, thanks to decoupling providing sufficient tolerance for reasonable latency values.

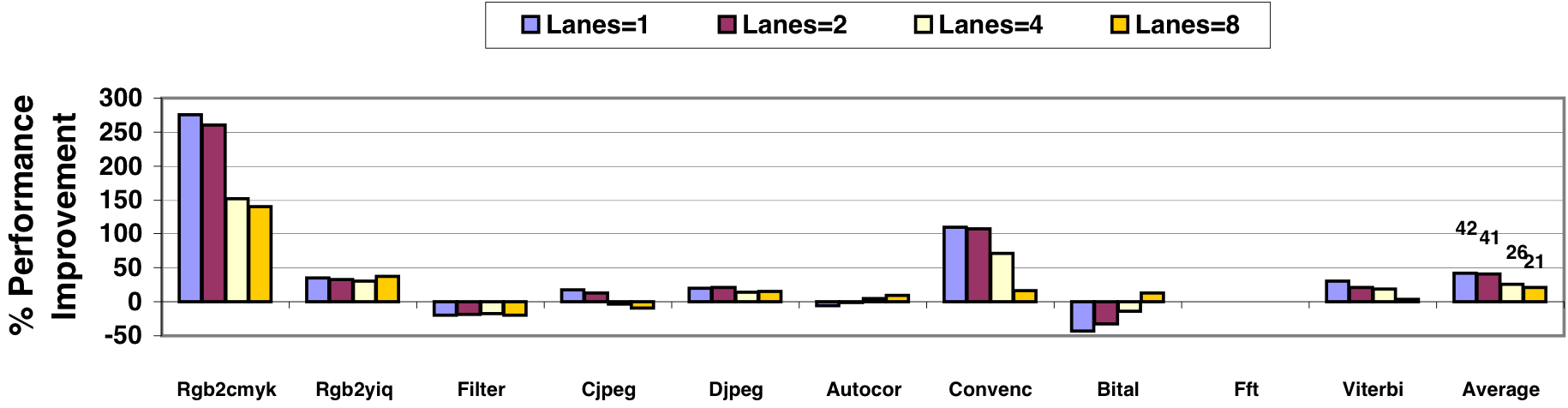

In Figure 5, the performance improvement of CODE over VIRAM is depicted. This baseline comparison assumes both microarchitectures employ the same scalar core, and memory system, and have identical computational capabilities, occupying approximately the same die area. The comparison assumes an equal clock frequency, although the fewer access ports per CLVRF component in CODE allows for a potentially higher frequency than VIRAM.

The results in Figure 5 reveal that VIRAM slightly outperforms CODE in benchmarks with frequent inter-cluster transfers (Filter) or limited opportunities for decoupling across clusters (Bital). However, CODE surpasses VIRAM in most other benchmarks, particularly those with numerous strided accesses causing frequent bank conflicts (Rgb2cmyk). On average, CODE outperforms VIRAM by 21% to 42%, depending on the number of lanes used in each microarchitecture. The consistent performance advantages of CODE are somewhat smaller with 4 or 8 lanes, as a larger number of lanes partially limits CODE’s ability to conceal the latency of communication events.

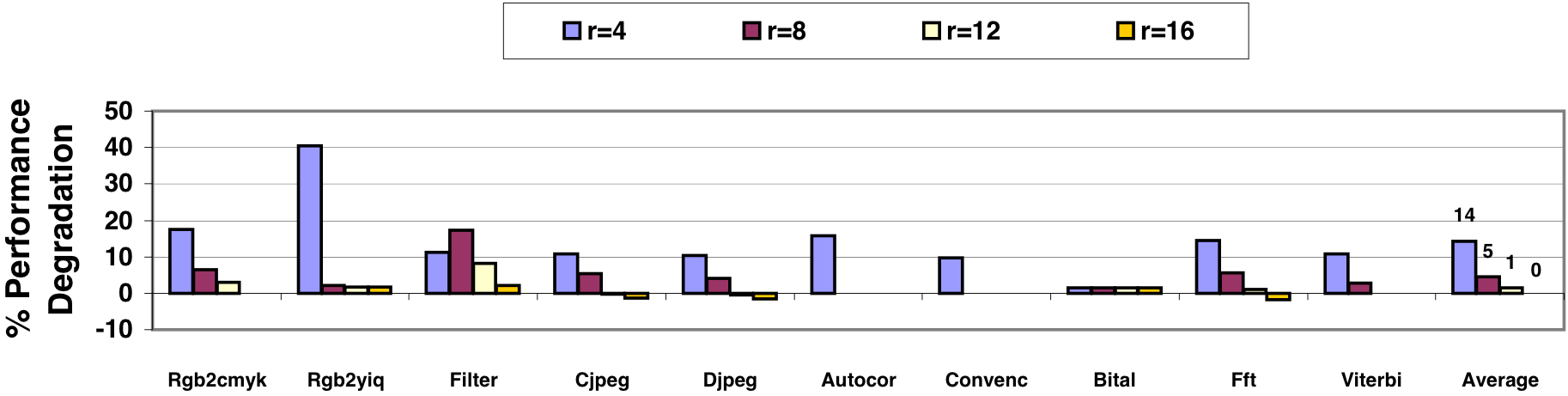

In Figure 6, the performance impact of enabling precise exceptions for vector instructions in the default CODE configuration is presented. The observed performance degradation is attributed to increased pressure on vector registers within each cluster, resulting in stalls in the issue logic.

The VIRAM ISA incorporates mechanisms to minimize exceptions leading to saving/restoring vector registers and reduce the involvement of vector state in each context switch, although their evaluation is beyond the paper’s scope.

Figure 6 indicates that, with 8 registers per cluster, the average performance impact of precise exceptions is less than 5%. Eight local registers adequately accommodate operands, temporary results, and any preserved old values for the VFU in the cluster. With fewer than 8 registers, the pressure on local registers becomes significant, as the VFU requires 2 to 3 vector registers for the operands of the currently executing instruction. In this register-limited scenario, the performance loss can be notable, averaging 15% with a worst-case impact of 40%.

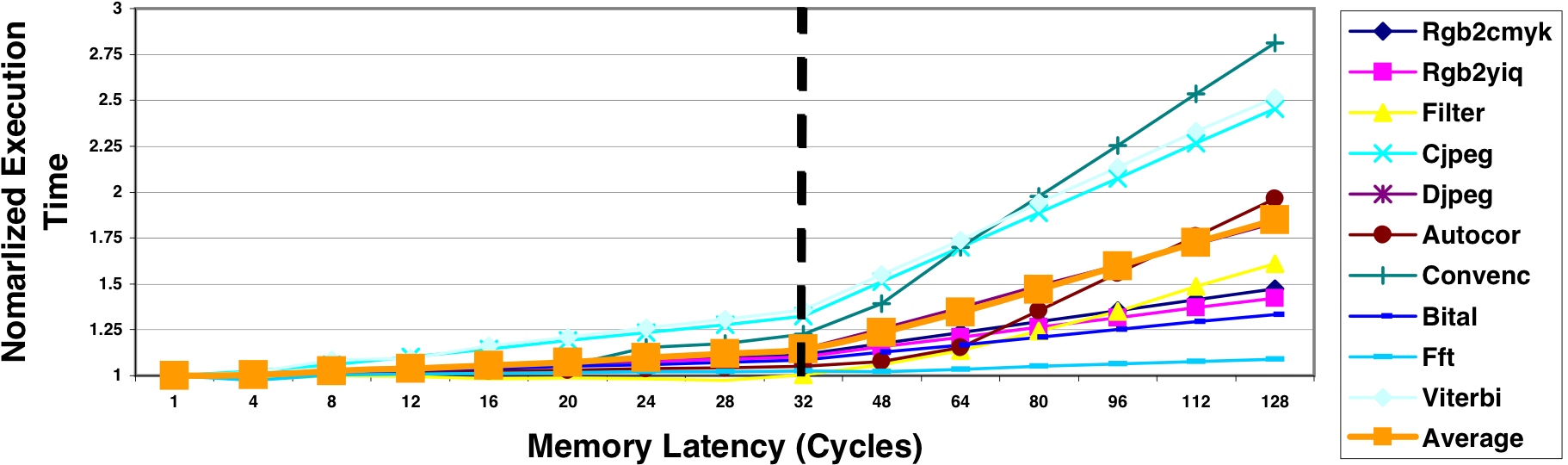

Figure 7 quantifies the combined impact of two latency tolerance techniques in CODE. It illustrates the increase in execution time with rising latency per element access, ranging from 1 to 128 processor cycles. The scenario assumes no limit to outstanding memory requests on either the processor or memory side, representing infinite bandwidth. While practical implementations may impose limits, understanding the maximum potential is insightful. The results indicate that CODE can tolerate latencies up to 32 clock cycles with less than a 25% performance loss compared to the single-cycle access case (perfect memory). At a latency of 128 cycles, the average execution time increases by 1.8 times (worst case 3x). In contrast, the VIRAM processor would experience dramatic performance losses with increasing memory latency due to its rigid pipeline designed for 8-cycle access, unable to tolerate a slower memory system.

Figure 7 also suggests that, with sufficient bandwidth, utilizing an off-chip memory system with a vector processor is reasonable. Despite the associated costs of on-chip and offchip bandwidth, off-chip memory systems can offer increased size and flexibility. A vector processor operating at a moderate clock frequency for power efficiency eliminates the need for on-chip caches or main memory, enabling direct access to an off-chip main memory system with only a minor performance loss.

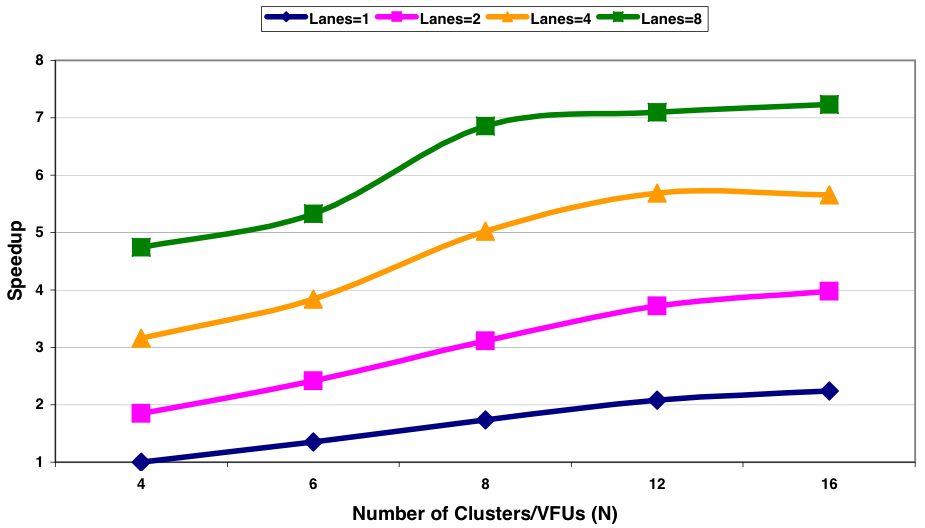

Figure 8 illustrates the performance of CODE as the number of clusters and lanes is varied in the default configuration. The increase in clusters involves introducing additional integer clusters, with an added load-store cluster for every two integer clusters when feasible. To accommodate the extra clusters, the inter-cluster communication network’s bandwidth is enhanced. For 2, 4, or 8 lanes, the inter-cluster transfer width is adjusted to 128, 256, or 512 bits respectively, while properly scaling the ports to the 8-bank main memory system.

Scaling the number of lanes facilitates the execution of multiple data-parallel element operations per cycle for each vector instruction. Two lanes achieve near-perfect speedup of 2, while four and eight lanes yield speedups of 3.1 and 4.8 respectively. Efficiency declines with a larger number of lanes, particularly for programs with short vectors (10 16-bit elements). For longer vectors, multiple lanes reduce the execution time of each vector instruction, making it challenging to mask the overhead of scalar instructions, inter-cluster communication, and memory latency.

Increasing the number of clusters enables parallel execution of multiple vector instructions, resulting in 50% to 75% performance improvement with 8 clusters over the 4 cluster scenario. However, little performance gain is observed with more than 8 clusters due to limitations in efficient use, especially with single-instruction issue, and increased data dependencies and conflicts in the memory system. Combining both scaling techniques allows CODE to achieve a nearly seven-fold performance improvement with 8 clusters and 8 lanes before reaching instruction bandwidth limitations.

Critical Review

Pros

- CODE utilizes decoupled execution, allowing sequences of vector instructions to proceed independently within each cluster. This feature contributes to performance gains by avoiding typical performance degradation asso- ciated with clustered register files.

- The clustered organization of CODE supports scalability with the ability to add more clusters and lanes. This scalability allows CODE to efficiently handle varying workloads and adapt to different application requirements.

- CODE simplifies the implementation of chaining, the vector equivalent of forwarding, across numerous clusters. This is crucial for enhancing the performance of vector processors.

- The clustered organization of CODE is compatible with multi-lane implementations. It allows parallel datapaths within each Vector Functional Unit (VFU) for executing numerous element operations per cycle.

- In performance evaluations, CODE demonstrates advantages over comparable architectures, achieving improved results in various benchmarks, especially those with many strided accesses.

- CODE exhibits tolerance to latency by employing techniques such as decoupling and efficient inter-cluster communication. This enables effective performance even with increased memory access latency.

- Despite the decoupled nature, CODE manages to implement precise exceptions for vector instructions through the effective use of renaming capabilities in the issue logic.

Cons

- While there appears to be an enhancement in performance compared to VIRAM, it’s noticeable that only two benchmarks show significant improvements (Figure 5), while others exhibit only slight enhancements or none at all. This suggests that using an ”average” as the metric in this graph may be incorrect; instead, it should have been the median.

- The cluster selection policy in CODE, aiming to minimize register transfers, may lead to load imbalance. While efforts to consider cluster instruction queue sizes can mitigate this, achieving a perfect balance can be challenging.

- Enabling precise exceptions for vector instructions can introduce additional pressure on vector registers within each cluster, resulting in potential performance degradation and stalls in the issue logic.

- While CODE offers scalability, the efficiency of scaling may decline with a larger number of lanes or clusters. Managing data dependencies and conflicts in the memory system becomes challenging, limiting concurrent instruction execution possibilities.

- While CODE shows tolerance to latency, it still relies on sufficient bandwidth, and achieving optimal performance may require a balance between on-chip and off-chip memory systems.

Takeaways

The CODE microarchitecture presents a novel approach to vector processing, emphasizing decoupled execution for enhanced performance and scalability. By allowing vector instructions to proceed independently within clusters, CODE mitigates performance degradation associated with clustered register files. It demonstrates notable advantages over comparable architectures, particularly in benchmarks with strided accesses, and exhibits tolerance to latency through efficient inter-cluster communication. However, challenges arise with increasing lanes and clusters, including dependency on bandwidth and complexity in exception handling. Load balancing and cluster selection policies are explored to optimize performance, but considerations such as area and power overhead and instruction bandwidth limitations remain significant. Overall, while CODE shows promise in various benchmarks, further investigation is needed to address scalability challenges and optimize exception-handling complexity.

References

- C. Kozyrakis and D. Patterson, “Overcoming the limitations of conventional vector processors,” in 30th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2003. Proceedings., 2003, pp. 399–409.